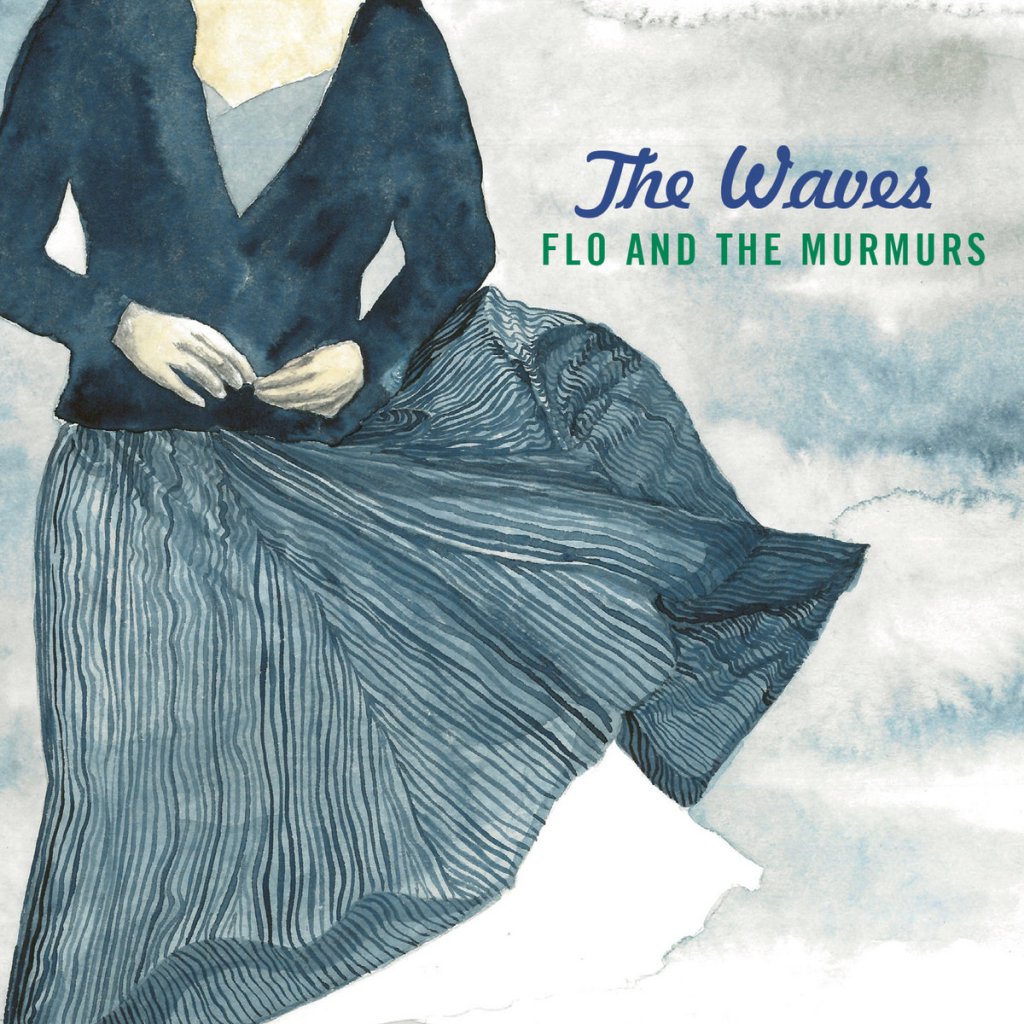

Marie-Florence Burki voice

Sofia de Falco violin

Paula Hsu viola

Bernadette Köbele cello

Snejana Prodanova double bass

Elodie Théry cello (tracks 1, 6, and 11)

Recorded June 1-3, 2023 at La Buissonne Studios by Gérard de Haro, assisted by Matteo Fontaine

Mixed by Gérard de Haro at La Buissonne Studios, June 2023

Mastering at La Buissonne Mastering Studio by Nicolas Baillard

Artistic direction and production by Gérard de Haro & RJAL

and Marie-Florence Burki for La Buissonne

Release date: January 19, 2024

“Like lightning we look but do not soften…”

Somewhere between the breath of a retreating tide and the thin whistle of wind skimming the shoreline it reveals, Flo and the Murmurs begin a quiet migration. At the tip of its vee is the voice of Marie-Flo Burki, lucid yet ghostlike, suspended inside the trembling architecture of an unconventional string quartet. Around her, violin, viola, cello, and double bass open a corridor where experimental folk, contemporary jazz, and chamber music blur into a neoclassical haze. What begins as landscape becomes bloodstream.

Their debut project, The Waves, borrows its language from Virginia Woolf, though the text feels less quoted than carried. Words move through the ensemble like driftwood in a current. Voice and strings travel through the material like figures surrounded by fog. The instruments do not simply accompany the voice. They answer, interrupt, echo, vanish, and return, assembling a shifting mural of fragile light and quiet melancholy. The music feels at once delicate and luminous. To listen to it is to stand at the edge of dusk, where reflection and depth begin to merge.

Flo and the Murmurs formed in 2020, when Burki began exploring the range of color hidden within the string quartet. Hovering above them is The Waves, Woolf’s meditation on time and interior life. Published in 1931, the novel abandons conventional plot in favor of six braided consciousnesses, each speaking in interior soliloquies that ebb and flow. Between their voices, brief interludes describe the sun traveling across the sea from dawn to dusk. The structure shifts between narrative and atmosphere as light moves, darkness returns, and thought follows the same rhythm.

Water saturates Woolf’s imagination well beyond this single work. In The Voyage Out, the sea carries Rachel Vinrace away from England toward the uncertainties of adulthood. To the Lighthouse centers on the restless waters surrounding the Hebrides, where time erodes the Ramsay household with the quiet persistence of salt. Even Mrs Dalloway, rooted in London’s streets and traffic, carries an undertow of maritime imagery. Clarissa remembers waves breaking along the coast of Bourton, while Septimus passes through hallucination like a body in troubled surf. Woolf’s writing often feels musical, as if a score were hidden between her sentences. Flo and the Murmurs bring that submerged rhythm to the surface. What emerges is less a sequence of songs than a tide of sound advancing and receding, carrying narrative through motion over plot.

“The Sea Has Wrinkles” opens with shaded strings over which spoken words drift with intimate calm. Beginning with recitation dunks the listener directly into Woolf’s ocean, where words retain their grain and breath. When Burki begins to sing in “Come,” melody grows naturally from speech, while speech retains the elasticity of song. Violin lines skim its surface while cello and bass deepen the undertow, the viola gliding between them. A phrase appears, eddies, dissolves, and returns altered.

Some of the album’s most striking moments emerge where Woolf’s imagery of transformation takes hold. In “I Am a Stalk,” consciousness slips into vegetal form. The voice lengthens into stillness while the strings stretch into suspended harmonies. Identity briefly moves beyond the human. Woolf often wrote of such dissolutions into grass, wind, wave, or bird, and Flo and the Murmurs approach them with luminous restraint. “I See, I Hear” gathers sensations with mounting urgency while the strings ripple beneath, layering textures of sight and sound. The effect resembles standing waist-deep in surf, currents arriving from several directions. The listener becomes part of the tide.

Elsewhere, the ensemble draws out quiet intensities. “Water” sparkles with pizzicato droplets, each note falling like rain into an unseen basin. “Our Secret Territory” unfolds through fragile harmonic inflections that hover between fullness and absence. Intimacy resembles a hidden cove, beautiful yet uncertain. In “We Are Creators,” the strings gather strength slowly, forming a current that suggests agency and inevitability. “Beauty Set Flowing” carries a similar tension. Its melody lifts gently, though beneath the brightness lies the sense that beauty itself moves through the world like brine through open hands.

Even the instrumental interlude “The Sun Had Risen” continues the narrative. The strings breathe with quiet radiance, echoing the sunrise passages that punctuate Woolf’s novel. Each note glimmers before dissolving into the next. At last, “The Wave Rises” gathers into a final swell. Shadows soften into light until only a pale gray remains, an estuary where distinctions fade. Burki’s voice moves through this closing space with calm acceptance.

Virginia Woolf once wrote that life is not a series of lamps arranged in symmetry but a luminous halo surrounding us from beginning to end. Whereas thought often seeks stable ground, something firm enough to anchor meaning, water suggests another model. It moves constantly, reshapes stone without force, and gathers separate drops into a single body. Woolf understood that consciousness behaves in much the same way. Flo and the Murmurs allow us to hear it.

One leaves the album with a sensation. A quiet drift. A widening horizon within the mind. Somewhere beneath the noise of daily life, the tide continues its patient breathing. Perhaps our thoughts are only small waves, rising briefly within that immeasurable sea of voices.