Dominique Ané voice, guitars

Sebastien Boisseau double bass

Stephan Oliva piano, Würlitzer

Sacha Toorop drums

Jean-François Mondot texts

Recorded June 26-30, 2023 at La Buissonne Studios by Gérard de Haro, assisted by Matteo Fontaine and Nina Galuzet

Mixed August 2023 by Gérard de Haro

Mastered at La Buissonne Studios by Nicolas Baillard

Steinway preparation and tuning by Sylvain Charles

Produced by Gérard de Haro & RJAL for La Buissonne

Executive produced by Sylvie de Haro

Courtesy of Cinq 7 / Wagram Music

Release date: February 14, 2024

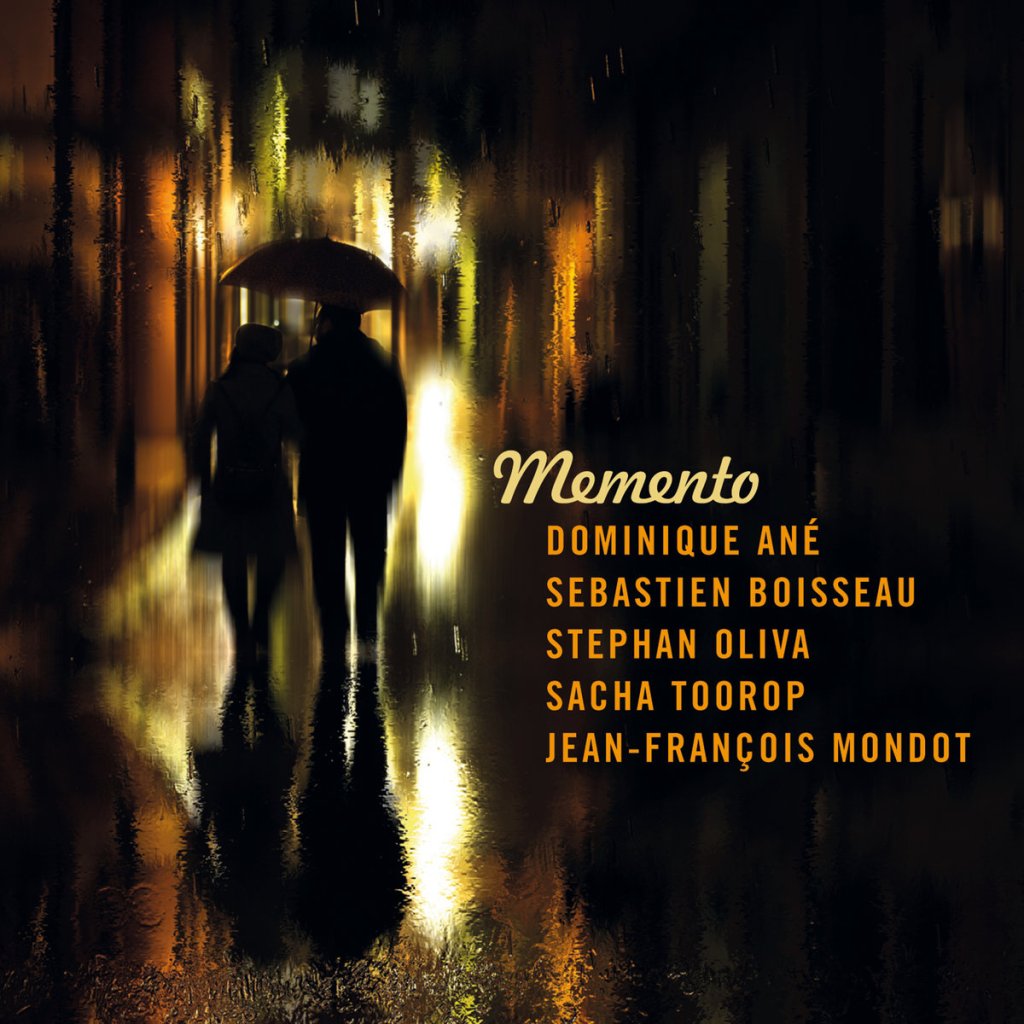

Somewhere between a memory and a melody, this record begins in fog. Not the kind that rolls over a harbor at dawn, but the drifting veil that inhabits the pages of Patrick Modiano, where names distort, streets echo, and time feels less like a line than a dim corridor of half-open doors.

For half a century, Modiano has written variations on the same haunted question: Who were we in the hours that history forgot to record? His novels circle Paris like a compass needle trembling over buried metal. Addresses return. Cafés reappear under new light. A stranger glimpsed on page 20 resurfaces decades later under another name. The past rarely reveals itself directly. It glimmers through rumor, faded notebooks, police files, and the peculiar climate of recollection. In this world, identity resembles a reflection seen in a darkened shop window. One recognizes the shape yet doubts the certainty of the face.

Journalist and jazz critic Jean-François Mondot wandered those corridors for years as a reader. During the strange quiet of the spring of 2020, he attempted something improbable. He asked whether the atmosphere of those novels could be translated into song. Mondot returned to Modiano’s books as though retracing forgotten footsteps through familiar arrondissements. He reread them all, allowing their slow emotional climate to settle around him. From this immersion emerged 13 songs, fragile constellations loosely orbiting the writer’s universe.

The resulting record gradually sketches the arc of a life. A figure appears at its center, elusive and gently refracted. At times he resembles Modiano himself. At other moments he feels closer to the wanderers who drift through the author’s fiction, those solitary witnesses carrying fragments of other people’s stories like loose photographs in their pockets. We follow him through decades as if walking a few steps behind along a damp Parisian sidewalk. First comes the young man, hunched over a notebook in a smoky café where the light seems permanently filtered through nicotine and rain. Later we encounter the lover moving through improbable romances beneath the pale streetlights of the 1960s, a decade that promised freedom yet often delivered only more complicated forms of absence. The years continue their quiet procession. Memory grows fuzzy. Certain streets feel familiar although their names refuse to return. The songs resemble recollections rather than chapters, fragments recovered somewhere between dream and autobiography.

Mondot eventually entrusted these spectral lyrics to Dominique Ané. His voice, flexible and intimate, carries a quality of inward light. Chance played its quiet hand here as well: Ané happens to be a devoted reader of Modiano. And so, the invitation arrived less like a commission than a secret recognition between fellow travelers. Around him gathered musicians whose sensibility gravitates toward the fertile border between silence and sound. Pianist Stephan Oliva and double bassist Sébastien Boisseau bring a subtle gravity to every phrase. Their playing feels conversational, almost confidential. Percussionist Sacha Toorop adds textures that shift shape like clouds moving across a city. The recording itself was guided by Gérard de Haro, whose reputation among musicians rests on an almost mythic sensitivity to tone.

They met at the secluded La Buissonne Studios near Carpentras, a place that seems slightly removed from chronological time. Days passed quietly there while the outside world continued its restless noise. The four musicians recorded the songs live in only a handful of sessions. Breath, wood, and strings carried the fragile architecture of the texts. No attempt was made to polish away the living grain of the performance. One hears fingers on keys, the faint vibration of bass strings, the small hesitations that give language its humanity. What emerges is something rare.

After a brief overture the listener encounters the luminous lift of “Tabarin 1942.” Its gentle ascent joins seamlessly with “Épais brouillard,” together forming a portrait of the artist as a young man who does not yet understand the labyrinth he is entering. These early moments carry a quiet optimism, the sense that the city might still reveal itself. Such brightness proves fleeting. The album soon turns toward more ambiguous territory, presenting Modiano not as a solitary genius but as a voice among voices, often unsure how he will be heard or misheard. In the plaintive “Au pensionnat,” the past presses close like cold glass against the skin. “Café de l’oubli” offers a strangely comforting atmosphere of description, as though certain places exist mainly to shelter forgotten conversations.

Sound design deepens the emotional field without ever overwhelming the words. Ambient touches in songs such as “Fugues” widen the space around the voice. Delicate phrases drift outward like signals sent into the night. One senses that these sonic environments are not decorative additions but spiritual extensions of the narrative. Particularly haunting is the David Lynch-like guitar that haunts “Paris Sixties.” It introduces a shadow beneath the song’s surface celebration of free love. Beneath the dancing silhouettes lies another story, one about disappearance and the quiet corrosion of memory.

Elsewhere the music reveals new facets of the unfolding polyhedron. The arpeggio-laced textures of “Passy 15-20” create a feeling of hesitant movement through unfamiliar districts. “Prières à un bombardier saoul” carries a deeper resonance, its mood suggesting both confession and distant thunder. By the time we reach “La jeune fille à l’étoile,” the voice has adopted a fatigued half-singing that belongs unmistakably to later years. The song seems to lean toward twilight. Every word arrives as if carried across a wide interior distance. Finally comes “Rêve d’Italie,” where the record settles into a luminous elsewhere. It resembles the dream of a coastline glimpsed after a long journey through inland mist. The burdens of life remain somewhere behind the horizon.

Four instrumental interludes anchor the album’s emotional breathing. The balladic piano blues of “Passage des fantômes” opens a corridor through which absent figures seem to pass. “Lignes de fuite” offers a bass solo of quiet beauty. These moments suspend narrative gravity for a time. One hears the spaciousness that Modiano often evokes between paragraphs. Life pauses there. A person may rest inside that pause before continuing onward.

Within the broader landscape of Modiano’s work this project occupies an intriguing position. His novels already possess a musical quality. Translating that rhythm into song reveals another layer of the author’s imagination. The melodies do not illustrate the books. They echo their emotional climate, the sensation of moving through time with incomplete maps.

Listening to this album can feel like wandering through Paris at an hour when the city belongs mostly to ghosts and insomniacs. Streetlights hover above the pavement like small private moons. Somewhere a taxi passes. A café chair scrapes against stone. One realizes that the past has not vanished. It simply occupies another frequency, waiting for the right voice to tune the dial.

Perhaps that is what poetry in song ultimately attempts. It does not reconstruct history with perfect accuracy. Instead, it creates a space where the lost may briefly speak again. A melody touches a sentence. A voice passes through the air. Something forgotten stirs.

Every life leaves behind a constellation of unfinished phrases. Some drift into books. Some hide inside songs. Others remain suspended in silence, awaiting the patience of someone who will listen closely enough to hear what memory itself is trying to say.