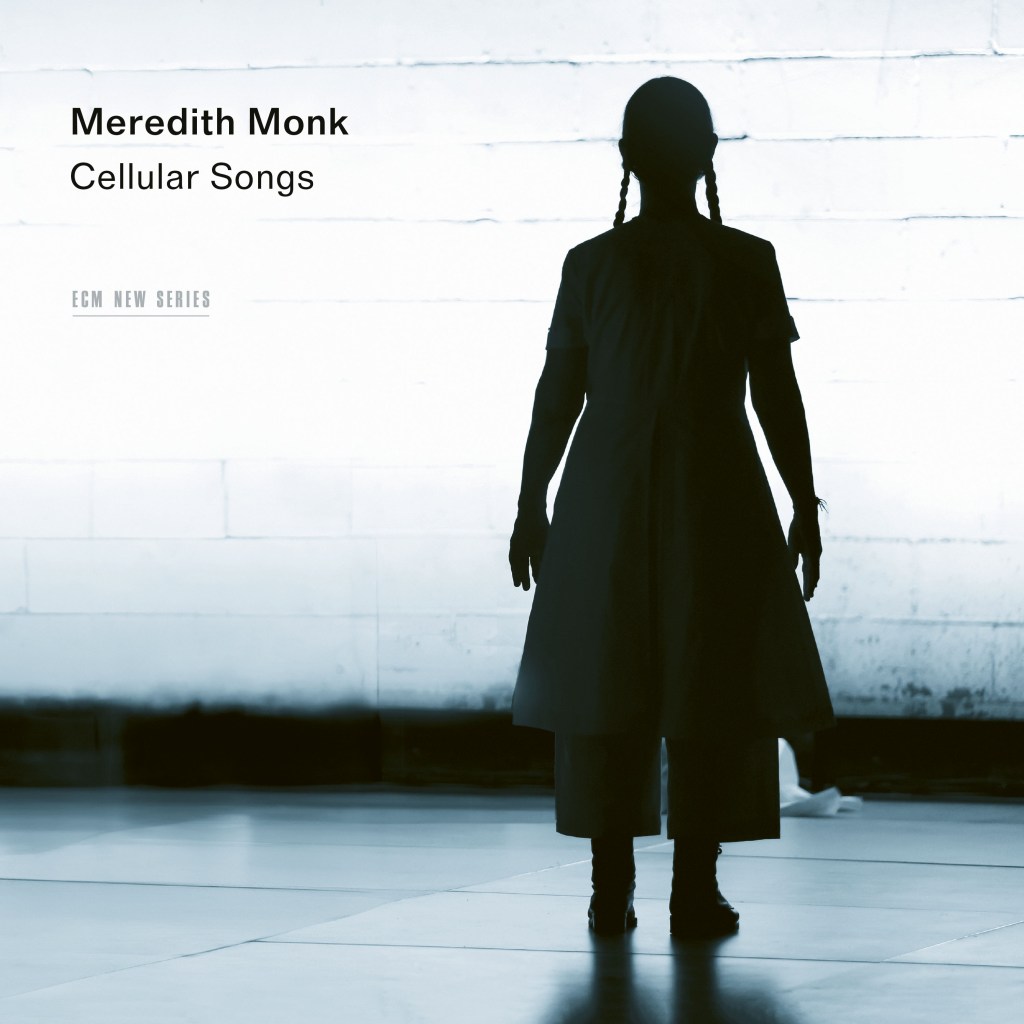

Meredith Monk

Cellular Songs

Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble

Ellen Fisher

Katie Geissinger

Joanna Lynn-Jacobs

Meredith Monk

Allison Sniffin

John Hollenbeck

Recorded January-March 2022 / March 2024

Power Station Studios, New York

Engineers: Kevin Killen (2022), Eli Walker (2024)

Assistant: Matthew Soares

Mixing: Eli Walker, Alexann Markus (assistant)

Cover photo: Julieta Cervantes

Recording producers: Meredith Monk and Allison Sniffin with John Hollenbeck

Executive producer: Manfred Eicher

Release date: October 17, 2025

All too often, women have been mythologically depicted as vindictive creatures who exist only to distract and destroy. Whether in the Sirens of the ancient Greeks or Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott, they sing, weave, and create in isolation, forbidden the pleasures of love, peace, and community. And while the work of singer and composer Meredith Monk has always been concerned with questions of agency, it was never made so clear to me as when the boxed set of her collected ECM recordings materialized in 2022. As the first album to appear since that watershed release, Cellular Songs doesn’t so much continue the journey as fold in upon itself, so that by the end, the listener is left with a compact flower of such potent expressivity that it seems capable of leading one’s ears in directions never thought possible yet which sound intimately familiar, as if remembered from a dream that preceded language.

Cellular Songs is the second part of a trilogy that began with On Behalf Of Nature, a work exploring our global ecosystem from a molecular vantage point. For Monk, the title names what is fundamental not only to life but to all of creation. “What is going on in the cell is so complex,” she writes, “and it’s a prototype of the possibility of what a society could be if you take those same principles and expand them.” As Bonnie Marranca suggests in her liner notes, composing and contemplation are synonymous, which makes Monk a meditator of worlds, one who reduces the act of communication to a microcosmic array of consonants, vowels, and blends. In this regard, it is difficult to imagine anything so biologically poetic as the opening “Click Song #3 Prologue,” in which Monk and her vocal ensemble (Ellen Fisher, Katie Geissinger, Joanna Lynn-Jacobs, Allison Sniffin, and Monk herself), with percussionist John Hollenbeck, get to the heart of things. Their tongue clicks are droplets in a distant cave, each carrying minerals and unfelt emotions until, over millennia, stalagmites rise as records of their passage. Like the three “Cell Trios” that follow, they constitute an internal code that locks into place. Flowing harmonies and dissonances encompass the breadth of life itself, a reality in which the voice is central, porous in its itinerant grace.

Hollenbeck’s vibraphone appears organically in a handful of pieces, a trace element in the soil of this music. Whether documenting a universal grammar in the syllabically potent “Dyads,” playing alongside the piano in “Dive,” or bowing a glassy surface in “Melt,” it allies itself with the building blocks of existence, defying the horrific structures so often fashioned from them. It is the vein in every vocal leaf, seeking photosynthesis without flesh and treating entropy as the dissolution of time. Sniffin’s pianism is equally cathartic in “Lullaby for Lise,” where she joins Geissinger. Rather than leaning on lyricism to seek fantasy, it straddles the threshold between waking and dreaming, recognizing that lived experience is always a blend of both. I hear it as a song to a child not yet born, gestating and growing with all the possibilities of time in her blood and brain, opening her eyes at last in “Generation Dance.” Thus, she comes to know the vision of her mother and her mother’s mother, and as she exhales in “Breathstream,” Monk’s solo voice gives shape to inherited traumas, now able to be wielded in the name of healing.

In the unfolding of “Branching,” each voice becomes the first in an ever-multiplying lineage of wisdom. Speaking of rituals and sacrifices, their repetition serves not as comfort but as a catalyst born of a primeval, generative power. “Passing” finds those same figures trading off vocalizations with a precision that is open to nature’s chaos, while “Nyems” reveals the playfulness of communication for the ephemeral metaphor it truly is.

Given that nearly all of the work presented here is stripped of linguistic meaning, what a radical blessing to encounter the coherence of “Happy Woman.” Here, the feeling is one of transparency, yet also of quiet critique, an awareness of the many roles women inhabit, whether by choice or by force. The opening refrain and its variations (“I’m a happy woman,” “I’m a hungry woman,” “I’m a thinking woman,” etc.) are the stitches of a mother among mothers, quilting herself into the patchwork of history.

By the album’s end, the sacredness of vibration becomes paramount. From these humming atoms emerge animals, rivers, and clouds, leaving us to wonder where the so-called intellect fits into the larger picture. Because if a heartbeat is nothing without silence, then its divisions are where forgiveness begins.