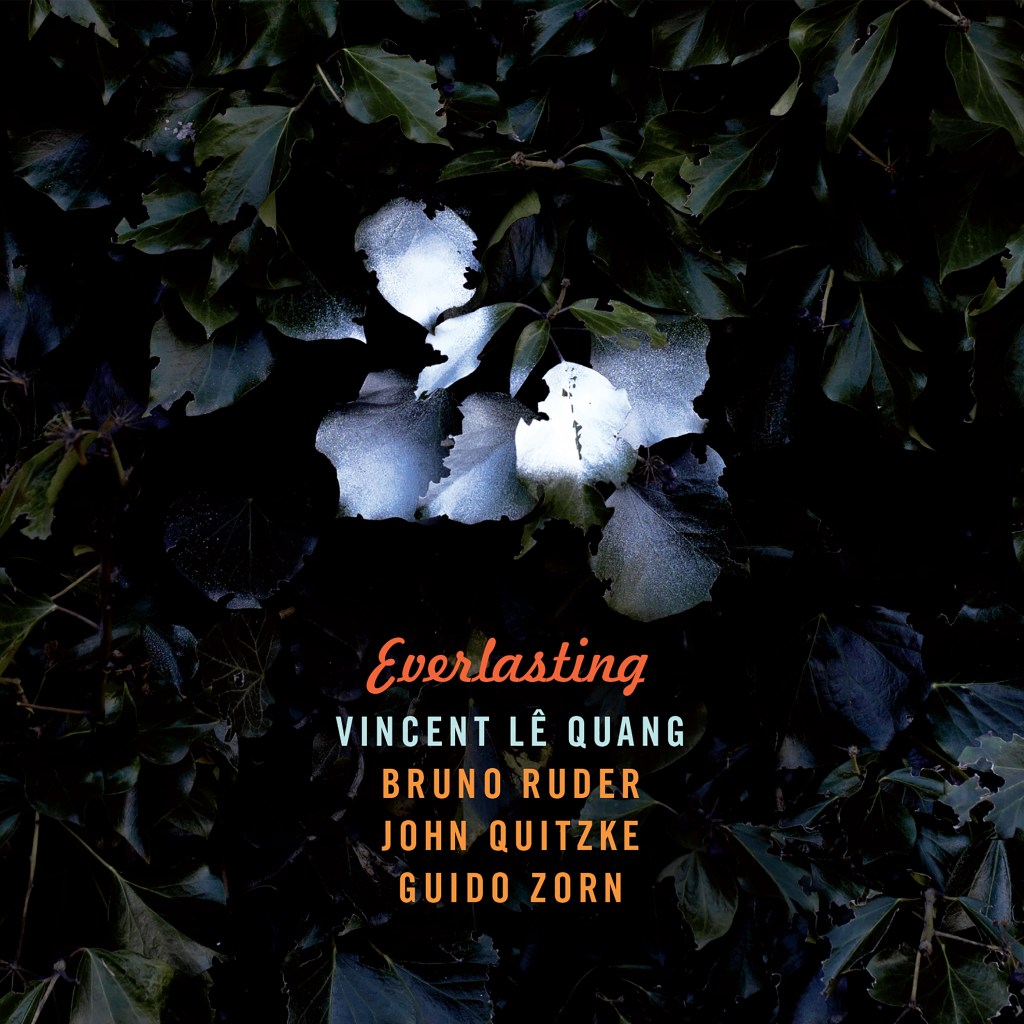

Vincent Lê Quang saxophones

Bruno Ruder piano

John Quitzke drums

Guido Zorn double bass

Recording, mixing, and mastering, Studios La Buissonne, Pernes-les-Fontaines, France

Recorded December 2019 and Mixed February 2020 by Gérard de Haro

Mastered by Nicolas Baillard at La Buissonne Mastering Studio

Steinway grand piano tuned and prepared by Sylvain Charles

Produced by Gérard de Haro and RJAL for La Buissonne label

Release date: May 21, 2021

Everlasting announces the leader debut of Vincent Lê Quang with a quiet assurance that feels anything but declarative. There is no display of ego here, no virtuosic flourish meant to dazzle. Instead, the album reveals a rarer mastery that effaces itself in service of listening. Lê Quang’s soprano and tenor do not dominate the space so much as inhabit it, breathing alongside pianist Bruno Ruder, drummer John Quitzke, and bassist Guido Zorn in a shared atmosphere where composition and improvisation dissolve into one another. What emerges is a music that seems already ancient, yet continually being born in the present.

This clarity of purpose stems from 12 years of collective life, the quartet bound by a mutual attentiveness that allows each piece to function as a portal to a clearer understanding of the self. Lê Quang speaks of his compositions as keys to a common state, and that metaphor becomes audible across the record. Each track opens a different interior landscape, yet all are connected by a shared commitment to the risk of being fully together in sound. Gérard de Haro’s production deepens this sense of communion, letting the music breathe within the luminous acoustics of Studios La Buissonne, where every resonance carries memory and every silence feels charged with possibility.

The album begins with an environment. In “L’odeur du buis,” piano and drums murmur from beneath the surface while the soprano rises gently into the night air, suspended above an arco bass that glows with lunar patience. Rather than announcing a theme, the piece slowly gathers a climate, a scent of darkness, foliage, and open sky. From this opening terrain, “La fugueuse” moves forward with subtle propulsion, water passing over unseen stones, the band drifting deeper into a current that neither rushes nor rests. These two tracks form a single act of arrival, a descent into the world the album will inhabit.

From there, the music shifts toward flowering and fracture. “Fleur” reveals some of the band’s most delicate interplay, cymbals shimmering with glasslike detail while Zorn’s bass traces a folk-tinged modal path. The group moves as one organism, loose at the edges yet inseparable at the core. This sense of collective breath reaches its most expansive form in “Everlasting,” a ballad built on tremor. Quitzke’s drumming hints at subterranean movement while piano, bass, and reed hold to a semblance of order, a belief that time can be counted. Gradually, that belief unravels. Flow becomes the governing principle of a rising density that never tips into excess, only into gravity.

A quieter inward turn follows. “Novembre” unfolds with the slowness of a season retracting into itself. This introspection deepens in “Une danse pour Wayne,” which refuses dance in favor of drift. Piano and drums speak in a near-telepathic dialogue, light touching darkness and returning transformed. Lê Quang’s soprano hovers above them, trembling with life yet strangely disembodied. Where these pieces search inward, “À rebours” stretches alone, a piano tendon extending between bone and air, longing without consolation.

The album then tilts toward the uncanny. “Dans la boîte à clous tous les clous sont tordus” begins with a solitary soprano that slowly gathers companions, the music assembling itself piece by piece. Tension accumulates, an electric expectancy that never resolves into release, and the listener is left suspended between dread and wonder. That unsettled feeling grows in “Le rêve d’une île,” a land that appears solid only to shift beneath the feet, and in “Rayon violet,” where breath rides atop shimmering harmonics, drawing a luminous arc through darkness.

With “Unaccounted-for pasts,” Lê Quang moves to tenor and opens a deeper register of uncertainty. The sound becomes cavernous, filled with echoes of memory that cannot be named. The album touches collective anxiety without ever becoming rhetorical, transforming fear into a shared vibration that binds the quartet more tightly together.

“Everlast” arrives not as a conclusion but as a threshold. The music hovers at the edge of sleep, brushing the listener with a tenderness that feels neither like a farewell nor a promise, simply a moment of contact. Consciousness thins, time loosens, and the sounds hover between presence and disappearance.

What this music ultimately gives is a space held in common, a quiet breathing room where listening becomes a form of companionship. Everlasting suggests a practice of attention that carries us beyond our habitual divisions of past and present, self and other, motion and stillness. In that quiet recognition lies its lasting power, an invitation to inhabit the space between knowing and listening, where meaning reveals itself on its own time.