To think of vision as truth is to confuse perception with revelation. Every image born of pigment, photon, and pixel is already a technological interpretation (the #unfiltered hashtag is a lie). Artificial intelligence magnifies the primordial compulsion to externalize thought into form, mirroring our metaphysical anxieties in the intricacies of ocular logic. Yet when AI begins to dream, no longer are we the authors of representation but the represented. Instead of marveling at the shadows in Plato’s proverbial cave, we become the shadows themselves. Artist Trevor Paglen has turned this reversal into both method and critique, exposing a precarious ontology of vision.

In practical terms, AI is fundamentally trained to recognize faces, objects, and places with mundane equivalents. Paglen, however, decided to do something different by feeding AI “irrational” subjects like philosophy, history, and literature. Using a generative adversarial network (GAN), an AI model that creates images based on what it has analyzed and absorbed from existing datasets or “corpuses,” he wondered what might happen when AI hallucinates an image. As Paglen explains, the process involves two networks engaged in a kind of aesthetic duel: a “Generator,” which draws pictures, and a “Discriminator,” which evaluates them. The two AIs play a game of deception and refinement, cycling through thousands or even millions of iterations until the Generator produces images capable of fooling the Discriminator. The results of this strange symbiosis are entirely synthetic images with no real-world referent, yet both AIs believe them to be genuine.

Here, Paglen discusses the project in more detail:

The fruit of these efforts is Adversarially Evolved Hallucinations, an ongoing series begun in 2017 and documented in this book of the same name. Published by Sternberg Press as Volume 4 of the Research/Practice series, it features a conversation between Paglen and editor Anthony Downey, preceded by Downey’s essay, “The Return of the Uncanny: Artificial Intelligence and Estranged Futures.” Downey reminds us that because AI lacks embodied experience, it produces only “disquieting allegories of our world” at best. Its outputs expose the opaque workings of machine cognition, parallel to the brain’s own trial-and-error rehearsals toward getting something “right.” Here, the fourth wall is not merely broken but rebuilt in its own image. Downey asks whether AI is training us to see the world machinically, and whether we already do. Thus, Paglen’s series explores how machine learning “functions as a computational means to produce knowledge” and, in doing so, outs AI as a heuristic device, “capable, that is, of making sense of, if not predefining, how we perceive the world.”

Paglen draws on taxonomies of knowing akin to metaphorical or substitutive instruments of perception. His parameters constitute a cyclical echo chamber that nonetheless manages to step outside the bounds of acceptability while keeping one foot within them. He calls this “machine realism” because the images are recursive of the engine’s own hallucinations. As Downey observes, “the process is never totally predictable, nor is it reliable.” Then again, is reality itself reliable? Do we not also seek to document, catalog, and amplify that which defies predictability?

Because a GAN’s goal is to generate images that appear categorically relevant while simultaneously deceiving the system, its hallucinations blur distinctions between data and invention. Downey warns that such images, if treated as predictive, can easily become more real than real. For even though they do not exist, these errors and phantasms are not anomalies of image-processing models; they are their very foundation.

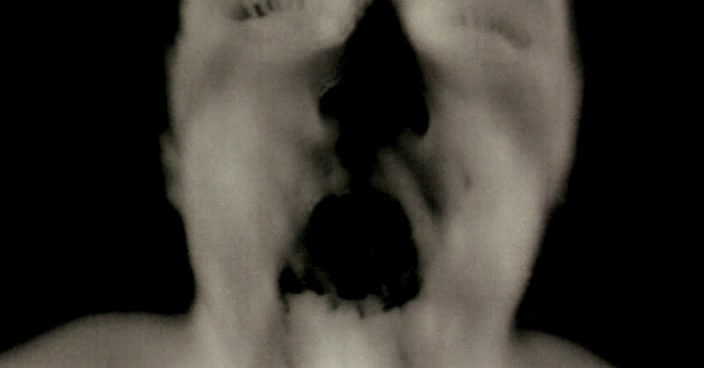

So, what does an AI hallucination look like? Take A Man (Corpus: The Humans):

At first, we recognize a human figure, yet the longer we gaze, the more the image unravels, raising a disquieting question: Is distorting coherence into chaos any different from coaxing coherence out of chaos? Is there a point at which the two converge?

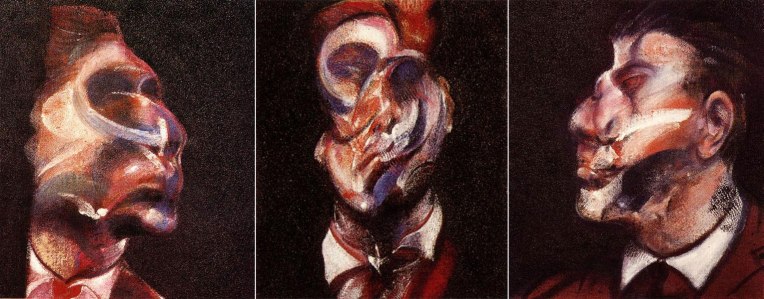

This tension recalls the left panel of Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, where “inaccurate” men accompany flayed carcases:

Despite our aversion to inner flesh, it is the men, those still tenuously tethered to outward form, who disturb us most. When reduced to raw meat, we are more easily abstracted and dismissed; when nearing coherence, we ache for completion.

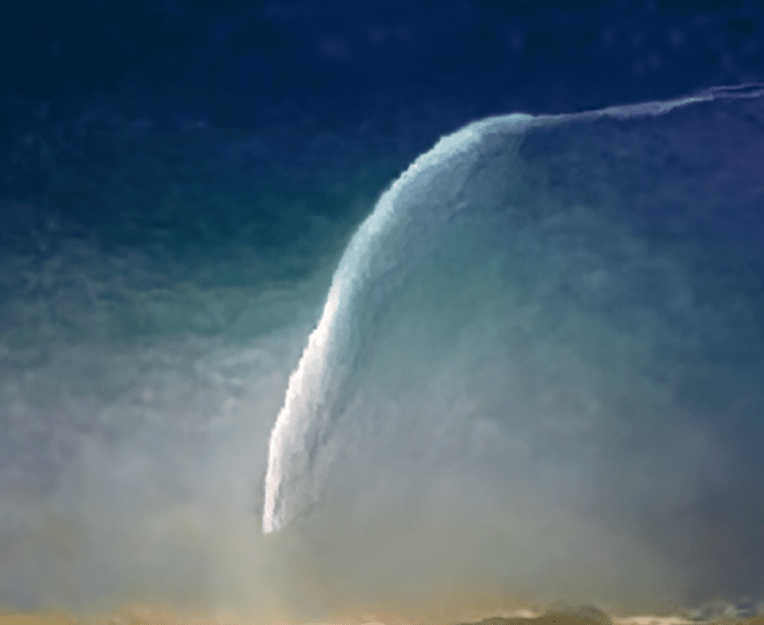

It is perhaps inevitable, then, that Paglen would venture into the supernatural. Angel (Corpus: Spheres of Heaven) borrows from Renaissance art but reassembles its tropes in a landscape unmoored from conventional metrics:

The context is blatantly parasitic, tugging at the figure with distillational aggression. Here, the “angel” is no divine messenger but an ambassador of categorial confusion.

The closer we get to the intimate, the darker the images become. In Vampire (Corpus: Monsters of Capitalism), the most legible face in the book is also the most “demonic”:

The vampire, parasite of parasites, stands as an agent of eternal torment. A Pale and Puffy Face (Corpus: The Interpretation of Dreams) elicits a similar flicker between attraction and horror that is just human enough to seem alive yet warped enough to feel forged:

Why, one wonders, do these visions feel not only unsettling but somehow sinister?

In anticipation of one possible answer, allow me to return momentarily to Bacon, whose Three Studies of George Dyer are a hallucinatory corpus in their own right:

These falsifications unsettle precisely because they start with a uniquely verifiable identity before marring it beyond recognition. Like a coroner’s report, they document the mutilation of everything we hold stable about the self.

Paglen’s systemic hallucinations similarly engage with another psychological touchpoint in the trauma of seeing and of being seen. Through trauma’s hallucinatory unfolding, bodies and landscapes become intertwined in a web of atrocity, where loss and recovery mirror one another. His images dwell in the rupture between memory and forgetting.

A red thread through all this is the illusion of human control. Something nefarious always seems to pull the strings, an invisible force with its own agenda. Escape is made possible only through an existence maintained at great sacrifice. In this metaphysical tug-of-war, the line between the animating and the animated blurs; embodiment and disembodiment become indistinguishable.

Trauma, in this sense, fantasizes an impossible realization of recall, a form of omniscience forever out of reach. It is “locked away,” awaiting the right (read: wrong) invocation to bring it out in the open. But locked away where? In our will toward self-destruction? And what manifests that will more pervasively (if not perversely) than technology? David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, particularly Part 8, is a cinematic case in point. It reimagines the nuclear detonation of the Trinity Test as the birth of evil, a revisionist study in how atomic tampering channels the uncanny.

Lynch’s Inland Empire breeds like-minded logic when, in a moment of horrifying self-contamination, Laura Dern’s face is assaulted by the overlay of her nemesis, the so-called Phantom:

The film’s tagline, “A Woman in Trouble,” underscores her dissolution: corporeal integrity undone in a space of profound unrest. Similarly, Philippe Grandrieux’s La Vie nouvelle drags its characters through a ravaged Sarajevo, where language disintegrates and bodies seek reconciliation in ruin. The result is rebirth and a scream in which one finds only more broken sutures, anticipated by a terrifying night-vision interlude in which the human visage is excoriated of its sanctity.

Walter Benjamin’s dictum that “film is the first art form capable of demonstrating how matter plays tricks on man” has never been more apt. AI-generated imagery likewise gnaws at the barrier between the natural and the supernatural. Its manifestations of trauma without selfhood render the body a vessel of moral and perceptual violation. Displaced from domesticity, it reflects irresolvable turmoil, and the more autonomy it achieves, the more humanity we scramble to recover. This explains why AI’s creations feel so spectral: we have seen their kind before. The only difference is that, whereas once we regarded them only in the mind’s eye, now they are actualized with excruciating pervasiveness.

The premise that benign technologies might beget horror reveals our lack of control more than it restores harmony. These hybridizations of natural and unnatural law force us to question identity itself, ejecting us from human-centered hierarchies into a dialectic with entropic nature. Even something as simple as Paglen’s Comet (Corpus: Omens and Portents) conjures narratives of missiles and imminent annihilation.

We fear not that “evil was born,” as Grace Zabriskie so artfully intones in Inland Empire, but that it never needed to be born. It simply is. It predates us and will outlive us, feeding on forces that nevertheless make us who we are. And so, AI embodies its own eerie vitality, a dead signifier born from the narcissistic desire to reproduce life and deny death’s power. Its synthetic offspring thrive on replication, nursing at the breast of finitude.

Diving once again into Twin Peaks: The Return, we find faces opening into voids inhabited by unclean spirits, golden orbs, and infinite darkness, each a portal instead of a mirror:

In his dialogue with Downey, Paglen explains that the Adverserially Evolved Hallucinations project lets us see inside the “black box” of image-processing models and think from within them rather than be guided by them. This, he suggests, might help us move beyond the temptations of perception. “AI models,” he notes, “actively perform processes of manipulation; they want you to see something.” That desire is itself hallucinatory, as well as dangerous. Just as ChatGPT can invent a nonexistent citation, generative image models can fabricate surveillance realities indistinguishable from fact. The imposition of the fake upon the real becomes so seamless that we cease to question it.

Once something takes the form of an image, it acquires an aura of inevitability. Like a lyric we can’t imagine written differently, the hallucination becomes fixed. These interdimensional images seduce with the promise of infinite variation yet horrify with their fixation on wrongness. In leaning toward the actual through rudimentary shapes and gestures (what Paglen calls “primitives”), we find that the only truth worth protecting is that which resists us. Such is the paradox at the heart of all AI-generated imagery: the more real it appears, the more counterfeit it becomes.