This recording unfolds as a meditation on movement: of peoples, of sounds, of power, and of bodies both musical and political. Forged in the turbulence of the Enlightenment and shadowed by the first tremors of revolution, the repertoire gathered here belongs to a France that was simultaneously consolidating itself at home and projecting itself outward through trade, conquest, and imagination. The 18th century witnessed an unprecedented circulation of goods, ideas, and bodies, and with it came an uneasy reckoning. Curiosity and domination advanced together, and music became one of the most refined sites where that contradiction could be staged, aestheticized, and occasionally questioned.

As Marco Crosetto observes in the album’s liner notes, ports, salons, and theaters absorbed the sonic residue of these encounters. Foreign rhythms, borrowed gestures, and invented “elsewheres” entered French musical language not as faithful transcriptions but as carefully framed reflections of desire and anxiety. The exotic was never neutral. It arrived filtered through fantasy, hierarchy, and control, transforming distant cultures into mirrors for Europe’s own doubts about virtuous progress. Rousseau’s warning that civilization estranges humanity from itself hovers over this repertoire, not as philosophy alone but as sound. What Europe called expansion often sounded like displacement, and what it called novelty frequently concealed erasure.

At the center of this program stands another transformation, quieter but no less symbolic: the ascent of the cello. By the mid-18th century, its depth and resonance began to eclipse the viola da gamba, an instrument long entwined with aristocratic inheritance and established authority. This was not a clean overthrow. Old techniques were adapted, absorbed, and revoiced within new forms. The cello did not abolish the past; it reincarnated it. In that sense, the instrument becomes a metaphor of its time, negotiating between continuity and rupture, inheritance and reinvention.

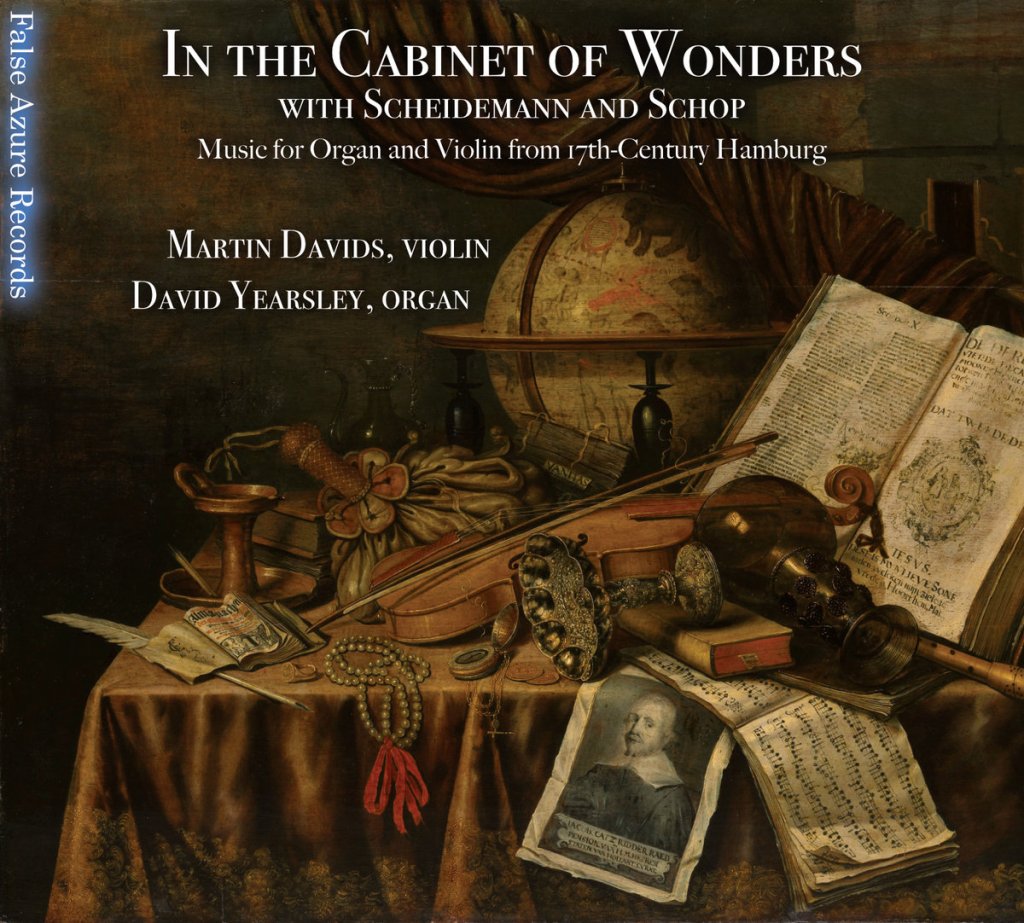

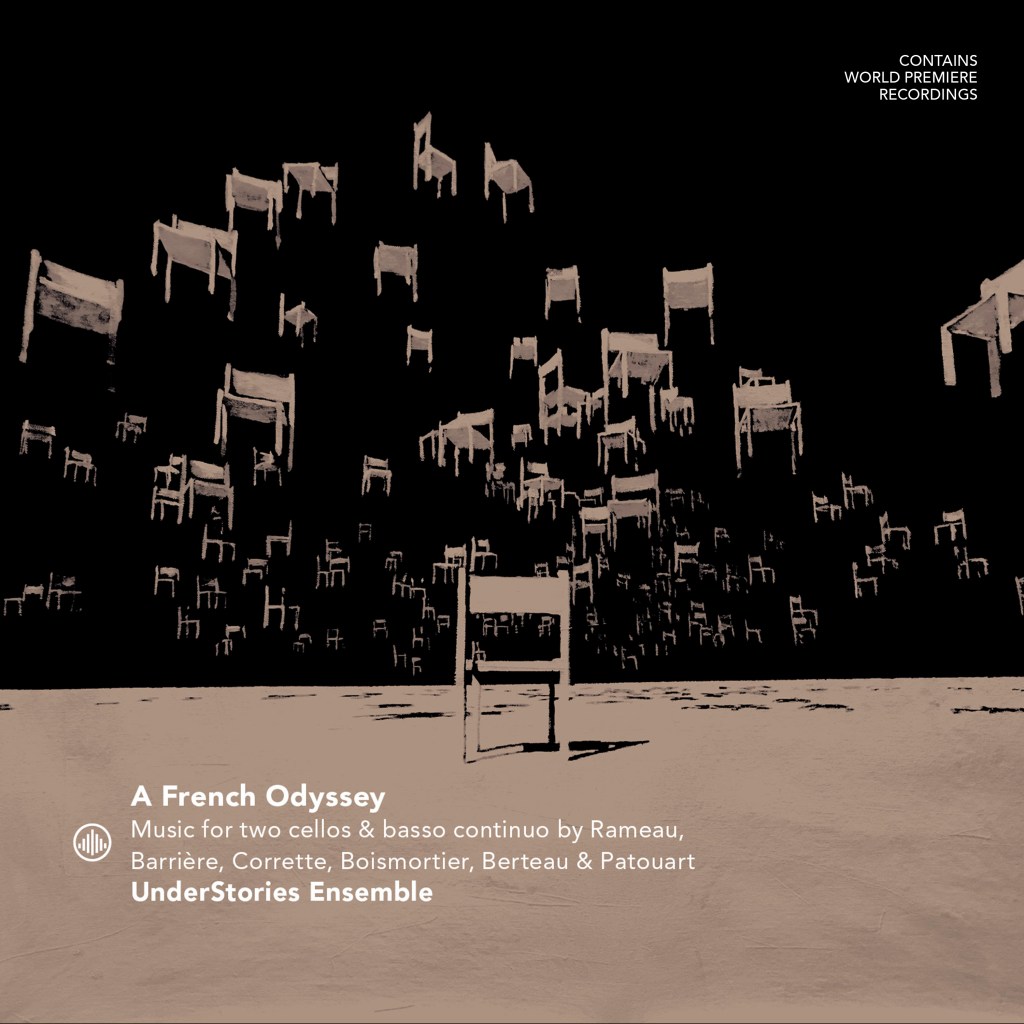

This philosophy animates the debut of UnderStories, a French-Italian Baroque ensemble that listens downward rather than upward. With Mario Filippini on viola da gamba, Loris Guastella on percussion, Marco Crosetto on harpsichord, Silvia De Rosso on violone, Margherita Burattini on harp, and Bartolomeo Dandolo Marchesi and Clara Pouvreau on violoncello, the group privileges the low register as a site of agency rather than accompaniment. Their approach embraces a Baroque freedom in which instrumentation remains fluid and arrangements remain provisional. The past here is not embalmed; it is negotiated.

Jean-Baptiste Barrière (1707–1747) offers one of the most eloquent articulations of this new cello identity in the Sonata a tre in D minor, No. 2, Book III (c. 1736). The opening Adagio unfolds with restrained longing, its melodic lines reaching outward as though aware of distance itself. The ensuing Allegro brightens the terrain without abandoning depth, allowing the ensemble’s tactile sonority to come fully into focus. Fingers, strings, and wood remain audible partners in the discourse, while the harpsichord gleams with controlled brilliance. The Aria sinks back into introspection, its melancholy exquisitely weighted, before the final Giga steps forward with buoyant resolve, dancing toward a horizon that remains deliberately unattainable.

Martin Berteau (1691–1771), trained on the viola da gamba and later a founding figure of the French cello school, embodies the transformation made audible. His Sonata a tre No. 6, Op. 1 (c. 1748) moves effortlessly between robustness and tenderness, never allowing one to eclipse the other. The harp’s presence lends an enchanted glow while also deepening the harmonic shadows beneath the surface. The central Siciliana stands as one of the album’s most persuasive moments, poised and inward, balancing restraint with warmth. Here, delicacy becomes discipline, and the ensemble articulates Berteau’s lines with refinement. This sonata emerges as a quiet manifesto for continuity through change.

Interwoven among these instrumental works are reflective pauses that clarify lineage. Marco Crosetto’s Prélude à l’imitation de Mr L. Couperin and Margherita Burattini’s Prélude à l’imitation de MM. Rameau et Naderman serve not as interruptions but as footnotes in sound. These solo interludes acknowledge ancestry while refusing nostalgia, reminding the listener that, in this century, imitation was a standard mode of dialogue.

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) looms over the program not merely as a composer but as a cultural architect. His opera-ballet Les Indes Galantes appears throughout in carefully chosen arrangements that foreground both its brilliance and its complications. The Ritournelle pour “Le Turc généreux” and the Tambourins I–II, arranged respectively by Bartolomeo Dandolo Marchesi and the UnderStories Ensemble, pulse with rhythmic vitality and folk-tinged energy. Percussion and interwoven strings generate an intoxicating surface, yet beneath the dance lies a careful staging of difference. Rameau’s music constructs the foreign as spectacle, inviting admiration while maintaining control.

This tension becomes more explicit in the Air pour “Les Sauvages” and Air pour “Les Esclaves Africains”, both arranged by Clara Pouvreau, as well as the Air des Incas, arranged by Silvia De Rosso. These pieces dramatize otherness through bold rhythm, percussive force, and ceremonial pacing. They reveal how European music transformed colonized peoples into sonic symbols, vessels for projected fantasies of innocence, savagery, or nobility. The ensemble’s gravelly strings and emphatic rhythms refuse to smooth over this history. Instead, they allow the weight of representation to be felt, asking the listener not merely to enjoy the sound, but to interrogate its framing.

That interrogation deepens in Rameau’s “L’Égyptienne” from Nouvelles Suites de pièces de Clavecin RCT 5–6, arranged by Bartolomeo Dandolo Marchesi. The piece is a dramatic masterstroke, yet its allure destabilizes admiration itself. Exotic color here becomes a lens of appropriation, reminding us that fascination often coexists with domination. The music dazzles, then unsettles, forcing a reckoning with the cost of its own beauty.

Louis-François-Joseph Patouart (1719–1793) brings the program into remarkable focus with the Sonate en trio pour deux violoncelles et une contrebasse No. 6, Op. 2 (c. 1750), presented here in a world premiere recording. The opening Adagio unfolds with luxuriant depth, the instrumental blend feeling both inevitable and freshly imagined. Gavottes follow with confident verve, their brightness never shallow, while the Minuettos grow from gentle poise into declarative presence. The music seems to test its own balance between symmetry and surprise.

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier (1689–1755) contributes a different energy in the Sonate en trio No. 5, Op. 37 (1732). Its opening movement bursts forward with rhythmic assurance, pressing against borders rather than merely crossing them. The central Largo finds unexpected poignancy, pausing to reflect before the final movement reasserts momentum with dynamic wit. Boismortier’s voice here feels pragmatic yet searching, a composer aware of the pleasures of motion and its costs.

Michel Corrette (1707–1795) closes the journey with “Le Phénix,” concerto pour quatre violoncelles, violes ou bassons(c. 1735). The work’s lively opening ushers the listener into a richly variegated sound world, followed by a tender slow movement that invites collective listening rather than display. The final Allegro rises with confident vitality, its interplay among strings suggesting renewal without amnesia.

By the end of this album, motion itself emerges as the central theme. Instruments migrate, genres adapt, and cultures encounter one another in asymmetrical exchanges that leave lasting marks. UnderStories does not attempt to resolve the contradictions embedded in this repertoire. Instead, the ensemble listens into them, allowing beauty and unease to coexist. In doing so, the recording offers a philosophical proposition as much as a musical one: that history speaks most honestly when we allow its fractures to resonate, and that listening, when practiced with care, can become an ethical act. The past does not ask for absolution. It asks for attention.