“The pond is the teacher, underwater lies the source.”

–David Rothenberg

Near the apartment complex I once called home, before I migrated to my present dwelling, a pond would awaken each night in amphibious utterances. Frogs, crickets, and invisible choir members released a polyphony of chirrups and croaks that spilled into the humid dark. It was alluring enough that I found myself inventing post-meridian errands just to step outside and listen. I remember how the air trembled with that sound, neither wild nor domestic, a liminal language that both invited and eluded comprehension. I never tried to categorize it then; it was enough to be absorbed. What struck me most was its irregularity, a music without time signatures, and yet, the longer I listened, the more I could discern the soloists from within, the deliberate from the accidental. What I did not realize, however, was that this was only the surface of a deeper, secret orchestra playing just beneath my feet.

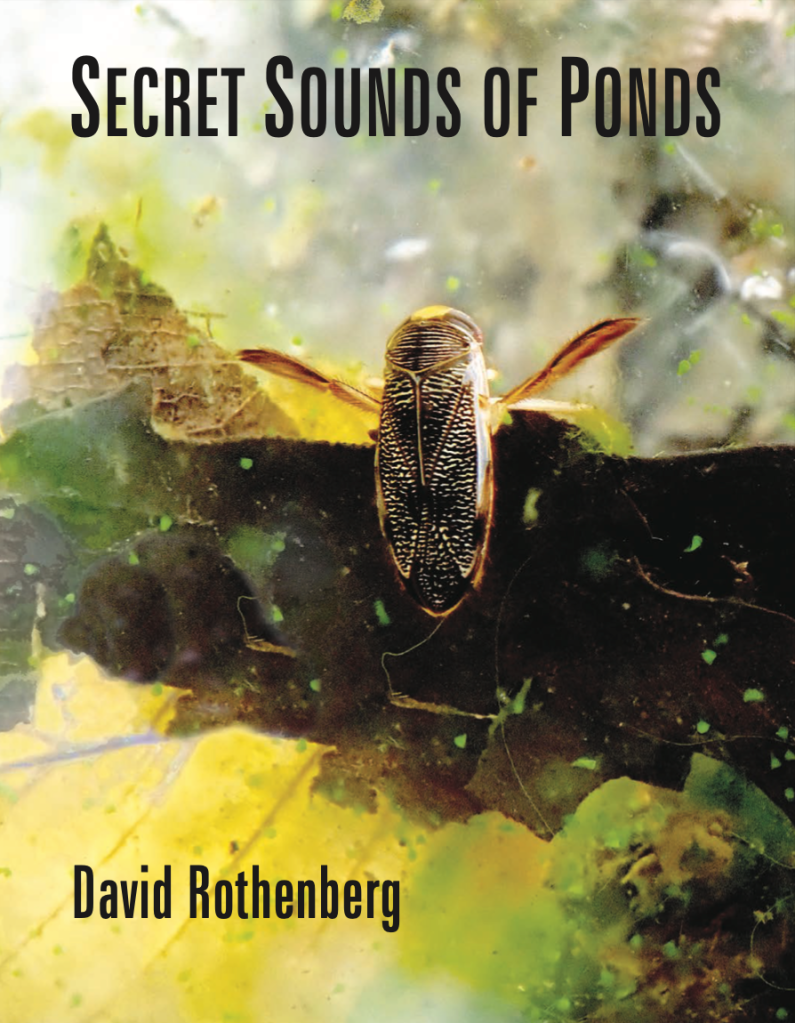

It was during the stillness of the pandemic that musician, philosopher, educator, and animal collaborator David Rothenberg turned his own attention downward. He found that ponds, those apparently placid mirrors of sky and branch, are paradoxical entities: tranquil to the eye, yet pulsing with invisible sound. Above the water, a hush. Below, a thicket of sonic life. But how does one hear through liquid? Rothenberg, already attuned to the songs of whales, found his usual instruments inadequate. He commissioned a hydrophone capable not merely of recording but of touching sound, translating the tactile shimmer of aquatic vibration into something audible. In doing so, he discovered not merely a pond but a pulse, a murmuring node within the living organism of the planet. In this submerged language, he recognized that the world itself is always breathing, whispering, and improvising at the edge of consciousness. The recordings discussed and contextualized in Secret Sounds of Ponds feel like a revelation, a form of listening that brushes the hair of the mind, a continuous and organic ASMR channel that one can tune into and out of at will.

Yet the music is not only animal. The flora, too, contribute their delicate speech: plants releasing oxygen bubbles as miniature offerings, each a syllable in an ancient conversation. “The plants keep time,” Rothenberg notes, “and the beasts carry a tune.” One hears this and realizes how naïve our auditory hierarchies have been. We’ve long believed that sound belongs to the realm of motion, of bodies and breath. Yet here are rooted beings, singing through photosynthesis, metronomes of life itself.

Rothenberg reminds us that “even in this century where everything seems possible, morphable, changeable, hearable, findable at a moment’s thought, there are still sounds around us… immediate sounds that we still don’t know.” If we are ignorant of our surroundings, perhaps we are equally ignorant of our origins. We imagine that knowing where we are going requires understanding where we’ve come from, yet Rothenberg suggests the opposite: that both the departure and destination are wrapped in the same sonic fog. Thus, we meet the limits of our perception and the possibility that such limits are spiritual. The indistinguishable becomes indistinguishably beautiful. Insect, fish, turtle, plant: all’s fair in love and pond life.

This mode of listening is not a science but a humility. It compels us to ask impossible questions. If technology must translate these frequencies for us, were we ever meant to hear them? When we call this music, do we consecrate or colonize it? Is it communion or interference? Somewhere, I imagine, John Cage laughs from the beyond, his silence perforated by the croak of a frog.

“For all the millions of hours we have spent together with animals,” Rothenberg observes, “we still cannot speak with them.” The task, then, is not to translate but to collaborate, to become co-musicians in a score that predates our language. Sound may have no intention, no recipient, and yet we crave both. We are instruments yearning for meaning, resonating for a moment before fading into the dissonance of time. Listening, as Rothenberg reminds us, “reveals things alive before we can claim them.” This is the ethical heart of the project: listening not to possess but to participate. Without that transformation, we remain voyeurs; with it, we become apprentices in the grammar of existence, learning not to compose but to decompose, to take apart what our words have wrongly fused.

I think here of Bashō’s immortal haiku, in D.T. Suzuki’s translation:

Into the ancient pond

A frog jumps

Water’s sound!

It is easy to romanticize this image, to see it as a vignette of simplicity. Yet the poem’s true profundity lies in its inversion: the pond, not the frog, is the voice; the frog merely the activator, the finger on the cosmic key. That the frog is jumping into a pond is never in doubt, yet translators have long struggled to articulate that final sound—“splash,” “plop,” “water-note,” “kerplunk”—but perhaps that indeterminacy is the point. The sound eludes capture because it was never meant to be caught. Like Rothenberg’s recordings, made accessible via QR codes throughout the book or online in album form as Secret Songs of Ponds, it dwells in the space between articulation and silence, between perception and being.

Hence the human impulse to name: to label every ripple and rustle—scratching, blipping, bubbling, warbling—as if taxonomy were intimacy. Rothenberg resists that impulse by layering his own clarinet into the watery mix, joining a chorus rather than leading it. His collaborations with Ilgın Deniz Akseloğlu, whose deconstructive poetry conjures an invented language of resonance rather than reference, push this further. Her contributions hover like dreams, vocal fragments rising from the mire of the unconscious. Listening to “I Still Don’t Get How Distance Works,” one feels time dissolving; her voice becomes an echo of the pond itself, diffused and omnipresent.

In other tracks, Rothenberg’s clarinet drifts like an inquisitive creature among the bubbles and squeaks—curious, reverent, never dominant. I am reminded of Ornette Coleman’s philosophy of sound as motion through possibility: music as exploration, not arrival. Elsewhere, the pond alone is permitted to speak, recalling early electronic composers like Ilhan Mimaroglu, who inverted futurism into introspection, aiming their microphones inward to locate the primordial hum within us all.

Most of all, I think of Akifumi Nakajima, a.k.a. Aube, whose sonic investigations of fire, air, blood, and brain waves sought the inner pulse of matter itself. To engage with Secret Sounds of Ponds is to place a stethoscope against the earth’s waterlogged chest and hear it crackle. Rothenberg confesses, “I don’t play with the pond, but the pond plays with me.” That inversion, again, is key. The artist becomes the instrument, the listener the medium. This is not music about nature; it is nature using us to make itself known.

There is a sacred vertigo in such encounters. What begins as fascination turns toward reverence, even dread, as one senses the immensity of what vibrates beneath the apparent stillness of the world. Ponds, like temples, are mirrors of our incomprehension. They draw us inward until we see that to listen is to surrender.

And so, whenever I pass a pond now, I find myself wondering not merely what lives there, but where it came from. Science offers its explanations of erosion, accumulation, and equilibrium, but the heart refuses to hear them. The mind insists on something older, more mysterious: that the earth itself opened a small mouth to breathe, and we, by accident or grace, happened to hear it.