Kim Kashkashian viola

Münchener Kammerorchester

Alexander Liebreich conductor

Boston Modern Orchestra Project

Gil Rose conductor

Kuss Quartett

Recorded between 2006 and 2008 in the USA, Poland, and Germany

Engineers: Peter Laenger, Lech Dudzik, Gabriela Blicharz, Joel Gordon, John Newton, Blanton Alspaugh

Produced by Manfred Eicher

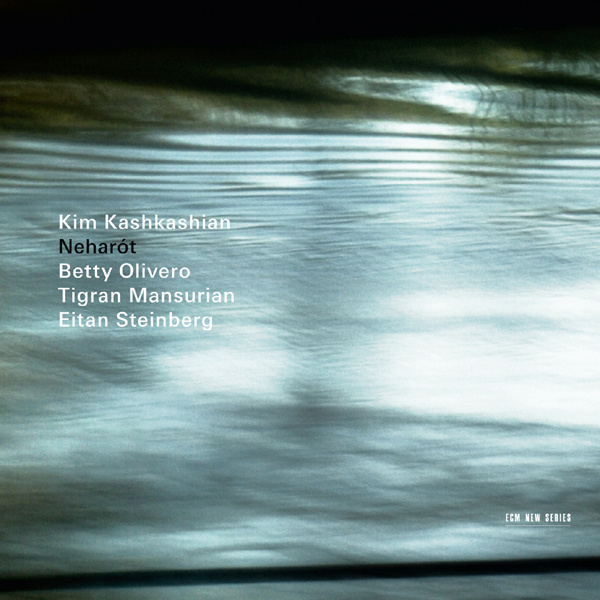

Neharót Neharót (2006/7) for viola solo, accordion, percussion, two string ensembles and tape by Israeli composer Betty Olivero opens a haunting album from violist Kim Kashkashian. It is a slow awakening—not into light, but into twilight—and swells with the wounds of fresh tragedy. Kashkashian arrives as if by wind and with the raw imperfection of an unpreened bird. The tone and feeling are not unlike that of John Tavener’s The Protecting Veil at its tensest moments. The strings roil like turgid waters in which eddy the relics of an unseen war. Two women’s voices reach into the storm with tendrils of mimicry. This call and response blossoms into a profound moment of rupture, at which point the orchestra and percussion spill over one another. Fragments of the audible past come through as snatches of Monteverdi quoted from his Orpheus and eighth book of madrigals. These recycled motifs are like a dream that quickly consumes itself before waking again. The viola rises in their place, seeming to run around frantically in search of the voices that so enlivened it. When they are nowhere to be found, the outcast wallows in the hopes that nightfall will be her cloak. But then the voices come back: the viola prostrates itself, fearing to expend the ancestral legacy it breathes. It wants nothing more than to offer gratitude, but can only contort itself into a vowel of need.

After such a profoundly draining journey, the three Armenian selections that follow are a welcome rest, though one not without its internal travels. Tigran Mansurian gives us his Tagh for the Funeral of the Lord for viola and percussion, Three Arias (Sung out the window facing Mount Ararat) (2008), and Oror, a lullaby by Komitas (1869-1935) arranged and performed here by Mansurian at the piano. The “tagh” is an ancient Armenian song, and Mansurian’s breathes with organic vitality. Its lament echoes across cold plains, the percussion a mere accent to the viola-driven melody. The Three Arias are essentially a series of orchestral swells with viola interludes, an audio essay of the music’s own origins and possible futures. The viola acts like a lens over a film sheet, trying to find the one picture that most clearly articulates something that can only be remembered through image, but that can only be musically described. The viola struggles with an unseen force in spite of its orchestral inheritance. A dazzling ending is made all the more so for the effort required of us to get there. And this is precisely what the piece is about: seeking out those moments that, in a life remembered, also define that life most clearly. Mansurian’s interludes are like the passage between two days, a conduit between continents and cultures, a subtle diaspora of sound.

And so, by the time we return to Israel in Eitan Steinberg’s Rava Deravin (2003) for viola and string quartet (the tile means “Favor of Favors”), we feel more fully prepared for any and all emotional obstacles. The piece was originally scored for voice and a mixed chamber ensemble, but was transcribed as the current version at Kashkashian’s behest; hence the accordion-like opening harmonics that speak of bellowed breath. Yet even before the music begins, the instrumentation tells us so much about what we are about to hear. We know the viola soloist has a second self, a ghost presence amid its accompanying quartet, and yet here it is at once extracted and embedded in its periphery, singing with its own voice even while knowing it has been long aligned with the larger organism behind it. When the quartet takes a more syncopated stance, we never lose sight of the abstract milieu in which it is situated. The viola must resign itself to self-division, and toward the end it squeals and scatters snake-like through tall grasses of harmonics. The music dies not by lowering itself in volume, but by pushing us away so gradually that by the time we notice the music has gone, we are already too far away to catch up with it.

Were the orchestra to be analogized as body, the viola would most certainly be the throat, for the vibrations of song rattle its chambers more than those of any other. In this respect, Kashkashian has given more lucid breath to this recording than to any other she has made. She only seems to get better with every draw of her bow, and her dedication once again remains paramount. This is a cohesive program of some of the most original music to come out of ECM in a long time. Not to be missed.