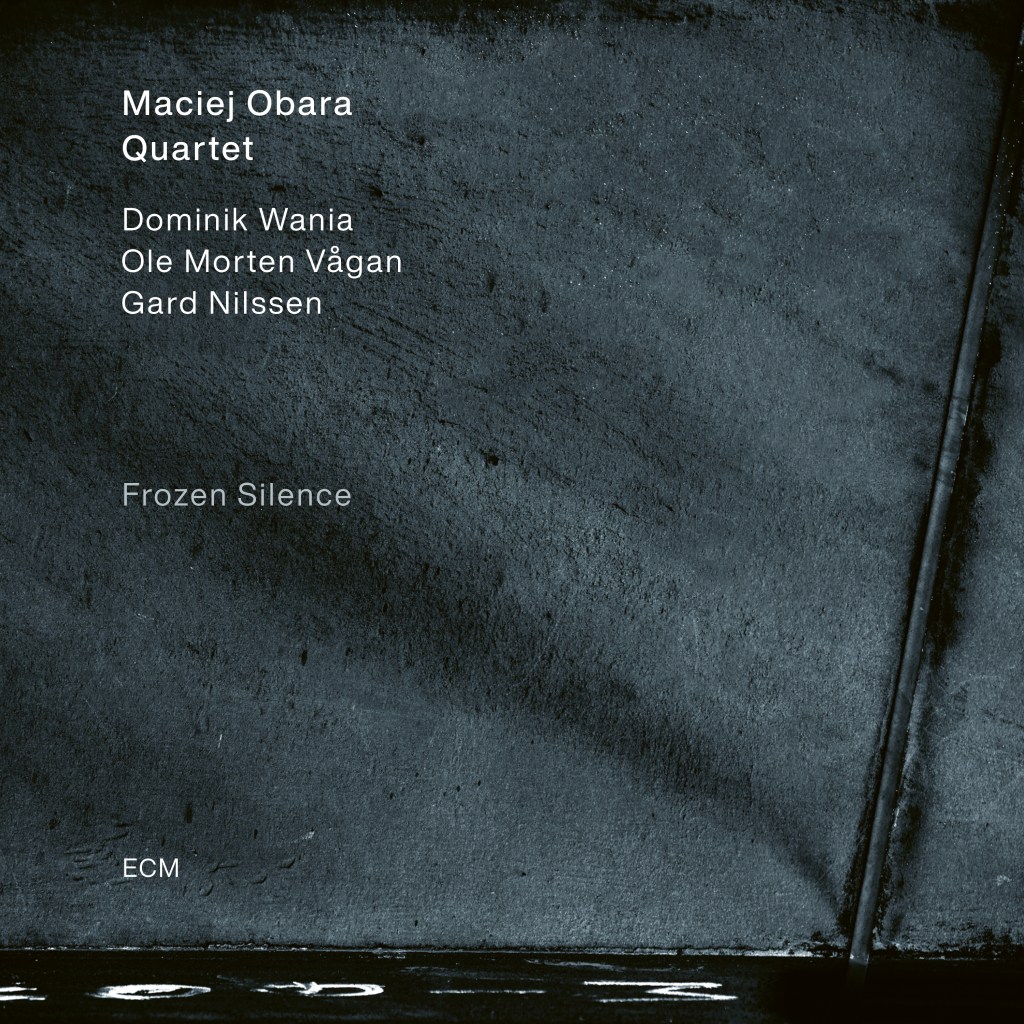

Maciej Obara Quartet

Frozen Silence

Maciej Obara alto saxophone

Dominik Wania piano

Ole Marten Vågan double bass

Gard Nilssen drums

Recorded June 2022 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Martin Abrahamsen

Mixing: Michael Hinreiner (engineer), Manfred Eicher, Maciej Obara, and Dominik Wania

Cover photo: Thomas Wunsch

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: September 8, 2023

For his third quartet outing for ECM, alto saxophonist Maciej Obara brings an ever-searching sound to bear on the foreground of a continuously shifting diorama. With him again are pianist Dominik Wania, bassist Ole Marten Vågan, and drummer Gard Nilssen. The tunes were inspired by Obara’s solitary travels in the natural scenery of southwest Poland, where he found himself wandering during the pandemic lockdowns. Such details work their way into many of the track names, starting with “Dry Mountain,” which lobs skyward before dipping down to touch the snowy surface of things. The ice is always moving, tectonic and ancient, even as the overall shape remains. (As in the later “High Stone,” the musicians are acutely aware of one another’s presence. With a grand sense of space, they reach far across tundra and time.) In the subsequent “Black Cauldron,” we encounter a brew of memories and impressions, a recipe as old as time yet with ingredients as fresh as the air we breathe.

The title cut has a delicate underlying groove, sewn into place by the precise needlework of Nilssen’s cymbals, while the glint of sunlight on a landscape brought to stillness by a world screeching to a halt speaks of brighter days ahead. The atmosphere is exciting in its possibilities, as if being alone were the only way to appreciate having others around. Vågan is gorgeously fluid here, lending so much humanity to the sound, the unerringly forward motion of nature continuing around him. Wania’s solo brings the touch of longed-for interaction, even as Obara’s flights keep their shadows in check.

Other notable turns of phrase include “Twilight,” a lullaby that unfolds with understated virtuosity and spotlights Obara’s talents as an improviser like few tracks before it, and “Waves of Glyma.” The latter recalls time spent on south Crete, populating the memory with joyful revelry, fearless camaraderie, and a feeling that life might never end. Amid the phenomenally upbeat rhythm section, Wania holds tight to the ethos of the hour.

One surprise inclusion in the set is “Rainbow Leaves,” a leftover from the bandleader’s Concerto for saxophone, piano and chamber orchestra, co-composed with Nikola Kołodziejczyk but now refashioned as an improvisatory seed. Obara is fiercely (yet never aggressively) beholden to wherever the melody wants to go, letting us tag along six feet behind.