“Technology is never innocent.”

–Marina Gržinić

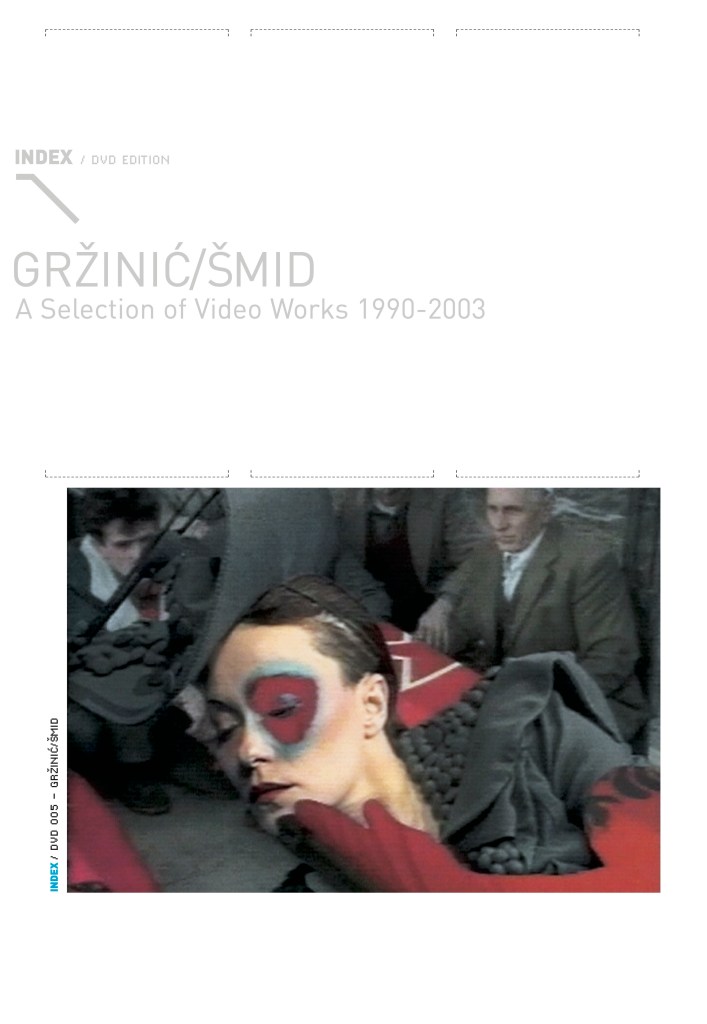

Twin ramparts of Slovenian video art rise to the proverbial occasion in the work of Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, whose decades-long collaboration has forged a visual language rooted in fracture and the unsettled terrain of post-socialist transition. Their films operate as dispatches from the former Yugoslav region, where ideology and memory never truly loosen their grip. The critique that emerges is both intimate and structural. They carve into the spectacle of authority, revealing how power survives by mutating, how it seeps into the body and then disguises itself as habit, nostalgia, or even desire. They scrape away the veneer of official history and rebuild it as a series of contested images. In this state of permanent transition, incrustation becomes their central strategy. One image embeds itself in another as a reminder that trauma never disappears. It simply resurfaces in new forms, as persistent as a scar and as volatile as a suppressed memory. Documentary footage becomes raw material that they melt and reshape into a spectral double, a reminder that truth always has a counterpart produced by the state, the market, or the collective need to forget.

Their 1990 work Bilokacija (Bilocation) embodies this tension by staging a split between body and soul, as if the self has been forced to occupy contradictory geographies. This condition mirrors both the paradox of video and the experience of Kosovo during wartime, a place where identity was carved and recarved by border shifts and nationalist ambitions. Documentary and synthetic images intertwine while Barthes’ reflections on desire are folded into the wreckage of conflict. The result is a meditation on how war reorganizes the self. A black screen compresses itself into visibility as if to suggest that seeing requires force. Images pulsate with the ache of Europe’s unresolved past. A man’s grip on a woman’s arm becomes an aperture into videographic truth, a reminder that even personal gestures become charged when surveillance, ethnic tension, and state control shape the conditions of daily life. A drone of bees fills the soundscape while parades move through the frame. The socialist body appears sculpted by ideology yet undone by its own contradictions. A woman climbs a tower marked “Mengele,” insisting that fascism remains latent beneath the surface of Europe’s democratic self-image.

In Labirint (Labyrinth), also from 1990, the artists summon surrealism not as an aesthetic flourish but as a way to expose the irrational logic that emerges when the aftermath of upheaval becomes the norm. Bosnian refugee camps appear beside theatrical gestures, creating a portrait of a society trying to digest its own collapse. A doctor’s healing hands are powerless against the structural violence embedded in the region’s history. A dying woman’s body becomes an emblem of a ravaged homeland, a reminder that national projects too often run on human expendability. Men inspect a stripper while another peels a membrane from a woman’s body. These actions reveal how patriarchal power thrives in instability. Dancers tremble like historical residue that refuses to settle. The Actionist tremor erupting through their limbs becomes a critique of Europe’s claim to civility, a claim repeatedly contradicted by its own wars, camps, and exclusions.

With 1994’s Luna 10, the stakes widen. The artists draw from the Yugoslav neoavant-gardists yet refract their legacy through the violence of the Bosnian War and the accelerating forces of global technology. Video becomes a lens aimed at the fragmented self of the new world order. A woman lifts a telescope. Diagrams flicker. A shortwave crackles with narratives of conflict described as “radio war,” a term that recalls how states monopolize the airwaves and shape public perception through the management of signals. Domestic labor occurs alongside accounts of cross-border violence, revealing how private ritual becomes entangled with geopolitical strategy. Creativity itself appears as a tool of influence. It can inspire solidarity, but it also constructs hierarchies, invisibilities, and selective empathies. The millennial body is a fearful one because it must navigate a global landscape where production systems act as both oracle and executioner.

By 1995, the montage sharpens into satire. A3 – Apatija, Aids in Antarktika (Apathy, Aids and Antarctica) juxtaposes the wives of Ceaușescu and Milošević with scenes from The Private Life of Mirjane M., exposing how power reproduces itself through domestic performance and the spectacle of femininity under authoritarian rule. A skier moves through Communist iconography. A photographer labors in a darkroom. A body perforated by history attempts everyday chores. Milošević sings into a leek while demons wander through Styrofoam snow. The absurdity is not comedic. It is a critique of how regimes rely on myths, kitsch, and theatricality to mask structural cruelty. The “Ms” dancing in their kitchen, one with a werewolf face, reveal a deeper truth. Systems of authority mutate those who serve them. They turn the mundane into the monstrous and leave no private space untouched.

The 1997 project Postsocializem + Retroavantgardia + IRWIN (Post-socialism + Retro Avantgarde + IRWIN) turns critique into philosophical inquiry. Gržinić frames the discussion while Žižek and Weibel articulate the stakes of avant-garde resistance amid radical restructuring. Žižek argues that the avant-gardist seeks to preserve an ancient core more faithfully than the liberal desire for perpetual fragmentation. This is not a rejection of Enlightenment values but a defense against their appropriation by market forces that claim rationality while enforcing structural inequality. Retro-avant-gardism becomes an act in which reason and action invert themselves. Ideology enters the body only when the body has been damaged. Manifestos appear as shattered fragments because post-socialist reality leaves no space for unbroken narratives. Even Lévi-Strauss’s culinary triangle becomes an allegory in Žižek’s hands. The region’s toilets tell stories about national identity, hygiene, and cultural pride, transforming domestic infrastructure into a commentary on power.

As 1999 crests into frame, the artists widen their lens to all of Europe in O Muhah s Tržnice (On the Flies of the Market Place). The continent appears as a divided brain struggling to reconcile its imperial past with its neoliberal present. An empty swimming pool becomes a metaphor for ideological drainage, a sign that Europe is unsure whether it has shed its history or simply displaced it. Kant hovers as a ghost in the background while communism lingers as residue rather than memory.

Their 2003 work Vzhodna Hiša (The Eastern House) turns domestic space into a battleground of rehearsal. Cinema is reread through Antonioni, Coppola, Siegel, and Badiou while Gržinić’s philosophy threads its way through the narrative. A man sprays a woman with milk from a syringe. At dinner, he mutters slogans that dissolve into frustration. Directorial cues merge with diegesis as if to suggest that civic life itself is staged. Normality fractures while the body’s code is rewritten. A man wakes beside two women who whisper like conspirators. One declares that women and Eastern Europe must no longer be treated as symptoms or mute witnesses. The statement echoes across the film’s terrain of power. Sexuality becomes a site of ideological struggle. References to Alien and Blade Runner reveal a world where love is entangled with biopolitics and fear. Those unaware of their manufactured nature become the ones capable of loving freely because they have not yet internalized the hierarchies that govern them.

Technology appears again as a force that dictates which bodies receive care and which are forgotten. UNICEF enters the frame as a reminder of global humanitarian structures that simultaneously relieve suffering and reinforce social hierarchies. Human activity becomes archival. The cyber-feminist search for identity moves across surfaces where the real and the virtual collide. Gržinić and Šmid show that agency is now mediated by screens that claim objectivity yet reproduce bias at scale.

In the end, they do far more than document history. They anatomize it. They trace its scars, expose its contradictions, and return it to us as a living terrain populated by trembling bodies. Their work insists that understanding the former Yugoslav space demands a confrontation with ideology in its most intimate forms. Desire and power become inseparable. Bodies carry the aftermath of systems that promised liberation yet delivered surveillance, nationalism, and new forms of inequality. Gržinić and Šmid remind us that we live in bilocation. Our bodies remain here while our civic selves drift elsewhere, pulled between the past we inherited and the future we continue to build, often without realizing whose walls we reinforce in the process.