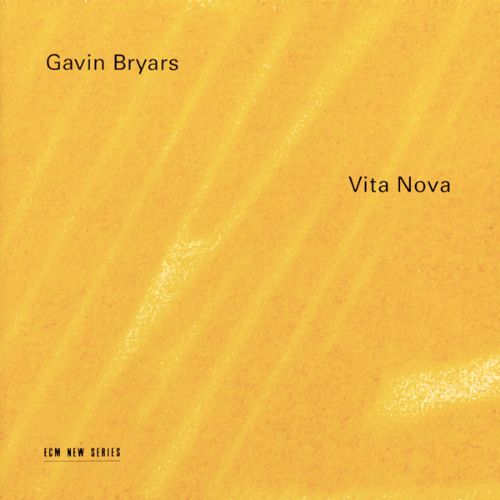

Gavin Bryars

Vita Nova

David James countertenor

Annemarie Dreyer violin

Ulrike Lachner viola

Rebecca Firth cello

The Hilliard Ensemble

Gavin Bryars Ensemble

Recorded September 1993 at Propstei St. Gerold and CTS Studios (London)

Engineers: Peter Laenger and Chris Ekers

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Nomina sunt consequentia rerum.

(Names are the consequences of things.)

–Dante

The music of Gavin Bryars has always been a revelation in my life, and it all began with this 1994 album. In my opinion still one of ECM’s finest New Series releases, Vita Nova is the perfect introduction to the composer’s heartfelt musical cosmos.

Incipit Vita Nova (1989), for male alto and string trio, sets the short Latin phrases that appear in Dante’s otherwise Italian La Vita Nuova. The title means “A new life is beginning” and the piece was written to celebrate the birth of a child, aptly named Vita, to his close friends. That this “new life” was the inspiration for a piece on that very subject imbues the music with the mystery of creation. Its etherealness cannot be overstated, and anyone who adores the voice of David James may find no better showcase for it. The piece swells into audible existence, bobbing like a petal on water that stays in place as waves roll beneath it. From these languid beginnings James ravels into his own life as the strings apply a more pronounced rhythm, each weaving through the others with the deftness of divine messengers. James negotiates the text with a practiced throat, though every instrument has its moment, the cello navigating the words “Omnis vita est immortalis” (All life is immortal) like a thread through a needle. There is an airy pause before the opening motif returns, this time in descending half steps, forging microtonal harmonies between voice and violin.

Glorious Hill (1988) was the result of a Hilliard Ensemble commission. The text is from Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man and imagines a dialogue between God and Adam. Here, Adam is graced rather than cursed with self-awareness—the sacred gift of personal re-creation given to no other creatures in God’s domain, where free will becomes the determinant of human nature. It is a breathtaking piece, and one in which James also figures vividly at the center of a veritable tapestry of choral sounds. But where in Incipit the strings supplemented James with “vocal” gestures, here those gestures are explicitly taken up by the human body, which renders notes with even more fragility. James spreads the text over this choral backdrop in a veneer of supplication as the tenors weave a central drone. Voice-pairs and solos emerge in turns, shifting weight with richly varied effects. Consequently, each section of text seems to be treated as its own full composition. Some are antiphonal, while others are densely polyphonic. The beautiful call of “O Adam” goes straight to the heart, upon which the tenors launch into sustained undulations, even as James charts the most inspiring regions of his unparalleled craft. Gordon Jones provides a few glorious moments of his own. This masterful piece is by far one of Bryars’s finest and ends in shining resolution, folding ever inward into solemnity.

Four Elements (1990) redirects our attention with a larger instrumental ensemble. Scored as incidental music for a ballet by Lucinda Childs, the piece characterizes Water, Earth, Air, and Fire through a variety of tonal and rhythmic combinations (one has to take such pieces with a grain of salt, for the ways in which one views primary elements differs with subjective experience). “Water” opens with an ominous thud and is dominated by bass clarinet and bells, making for a nocturnal, oceanic sound that betrays only the slightest indications of coastline through the fog. Swells of marimba and piano plow the darkness of “Earth.” The pace accelerates in “Air” with a healthy dose of brass, of which alto sax provides much of the melodic thrust before fading into the fluegelhorn-led “Fire,” ending with a slow reverberant finish as James intones a delicate flame.

Sub Rosa (1986) is another ensemble piece, if of a far more intimate persuasion. Dedicated to Bill Frisell, whose track “Throughout” from the ECM album In Line Bryars has re-imagined here, the piece is otherworldly. The central presence of a recorder lends it an antiquated flair and further enhances its enigmatic title. This is perhaps the most pensive piece on the album and speaks of a mind that is spiritually in tune with its own goals and means of achieving them. Beautifully ascendant passages from the violin are overlaid with alluring swaths of recorder, at times struggling against the most delicate of dissonances. The piano marks its path steadily and slowly with triadic arpeggios. Intriguing doublings and an ascendant chord progression make Sub Rosa all the more transitory in its beauty. It skirts the line between waking and dreaming, placing careful steps in a realm where the spirit speaks more fluently than the lips.

Anyone who finds fulfillment in the music of such ECM-represented composers as Arvo Pärt, Giya Kancheli, and Alexander Knaifel should feel rather comfortable being surrounded by this most august music. Bryars is a discovery to be cherished. Listen and be moved.

<< Peter Erskine Trio: Time Being (ECM 1532)

>> John Surman Quartet: Stranger Than Fiction (ECM 1534)