Bill Carrothers piano

Vincent Courtois cello

Eric Séva baritone saxophone on tracks 6 and 7

Recording, mixing, and mastering at Studios La Buissonne, Pernes-les-Fontaines, France

Recorded May 21 and mixed June 21, 2021, by Gérard de Haro, assisted by Matteo Fontaine

Steinway grand piano tuned by Alain Massonneau

Mastered by Nicolas Baillard

Produced and directed by Gérard de Haro & RJAL for La Buissonne Label

Release date: November 12, 2021

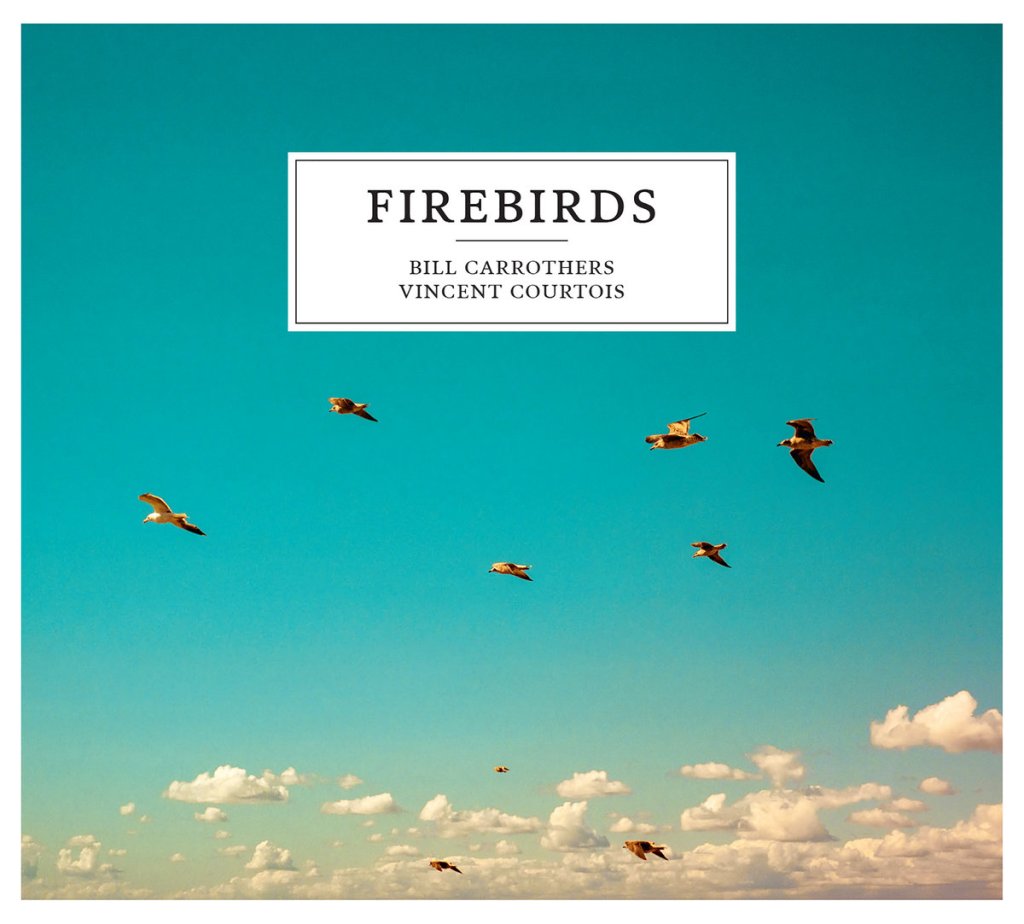

Firebirds is many things, but above all, an act of faith. Gérard de Haro, long a quiet architect of improbable encounters in his La Buissonne studio, had carried within him the intuition that pianist Bill Carrothers and cellist Vincent Courtois belonged in the same current. Each had left an imprint on the room’s air in separate sessions, as if their sounds were tributaries waiting for confluence. Yet they had never tested the tensile strength of their voices against one another. Courtois has confessed that without de Haro’s conviction, the meeting might have remained hypothetical. Trust became the catalyst. Trust in the ear behind the glass, trust in the unseen geometry of chance. What followed feels less like a collaboration than a tide answering the pull of a distant moon.

Indeed, despite the album’s title, it is water that courses through it by temperament. The frame is Egberto Gismonti’s “Aqua y Vinho,” placed at the threshold and the farewell. The cello begins alone, tracing the melody as though drafting a map across an empty sea. Its lines appear rectilinear at first, crystalline and deliberate, then soften, bending into arcs that suggest eddies and hidden inlets. When the piano joins, it does not so much accompany as set the shoreline in motion. Its chords fall with the measured cadence of footsteps along wet sand, insistent yet patient. Courtois responds with widening spirals of sound, ascending in vaporous abstraction before returning, each time altered, to the melody’s wellspring. The repetition never repeats. It accumulates.

The improvised title track arrived first in the studio, though it appears later in sequence, as if the musicians wished to let it steep before offering it whole. The title track smolders with a folk-inflected sorrow, embers glowing beneath a veil of restraint. Carrothers coaxes from the piano a warmth that suggests hearthlight flickering on stone walls. Courtois answers with phrases that hover between lament and lullaby, a bowed murmur that seems to remember something older than language. Their interplay suggests two elements seeking equilibrium, flame reflected on water, each transfiguring the other’s hue.

Standards such as “Deep Night” and “Isfahan” are treated as living aquifers. “Isfahan” opens into a spacious dusk, the arrival of guest musician Eric Séva’s baritone saxophone deepening the horizon. His tone spreads like ink in water, dark yet translucent, amplifying the nocturnal hush that permeates the record. The trio does not crowd the melody; they breathe around it, allowing space to function as tidepool and threshold. “Deep Night” shimmers with restraint, its contours revealed slowly, as if the musicians were polishing a stone discovered at low tide.

Even Joni Mitchell’s “The Circle Game” undergoes a gentle metamorphosis. Pizzicato cello skips like pebbles across a pond while the piano lays down chords that ripple outward in concentric rings. The familiar refrain acquires a different gravity here, less nostalgic than reflective, as though time were not a wheel but a river whose surface records every passing cloud.

The original compositions widen the estuary. “Colleville-sur-Mer” unfolds in a hush that feels tidal, grief receding and returning with unbidden regularity. “San Andrea” keens with a salt-etched intensity, its phrases cresting in plaintive arcs. “The Icebird” introduces a glacial clarity, tones refracted as if through frozen air, while “1852 mètres plus tard” paints in gradients of altitude and atmosphere, suggesting ascent through thinning light. Throughout, de Haro’s production captures not only the notes but the air between them, that charged interval where sound prepares to become something else.

To speak of transfiguration here is not mere embellishment. The album enacts it. Themes dissolve and reassemble, melodies shift from solid ground to liquid shimmer, textures ignite and cool. Each musician remains unmistakably himself, yet the encounter alters their outlines. The music seems to ask whether identity is ever fixed or always in the process of becoming, shaped by the streams it consents to enter. Perhaps art works similarly, eroding certainty, polishing rough edges, carving new channels in the bedrock of perception. If so, the true transfiguration may occur not within the notes themselves but within the listener, who steps into those same streams and discovers, upon emerging, that the shoreline has shifted.