My latest review for All About Jazz should be of special interest to ECM fans. The compilation Magic Peterson Sunshine chronicles the history of the German MPS label, a vitally important predecessor to ECM Records on which many familiar artists (including John Taylor, Eberhard Weber, and John Surman) made key appearances. This album is a vital cross-section of music history and belongs on the shelf of anyone who cares about the history of jazz in Europe and beyond. Click the cover to read on!

Author: Tyran Grillo

Kimmo Pohjonen review for RootsWorld

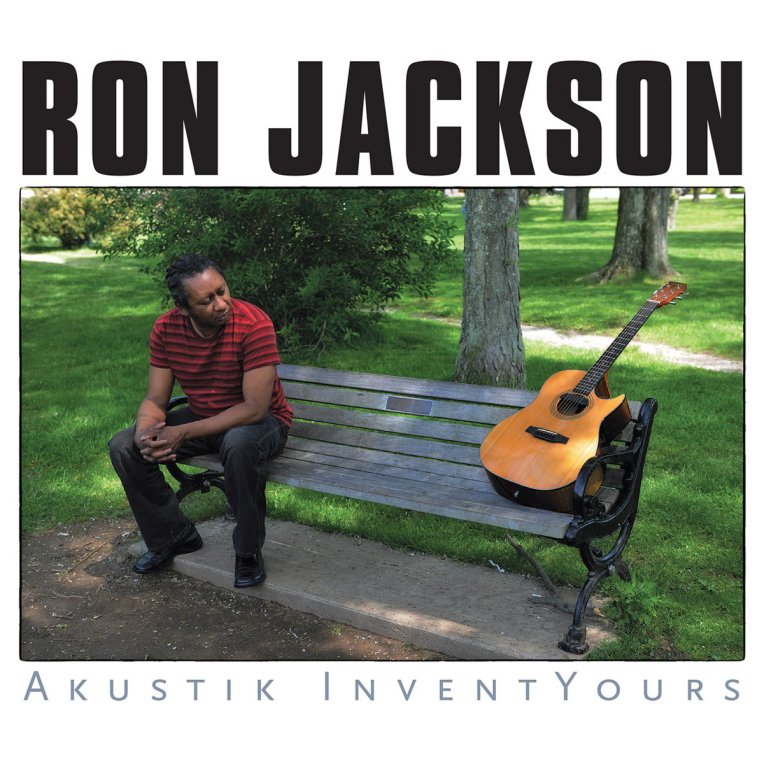

Ron Jackson review for All About Jazz

Lee Scratch Perry: Rise Again

Lee Scratch Perry + Bill Laswell = a collaboration written in eons-old starlight. The pioneering Jamaican producer and shamanistic bassist have been approaching dub from different directions—one from the past, the other from the future—and at last meet in the here and now. Tunde Adebimpe, Gigi Shibabaw, and Hawkman throw their vocal legumes into this vegetarian stew, while Bernie Worrell (keyboards), Peter Apfelbaum (tenor sax and flute), Steven Bernstein (trumpet), Josh Werner (bass), and Hamid Drake (drums) extend their bodies toward an overlapping dimension in which to sing.

As a unit, these musicians render the studio a portal of insight into the human condition, crafting art as an effigy to be burned in offering. Only they can see the glyphs written in every trail of ganja smoke, swirling and separating into runways for alien landings. This revisionist history of life unfolds like a book not only bound in but also written on skin, burnished by hands whose shapes are much unlike our own. Instead of fingers: attracting forces. Instead of wrists: only skies, cocked to the angle of the sun’s passage at any given moment throughout the day. The compass is strong with this one, for its seeking is bound to the realm of the dead, if scrutinized only by the living.

Perry is a griot on stilts. He drops his beats and words from a higher place. In the rain of his exhalation, one feels a lifetime of atmospheres at play. From autobiography and politics to godliness and metaphysics, his themes interlock across vast spatial and temporal expanses, but always in service of the utterance in real time. It all begins in the narrative impulse of “Higher Level.” With animal wanderlust and anti-parasitic skin, Perry charts a course through this world of hunters and sinners, following ley lines along which Rastafarian secrets, scriptural wisdom, and the esotery of personal experience share borders.

In “Scratch Message,” Werner takes a ride in the captain’s chair, navigating this vessel with religious deference. It is a stroll through the valley of life, in which the waters of tolerance have run dry, yet where the footprints of many travelers before have laid a path of resistance. It is this which Perry follows beyond the oceans of his island and straight into the heart of “African Revolution.” This call of arms to rid the world of arms is a protest in the name of salvation. It bows to the same goddess of groove who in “Butterfly” dons a crown of blessings.

Though the peace cultivated by this crowd may be far from the madding others, Perry’s knowledge of the spider’s web runs deep. In both “Wake The Dead” and “E.T.” he gives listeners a private tour of conspiracy, flushing out toxins of ignorance with nutrients of awareness. The latter tune is especially reminiscent of Laswell’s Sacred System project, an early dub transmission from 1996 that still ripples across these waters. Through the governmental sacrament of blood and fire, he sharpens the blade honed by Perry decades before, now polished by millennia of intergalactic breeding and glinting in the bonfire of oppression.

Perry’s refusal to be pinned down by the weight of elitism comes from being supported and pushed ever upward by the hands of his ancestors. And in the songs “Orthodox” and “House Of God,” the former gilded by Shibabaw’s golden throat, he attunes his vibrational frequency to the rhythms of prayer. Laswell’s bass drops head and heart into poetic comportment, as Shibabaw gives her all to the inner science of these readings, singing with the knowledge that stillness is just an illusion resulting from perfect equilibrium between rising and falling.

Turning the kaleidoscope again, Perry shows us his whimsy, rapping through the televisual brilliance of “Dancehall Kung Fu” and spinning the roulette to land finally on “Inakaya (Japanese Food).” On the surface an ode to cuisine but in actuality a blood pact shared between two pricked geographic fingertips, it is an ice cube on the forehead in summer.

If you want to know where dub is heading, you must understand where it has come from. And on Rise Again, we get both in one circle. But let there be no talk of masterpiece, for Perry is a master, whole.

(For more information, click here.)

Last Exit: Iron Path

League-of-his-own guitarist Sonny Sharrock. Subterranean saxophonist Peter Brötzmann. Atmospheric bassist Bill Laswell. Former Albert Ayler drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. Alone, each is a power tower of musical ideation. Together, they blind the sun. In 1988, these free-jazz atoms bonded to unleash their only studio molecule. Now remastered for the 21st century, it bleeds redder than ever.

Like Everyman Band before them or Krakatau after, Last Exit pummels through walls of expectation as if they were made of feathers. From these they fashion a giant pair of wings across 10 spines of reality. As Steve Lake so reverently describes in his liner notes: “There’s no false modesty in Last Exit, no false anything. The group is important precisely because its rush of sound is a heartfelt force. It sweeps away all the fakery that proliferates on both sides of the highbrow/lowbrow cultural divide.” None of that flavor has dulled these last three decades, and if anything has grown more piquant with age.

The most obvious politic at play on the scale of Iron Path is its balancing of opposites. “Prayer” feels like anything but as a growling bass eats into the foreground, one pathos-ridden chew at a time. But as the terminal illness of its build reaches a plateau, bells of immolation toll for those with water. Guitar and drums power through resistance like berserker prospectors panning for untranslated scriptures. And these they find in the proffered wisdom of Brötzmann’s horn, which by virtue of prophecy spews all of its treasures for the taking. So does “Marked For Death” reveal its hidden meanings with patience. Brötzmann’s soloing exemplifies the restraint required to unleash such morbid finality. In “Eye For An Eye,” too, Laswell blows smoke through gritted teeth: a mountain pushed through a chain-link fence, to the call of an interspace chant.

Some tracks are purposefully grounded in the everyday. “The Black Bat,” for instance, bears dedication to Japanese producer Aki Ikuta, who tragically died at the age of 33 as the result of a car accident the year this album was recorded. His restless spirit echoes throughout this piece, in which colors swirl into mournful timbre. Other passages are more obscure and require further peeling of the ears to appreciate. The title track, with its eastern infusions, whispers of simulacra slashed across time, while “Devil’s Rain” finds Sharrock rocking the cinematic edge as Brötzmann lobs the heart of a volcano into the exosphere.

“The Fire Drum” is one of two blatantly descriptive turns, boasting comet streaks of brilliance from the guitarist and reedman. “Sand Dancer,” on the other hand, is Laswell’s electric phoenix all the way. And if these seem too grounded in their spaces, one needn’t worry, as both “Detonator” and “Cut And Run” hybridize aggressive haunts with tidal preaching, until only one piece of advice remains: Structural failures are the birth of monumental impulse.

(For more information, and to hear samples, click here.)

Milford Graves & Bill Laswell: Space/Time Redemption

The first studio duet of drummer Milford Graves and bassist Bill Laswell, both yielding warriors of their respective dark arts, is a selfless proclamation. Residing in their speech is the yin for the other’s yang, a drop of sun for moon.

In approaching this vessel, one does better to go below decks from the first sounding, interpreting this axis from its crux outward. And toward the end, we have that very intersection in the form of “Autopossession.” More than a title, it is a mission statement by which the body is rendered inert through spiritual process. Being a solo from Graves, it melts surrounding ice, stopping just before it reaches steam. Thought and action likewise turn into liquid. But the drummer’s is more than a beat-driven consciousness, for here the specter of regularity serves only as the reminder of a talismanic past. If the head nods at all, it is because the mind has left it behind.

Regressing a level of reality gives us “Eternal Signs,” one of four collaborative improvisations that include “Another Space” and “Another Time.” Each is a ring linked to the others in a multidirectional chain of being. Drums and bass serve as equal partners, connected by lightyears of shared experience. The energy seems violent in origin, even as it breeds nothing but harmony. A pliant strum or forceful tap: either closes the gate as easily as opening it, sealing terror exhaust from the inevitability of inhalation. The more such improvising develops, the more macroscopic it becomes, crumbling outward in an explosion of planetary dimensions. It is the repression of history, demystified in music.

Yet the most willful approach reverberates throughout the dedicatory “Sonny Sharrock,” which like its namesake unwinds the familiar into unexpected filament. Laswell applies an echo effect, allowing it to float above the ionosphere of influence over which his instrument’s dreams wander. Amid gamelan-like touches from Graves, he adds flame upon gnashing flame, so that oxygen expends itself at shaman’s touch. There is a shape to that fire, one that flits between human and animal with the unpredictability of an autumn leaf’s path. Percussive chemicals seep into those four heavy strings, while the drums eject prophecy from the pilot’s seat in favor of crash landings, leaving Laswell’s branch-bending scriptures to flutter alone in the final breeze.

There is no mystery, other than the space to which the album’s title refers. It would seem to be our own by virtue of our listening, organ-less and multiple, a mirror fogged by the breaths of gods too far away to see yet too close not to sense in the shifting of tress at night just before sleep shades your retinas. But on closer inspection the reflection is that of a star child breastfed on shadow, now spitting words of light for our foraging. It returns the gaze and whispers: Wings were not invented for flight, but flight for wings.

(Available at Amazon here.)

Kurt Riley: The Man Who Fell to Earth

Music and life start the same way: as a seed germinating until it is ready for the world. Many have beaten objects for want of rhythm; others have extended their bodies through instrumental prostheses in deference to melody. But the most primal search of the modern age is that of a voice for an amplifier. Ithaca, New York-based singer Kurt Riley is one such seeker, holding a microphone like a newborn whose umbilical cord twirls back into the electric womb where his second album Kismet has been incubating for over a year.

A student among a band of students, Kurt has balanced his academic life at Cornell University with a musical one on another planet, from which his sonic gatherings at last fell into place during his premiere performance on April 29, 2016.

Teaming up with the glam rocker on this interstellar ride were drummer Olivia Dawd, bassist Charlie Fraioli, guitarists David Dillon and Sam Packer, keyboardist Ruth Xing, saxophonist John Mason, and backing vocalist Kristina Camille Sims. The latter added dialectical undercurrents to Riley’s over, balancing dichotomies not only of gender but also temporality and location in the grander context of his outreach.

The band played the entire album from front to back, opening with the instrumental “Eternity,” a synth-heavy blush that plowed through stardust in a procession of songs without words. Wavering before a backdrop of endless galaxy, Kurt and his musicians prepared their earthly transmission with steady hands and fibrillating hearts. Not only was it a portal of insight into the emotional story about to unfold, but also a foreshadowing of hope: a touch of rain amid the brimstone to ease the pain of progress. More importantly, it lent sanctity to the venue, allowing us to forget we were sitting in nothing more than a university auditorium. Between the retro arpeggio, which flushed the audience of its insecurities in a space normally reserved for less intimate instruction, and the slack guitar floating above it all, a cosmos waited to unleash its primal scream.

In their rendition of “Eye of Ra,” the album’s first proper song (at least on human terms), Kurt and his astronauts stared into the face of something sinister and acknowledged lack of escape from that which knows us without sight. Hanging on to a kingdom by its lowest rungs, a realm where hardship is a prerequisite for the course of life, they nevertheless cradled this dire circumstance for what it was: a baseline of realism that allows lowly citizens to remember, in the end, just how far they’ve come beneath untouchable authority.

Like motivations flowed through the follow-up song, “Engines Are Go!” Here the narrative voice was youthful, almost naïve in its gradation from verse to chorus. Kurt pushed these images through the mesh of experience until they were unrecognizable as their former selves. This road trip through the unrequited jungle gave over to “Theft of Fire.” The first incision of an even more romantic surgery, it was a turning of tidal expectations from doom to failure, the key difference being that the latter involves a choice.

The first single off Kismet, “Hush Hush Hush,” provided the most classic sound. Its pianistic backbone flexed to the beat of a retroactive metropolis in anticipation of biting its own tail. As the ballade du jour, it was a singular passage of reflection, projected through a darkly loving lens of yearning. All of which fed into the first push of “Domino,” sending us all through a cavity of falling rocks.

The circularity of “As We Know It” came about through words of material destruction. “Humanity: Why so in love with the end of things?” Kurt sang, blowing his brains out through a harmonica at the end like a catharsis beyond false semantic promises. It was also a turning point in the program, which paled from black to red as the contours of “Whore” came into focus. For this, Kurt was joined by local rapper Asanté Quintana, whose delivery rose like gorge mist through safety netting.

This sea change was further evident in “God’s Back in Action,” a piece of soul for the lonely sharpened to an edge of comfort. It was the very definition of the Kurt Riley experience, which behind the weathered leather and mascara teardrops cradled a motivation of care. As too in the all-reaching “Universe” especially, a Queen-like danse macabre for the soul, true love was never far behind.

And in “Human Race,” which sent balloons flying throughout the auditorium, Kurt pulled that hope into the present. A self-imagining broken into heated breath…

…but nowhere more so than in “Burn It Up,” which gave that hope a vessel in which to soar.

And with that benediction, closed like a fist around slippery assurances, Kurt and his mortal cohort closed up the castle, swept the blood and sweat under the carpet, and tread out into the galactic night with new followers in tow.

Toward the end of his life, David Bowie once characterized himself as a man lost in time, but Kurt is one who is just beginning to find himself in it. Should you wish to know more about his time on Earth, which is sure to breed noteworthy developments, click the album cover below.

See you on the other side.

(Concert photos: Yours Truly)

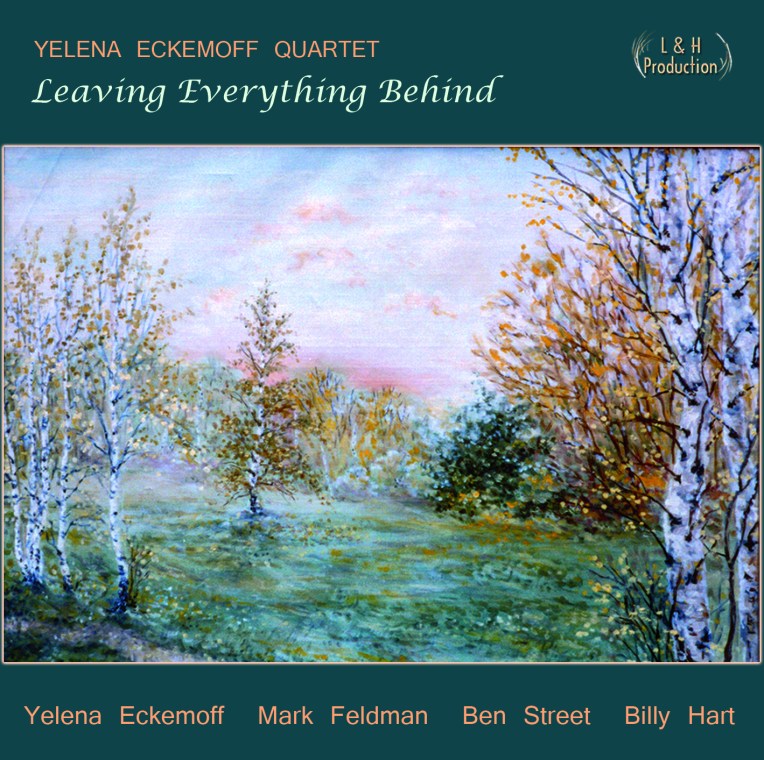

Yelena Eckemoff Quartet review for The NYC Jazz Record

This week marks a new venture for me as a writer for The New York City Jazz Record, for whom my first review appears in the May 2016 issue. Scroll down to read the review. You may also access the entire issue directly in PDF format on the magazine’s website here. The issue also features an article about ECM artist Nik Bärtsch, whose CD release concert for the new album Continuum I will be reviewing for All About Jazz in May.

Since 2006, pianist Yelena Eckemoff has been stirring a chamber jazz cocktail two parts through-composed for each one improvised. With Leaving Everything Behind, she has perfected it. Eckemoff’s road to this point has been paved with classical roots, but has attracted increasingly heavier hitters of jazz to her entourage. Her friendship with bassist Arild Andersen, for one, led to their “Lions” trio with drummer Billy Hart. The latter’s approach to color makes for an easy corollary to Eckemoff’s painterly ways and his retention this time around is felt alongside two new collaborators: violinist Mark Feldman and bassist Ben Street.

Though Eckemoff has always been a self-aware musician, Leaving Everything Behind finds her in an especially conceptual mode. She repurposes earlier compositions among the fresh to tell the story of a young woman fleeing Soviet Russia and the ways in which music has constructed bridges to the places she put behind her. Whether comping with confidence in “Mushroom Rain” or drawing with light in “Hope Lives Eternal,” she moves around her bandmates by means of a genuinely expressive outreach.

The Eckemoff-Hart nexus gives off its broadest spectrum in the more programmatic pieces. Between the raindrop impressions of the “Prologue” to warmth of closer “A Date in Paradise,” pianist and drummer dispel an overcast sky until only sunshine remains. Titles such as “Spots of Light” and “Ocean of Pines” further indicate that silver linings reign supreme.

The balance of distinctly classical arrangements and jazzier change-ups yields affirmative soloing, most effectively through Feldman’s clear and present notecraft, as in the evocative “Coffee and Thunderstorm,” a quintessential embodiment of what unites Eckemoff’s chosen genres: namely, the ability to expand fleeting moments into poetry. Other highlights in this regard—all the more so, ironically enough, for being so darkly ponderous—include the panoramic “Love Train” and, above all, the simpatico title track.

This set of variations on a theme of memory is Eckemoff’s finest to date and may at last put her on a map where she has been largely ignored.