PRAXIS SELECTION feels less like a compilation than an ongoing physiological test, an attempt to discover what images can endure before collapsing into pure sensation. Drawn from the sprawling PRAXIS cycle (2007-2015), these forty pieces, of which the below only touches upon highlights, operate as a catalogue of intensities that never buy into logic. As Stefan Grissemann astutely observes, Dietmar Brehm’s “secular icons irritate precisely because they never reveal their aim, often not even disclosing what is happening in and to them.” They do not point toward meaning so much as enact its very possibility, stripping “praxis” of any political or ideological inheritance in favor of naked dissociation.

Brehm moves from erotic to clinical, from diaristic to abstract, yet each mode is a membrane that can be pierced, stretched, or contaminated. The digital clarity of the later entries is abraded by bumped microphones and the sounds of equipment being dragged, as if the assembler were refusing the illusion of being “hands off.” Even the concluding glyphs that begin to appear are cryptic enough to obscure what precedes them. As our vision is heightened, impaired, and rerouted, we are left caught in the performative residue of it all.

A few distortions of reality serve as anchors for the larger constellation. 1000 Blitze (1000 Bolts) turns lightning into a vascular network, an illuminated anatomy of perception that overwhelms the sensorium. Vision feels compromised yet somehow more acute, as if the eye were seeing its own interior. Himmel (Sky) distills the world into a single fly drifting in an impossible blue expanse while rain murmurs in the soundtrack. The insect is reduced to an atmospheric event, a coherence of sentience within a monolithic field. Here, Brehm demonstrates how minimal stimuli can trigger an almost cosmic alertness.

This shift from the microscopic to the elemental reappears in Übung (Exercise), where a figure is thrust toward the camera, lit as if by an emergency sign from within. Strobes slide across sweat and skin until the figure becomes particulate, edging toward ash. Schwarzensee repeats the experience through landscape: bands of colored water glide past while the creak of a rowboat grounds the abstraction in human effort.

The domestic sphere proves no safer. Vollmund (Full Moon) frames eggs frying, cigarettes burning, Coke bottles bending, and a child’s cheerful “Let’s go,” all glimpsed through a circular aperture that turns the mundane into a pupil of surveillance. In Basis pH, the application of makeup is a study in exposure rather than beautification, as if each gesture were removing a layer of self-protection rather than adding one. It’s the private act as uncertain confession.

Brehm’s engagement with pornography punctuates at regular intervals but refuses eroticism. Peng Peng links desire to violation by intercutting voyeuristic gazes with surgical imagery, whereas Berlin and Paris tint fleshly negatives green or red-blue until their physics appear industrial.

Self-portraiture assumes the identity of a malfunction. Chesterfield shows Brehm flickering beside a car while a metronome hammers machinically. In Charles, a drained, remorse-free face is doubled by a twin that never quite aligns, enacting a moral vacancy. Röntgen (X-Ray) meshes screaming vocals with inverted faces and vehicles in a radiographic exorcism. Such pieces insist that identity is not a stable referent but an affectation that appears only when stressed, inverted, or pulled apart.

As chronology grows, so does the gentility of Brehm’s touch. Licht (Light) is a standout in this regard: a hand caresses a lampshade again and again in a manner so tender that it borders on obsession. Sonne Halt (Sun Stop) freezes the sun between two towers as a red circle that pins luminosity to the board of life without extinguishing it. Cocktail shifts into a reflective register as Brehm diverts focus to his layered image, jazz sketching itself in the background.

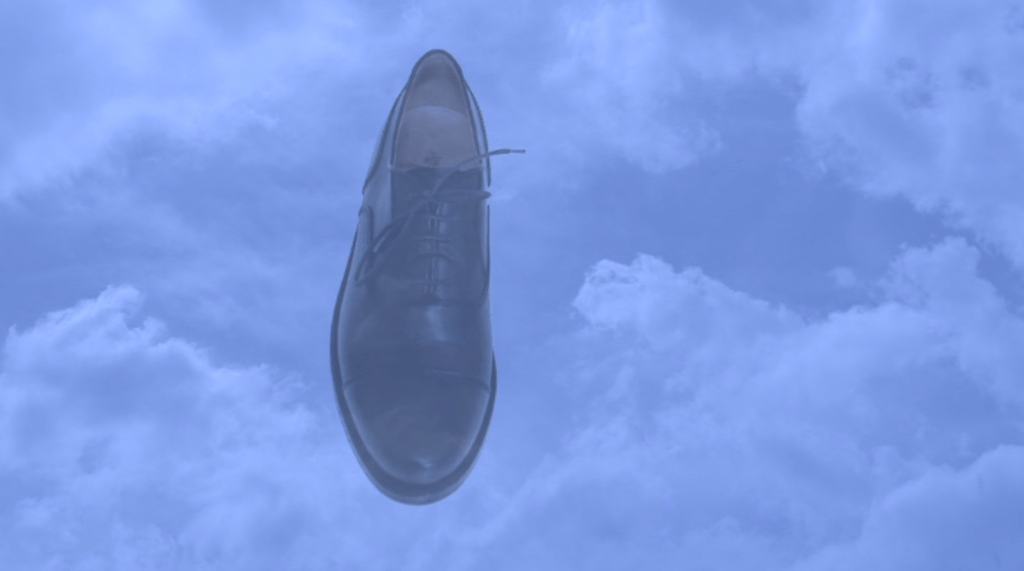

The selection concludes with uncanny simplicity. Oxford holds a pair of dress shoes against the firmament. Walking on air? Hello Mabuse converts a simple handshake into a bureaucratic nightmare, framed by ominous clocks. And Rolle returns to repetition as ritual, walking toward and away from the camera near a bale of hay until the act becomes a mantra.

Throughout PRAXIS, Brehm interrogates the image’s ability to signify anything beyond material agitation. The cumulative effect is fiercely corporeal, working directly into the viewer’s nervous system. Along the way, we learn how recognition and estrangement can collapse into each other, how ordinary objects can become alien through intensity, and how a soul caught in the act of looking cannot help but feel implicated in what it sees. What remains is a kind of hyper-alive exhaustion. Brehm exposes the vitality of the photographic trace even as he acknowledges the slow death embedded in every act of viewing. These fragments do not cohere, yet their incoherence is the point. Are we really so different?