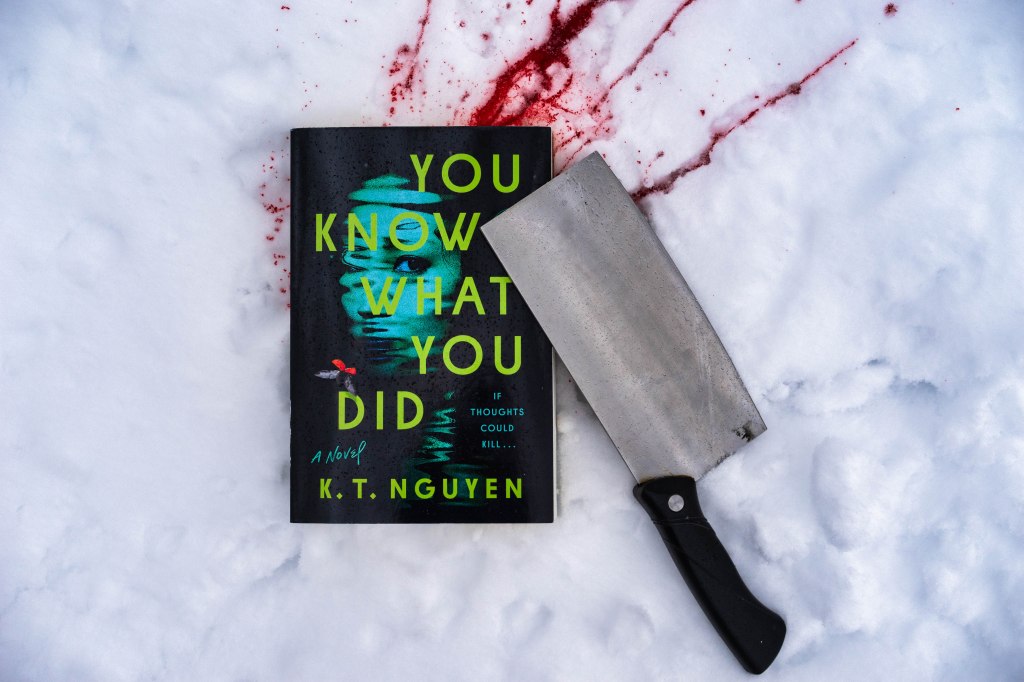

Little-t “trauma” operates by a different MO from big-T “Trauma.” Throughout You Know What You Did, the debut thriller from K. T. Nguyen, we are pulled between the two in a narrative balancing act of such agility as to leave us en pointe at their intersection on every page.

Artist, mother, and wife Annie Shaw is more than this trifecta lets on. Living in suburban Virginia with her husband Duncan and their daughter Tabitha, she has buttered the bread of her life on both sides. And yet, molding between them is a sandwich of reruns involving incidents she would much rather forget. Dead bodies, bloodied hands, and other morbid highlights make us wonder just how much Annie may be capable of when her thoughts are allowed to roam. But roam is all they can do under the medication she takes to corral her OCD, which operates by its own rules of contamination that must be taken seriously whenever they jump the fence.

Haunted by thoughts of her mother, whose death is a leak in her otherwise airtight self-presentation, Annie sinks her canines into the absence as if something to devour in one bite. She worries what the authorities might think were they to scrutinize her magazine-worthy home (at one point described as a “Pinterest board come to life”), let alone the immaterial desires living under its roof. Above all, she fears herself.

We learn that Annie’s parents came from war-torn Vietnam to start afresh in the States. Yet the story of this turnaround is a myth to which she has grown apathetic. She lets the minds of those she encounters fill in its gaps with American grit and self-determination as an excuse to ignore their complicity in a genocide padded by hindsight. Wrapped in layers of denial, her heritage avoids the tip of the proverbial tongue like a cherry tomato dodges the prongs of the salad eater’s fork.

Lest we tokenize her emotional inheritance like the rest, Nguyen reminds us of just how broken everyone in Annie’s circle is. Duncan carries his own PTSD from as a Pulitzer-winning military field reporter. His refusal to talk about his work speaks of a silence inaccessible to Annie, who is constantly being forced to reveal her innermost thoughts, ever the one to “smooth things over.” The novel’s happiest people are those who have trained themselves in the art of looking the other way.

And so, when her long-time art patron goes missing, Annie starts to unravel, slipping down drains of thought that may or may not be her own. Throughout this storm of possibilities, refrains rear themselves. Whether in the rising temperatures of her showers (which seem to be her only solace) or in the admonitions of a mind in turmoil, she gives in to speculation at the risk of harm. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that said patron always says Annie’s name twice (“Anh Le, Anh Le”) or that her long-haired dachshund should be named Deja, implying that even the most indeterminate circumstances might be born of rehearsal.

In childhood flashbacks, we witness an upbringing tessellated with white squares of affirmation and black squares of a mother whose decline begets abuse. When everything in Annie begins to hurt, we realize she has always been in pain, but the extent of it is only clarifying itself now. After decades of Mother opening wounds and Daughter suturing them, the latter is left wondering who will supply the thread when it runs out.

Meanwhile, the rough patches are spreading. Annie takes compliments wherever she can get them. Upon meeting a handsome stranger, she relishes seeing herself in his eyes, as perfect as anyone can be in that blush of unfamiliarity before the truth sets in. But flowing through those endorphins is a curse, a toggle by which the internal bad and external good may switch places at any moment. Annie may be a “master of creating worlds,” but she can barely hold the seams of her own.

With adroit control over tension, Nguyen keeps us in check, even when we only have one foot in the circle of certainty. As the kinetic ending snaps everything into focus, we begin to question our allegiances to mental (in)stability, collective trauma, and self-made idealism.

While no one is innocent, that’s perhaps as it should be. We are all vagabonds from something: our pasts, our ancestors, our very selves. If anything, the moral gray areas in which these characters live confirm the messiness of the mundane. Thus, the biggest crimes are those committed in the everyday. Whether it’s Annie’s admission to hiding behind her husband’s privilege or a friend’s nonchalant acquiescence to infidelity, in each of these indiscretions floats a keyhole waiting to unleash the floodgates of sin—a painful yet necessary reminder that no war ever ends because the soul is a battlefield on which blood never dries.

You Know What You Did is available from Dutton in April 2024.