“The cinema of Hollywood is a cinema of exclusion, reduction and denial, a cinema of repression. There is always something behind that which is being represented, which was not represented.”

–Martin Arnold

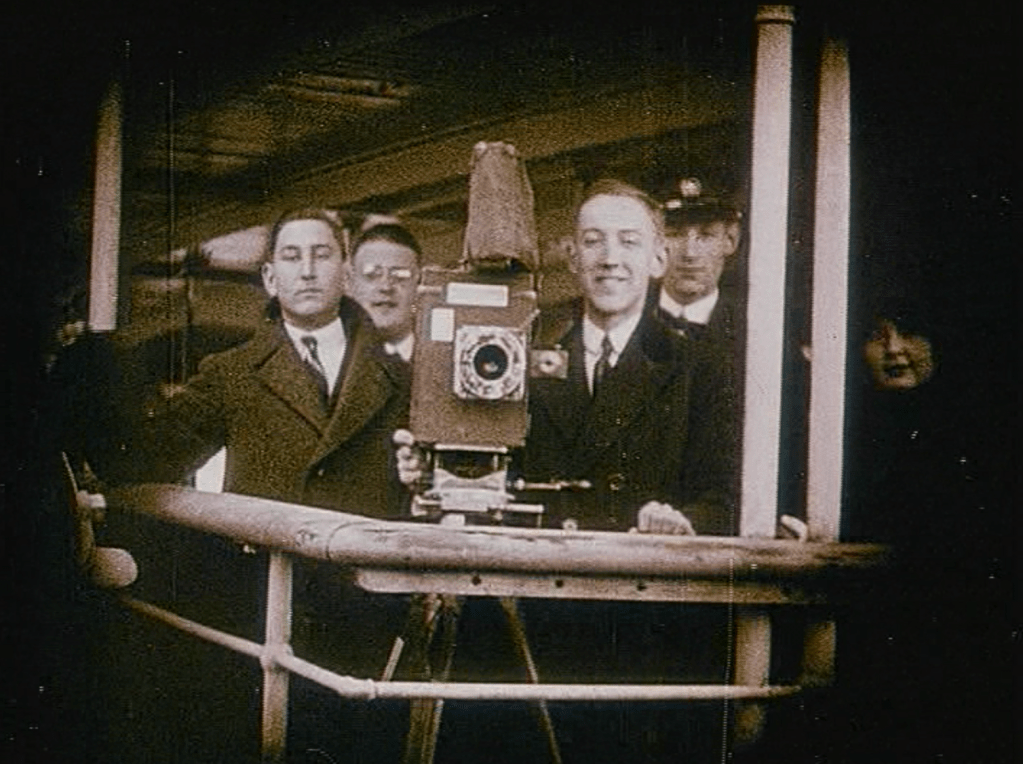

Martin Arnold’s oeuvre grows from a profound distrust of popular narrative machinery. For him, the classical montage is never innocent. It is a device for shaping behavior and disciplining desire, a system that filters the unruly impulses of human life into tidy patterns of sanctioned emotion. His practice revolves around locating this withheld remainder. By tearing apart fragments of studio films and reassembling them through frame-by-frame expansion, reversal, and obsessive repetition, he subjects familiar scenes to what James Leo Cahill terms the “cineseizure,” a state in which the image convulses until its buried drives appear like worms after rain.

Cineseizure is an apt word: a blend of possession and dispossession, mechanical spasm and sexual tremor. Arnold forces films to reveal their unconscious, much as micro-expressions betray horror, disgust, and perversion. Gestures that once passed unnoticed begin to twitch with emotional residue. The screen becomes a site where the smallest flicker of a hand or tightening of a jaw turns into a phonograph needle tracing grooves of repressed histories. In these manipulated spaces, time no longer flows.

Arnold’s reworkings are the truth serum of cinema. They expose repetition as the motor of the medium and repression as its silent engineer. What emerges is not merely a riff on form but the exhumation of realities as much cut out of the sovereign frame as embedded within it.

The trilogy that anchors this experiment reveals how a few seconds of onscreen time contain entire worlds of unspoken (hyper)tension. Arnold extracts domestic interiors, Oedipal line crossings, and adolescent longings, then stretches them into dense diagrams of psychic movement. Gender, childhood, sexuality, and authority become patterns of muscular recurrence. The screen no longer shows bodies acting but bodies being acted upon.

The first of these excavations, pièce touchée (1989), begins with an ostensibly brief moment from Joseph M. Newman’s The Human Jungle and magnifies it into fifteen minutes of convulsive intimacy (if not intimate convulsion). A man attempts to enter his home, while a woman sits reading in the living room. In Hollywood’s fantasy, this is the ideal daily ritual, but Arnold transforms it into a scene of anxious reiteration that strains against its own script. The woman cannot leave the frame without being snapped back into it. Her fingers twitch with illegible agitation. She opens her mouth as if practicing a line she does not believe. The man cycles through the threshold, an entrance that never quite becomes arrival. Even the hallway light participates, flickering in spasms that mirror the scene’s hormonal uncertainty. Bodies merge with furniture. The room turns in on itself. Thus, home life reveals its nervous skeleton, quivering beneath the surface of flesh rewritten.

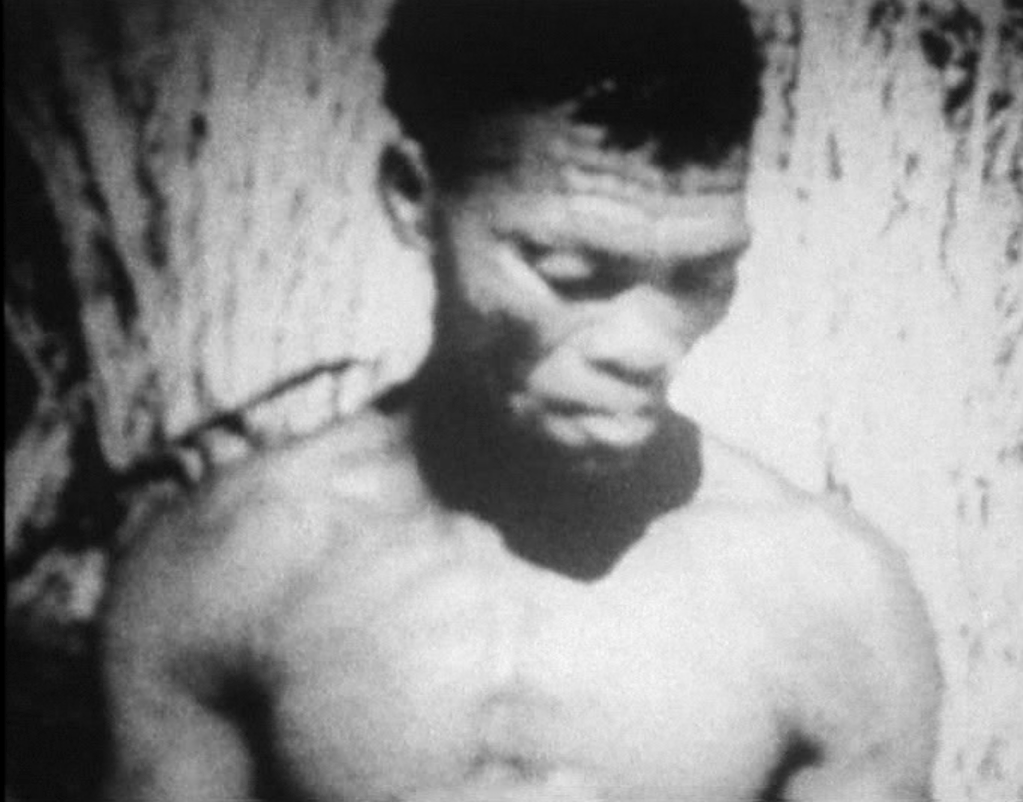

A similar unease shapes passage à l’acte (1993), which dilates a breakfast scene from To Kill a Mockingbird into a study of familial disarray. A 33-second interlude becomes a chamber of hesitation, rebellion, and libidinal undercurrents too complicated to contain. Atticus’s movements take on a compulsive rhythm. His son Jem mirrors him with unnerving precision, as if domesticity were nothing more than a chain of inherited gestures. Scout slams her fork, and the percussive violence of that simple action ripples through the room. Attempts to leave the house collapse into stuttering rounds, caught as the family now is in an emotional weather system they cannot name.

The trilogy culminates in Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy (1998), through which Arnold turns the coming-of-age Hardy musicals inside out. What once passed as innocent family entertainment mutates into a network of taboo signals sublimated into song and cheer. Mickey Rooney’s hand strokes his mother’s arm with a persistence that borders on possession. Her breathing grows expectant, her lips forming impossible Möbius strips. Judy Garland’s singing disintegrates into the repeated sound of “alone,” a cry that becomes a wound, a seduction, and an existential refrain. Even the word “love” fragments, the “v” floating like a detached shard of desire. A paternal slap intrudes repeatedly, failing to dispel the fantasy it aims to suppress. By the end, circular breathing turns a single note into an inhuman pulse, as if any erotic charge has surpassed the capacity of the body. Mortality and musical spectacle collapse into a haunting indrawn breath.

Bonus works included on the DVD include Don’t – Der Österreichfilm, which lays Kyle McLaughlin’s crying from Blue Velvet over Austrian footage with a mood that makes cultural memory feel irradiated from within, while Jesus Walking on Screen, with its repeated plea for sight over blackness, distills a hunger for revelation into a single gesture. A miniature trailer for Kunstraum Remise transforms a train’s approach into a slow ignition of desire, while a Viennale spot built from Psycho wrests terror from a scream that refuses to resolve as the shower continues its incessant spray on loop.

Taken together, these works illuminate Arnold’s true concern: not the films he manipulates but the psychic conditions they mask. By destabilizing the flow of time, he allows gestures to confess what the plot once denied. The repression that once held Hollywood in place becomes visible as a trembling scaffold. In Arnold’s hands, film reveals the desires it tried to silence, the violences it displaced, the fears it dressed in gaudy costumes. Through temporal fracture, he returns the moving image to its buried pulse, showing that it remembers more than it ever intended to reveal and that, even with the right interrogation, it always has more to confess.