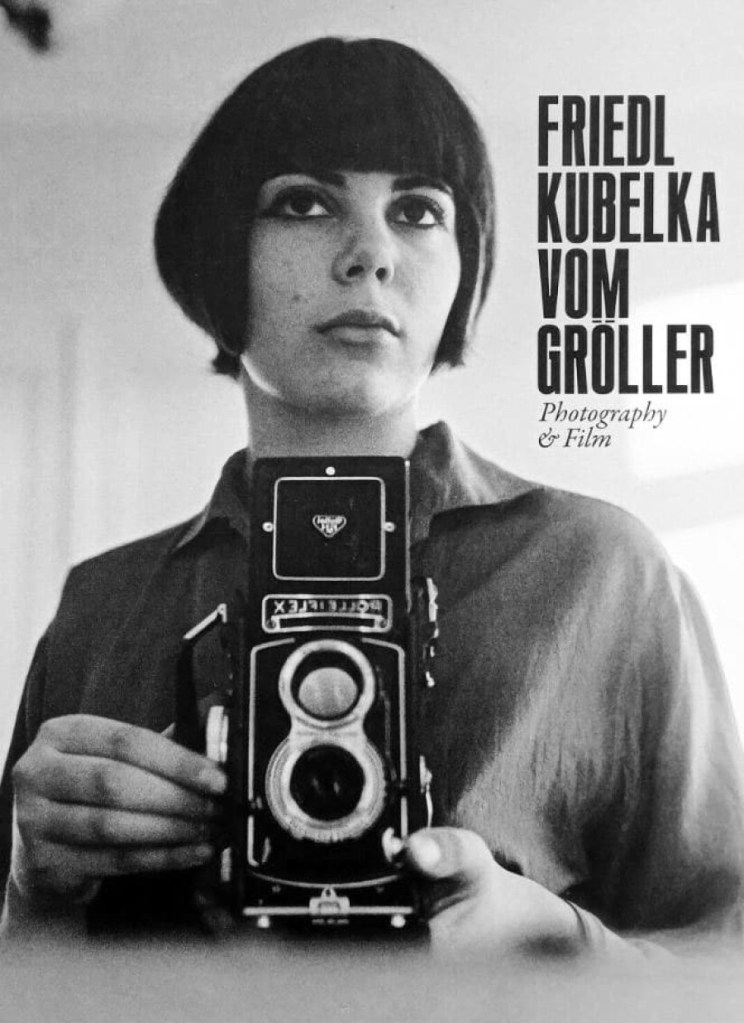

To approach Friedl Kubelka vom Gröller’s work is to enter a visual conversation in which portraiture reverses its usual direction. Instead of externalizing the internal in her subjects, she internalizes the external. The images behave less as windows than as mirrors, each a sobering reflection of our desire to read emotion, history, and truth into faces that refuse to perform. As Andréa Picard notes, Gröller is a practitioner of “intimate encounters” in which individuals are neither exposed nor captured but held in suspension at the threshold of recognition.

This suspension permeates the early pages of INDEX’s first book edition. The photographs therein, printed with honest lucidity by Christoph Keller Editions, show faces emerging mid-breath. Simultaneously present and withdrawn, they tremble between suffering and serenity. Her grid structures, most famously the Lebensportrait Louise Anna Kubelka series that documents her daughter weekly from birth through adolescence, unfold like a filmstrip. The blank squares where images are missing take on equal significance: temporal fractures, absences in maternal memory, interruptions in the fragile ritual of steady observation. These sequences echo the formal logic of cinema, built from illusions of continuity shaped by the cutting room.

The Jahresportraits, taken every five years from 1972 onward, chart not only the forward march of aging but also the atmosphere of an entire life-world. Melanie Ohnemus situates them within a feminist reclaiming of bodily autonomy. Within this context, the 1970s self-portraits, especially the Pin-Ups series, create a counter-archive. Saturated in color, refracted through ceiling mirrors or segmented by architectural lines, they mimic the vocabulary of glamour photography while disrupting it from within. Seductive yet confrontational, carefully staged yet emotionally exposed, they insist on a form of visibility that resists conventional consumption.

Even her fashion photography, an early professional pursuit, elicits shades of disobedience. Although commercially viable, the images perform what Ohnemus calls a “false copy” of the genre, “acting almost defiantly in the face of normative style conventions and countering obstinate references with consistent assertion of individual aesthetic autonomy.” They exhibit awkwardness, vulnerability, and small slippages where faces or bodies stutter against the camera’s demands. In her interview with Dietmar Schwärzler, Gröller explains this approach with disarming clarity: “For me, the psychological aspect was always important and also the creation of intimacy, even when I don’t know the person in front of the camera.” Said intimacy is never sentimental. It develops through exposure.

Her films, collected on the accompanying DVD, You. Me too., behave as “moving photographs,” as if time itself has begun to oxygenate the still image. Silence dominates, carrying a weight that spoken language cannot.

Erwin, Toni, Ilse (1968/69), her first film, contains the seeds of her entire creative approach. Among the three subjects, her friend Ilse is the most poignant arbiter of truth. Having been filmed after a suicide attempt, she oscillates between resilience and brokenness. The film neither diagnoses nor consoles; it waits, aware that the environment belongs to a person’s portrait as much as their features do.

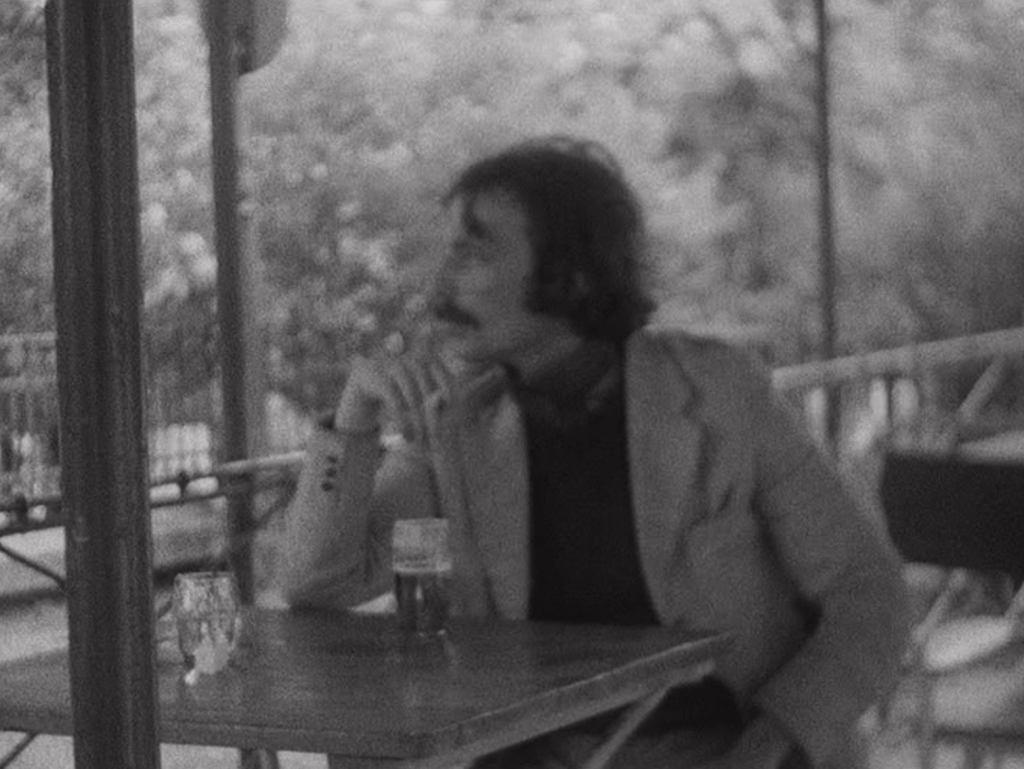

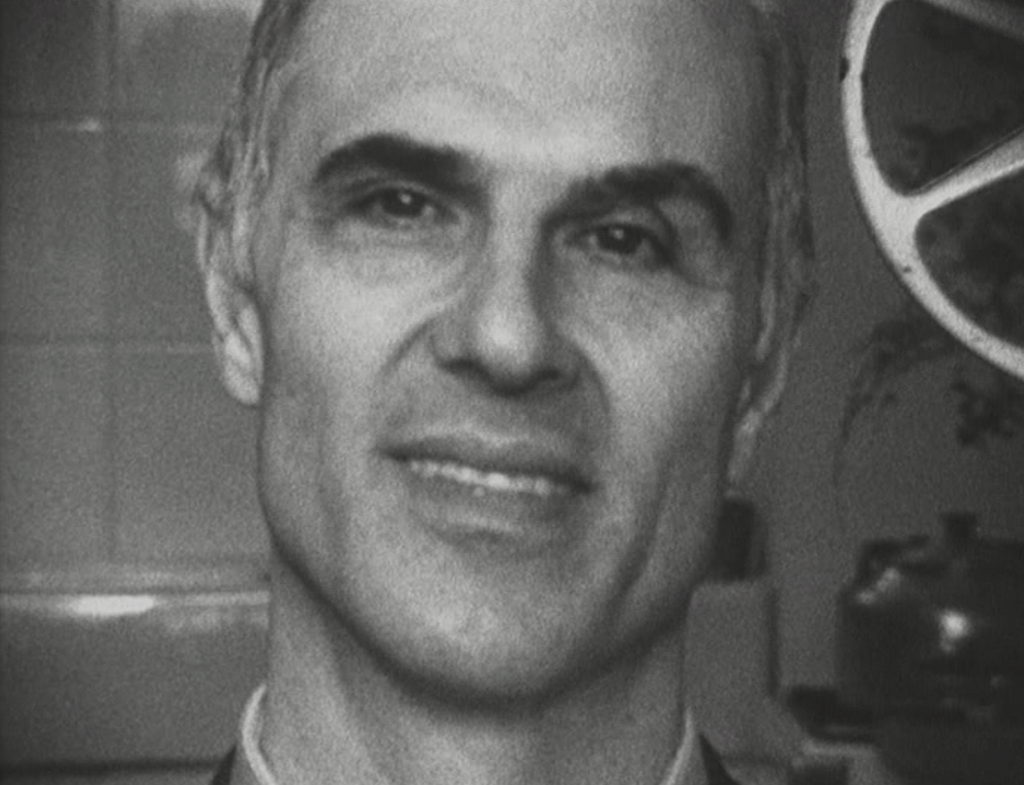

In Graf Zokan (Franz West) (1969), the celebrated artist squirms beneath the camera’s regard while banal elements such as a water spigot or an outdoor café table drift into view. The result is an exercise in worldly interruption.

Peter Kubelka and Jonas Mekas (1994) incorporates Gröller’s own presence. The aftermath of an argument with Kubelka becomes embedded in the air, shaping tensions and micro-expressions. Reconciliation unfolds wordlessly in a choreography of glances and hesitations.

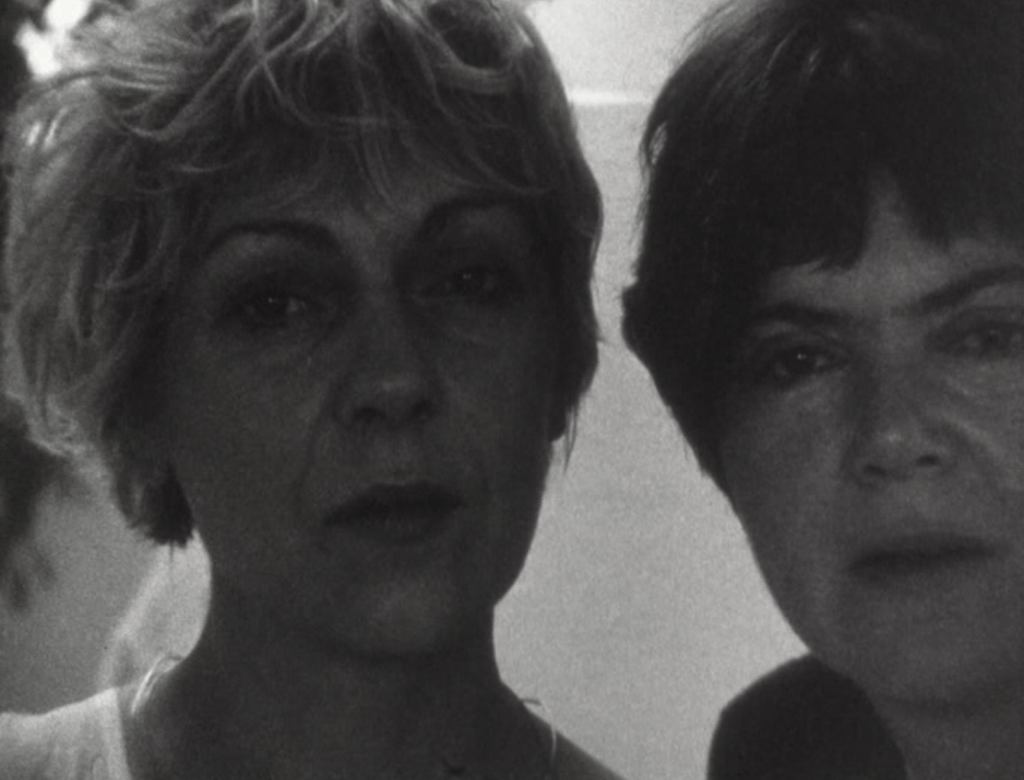

Eltern: Mutter, Vater (Parents: Mother, Father, 1997/99) confronts the difficulty of filming one’s parents. Her mother’s full-color restlessness and father’s monochrome indifference forge a valley between memory and attachment. Such are the asymmetries of familial bonds.

Lisa (2001) alternates between sternness and a sudden smile. Care and tension hover in unresolved harmony.

Polterabend (Hen Night, 2009), filmed the night before Gröller’s wedding, transforms a social ritual into a photographic event. The group portrait becomes a swarm of miniatures as guests step forward into the camera’s silent gaze.

Der Phototermin (Photo session, 2009) offers a moment of joy: a man and woman laughing while still and motion cameras capture them. Their silent laughter overflows with unmistakable warmth. The final reveal of the photographs grounds their exuberance in physical trace.

Gutes Ende (Bliss, 2011) devastates. Her mother, dying in a nursing home, can still sense her daughter’s presence. Gröller wipes the lens, an act of care that becomes part of the portrait, as if clearing the fog from the world’s surface so her mother can be seen. Another woman in the room is pregnant. Birth and death share the space without commentary.

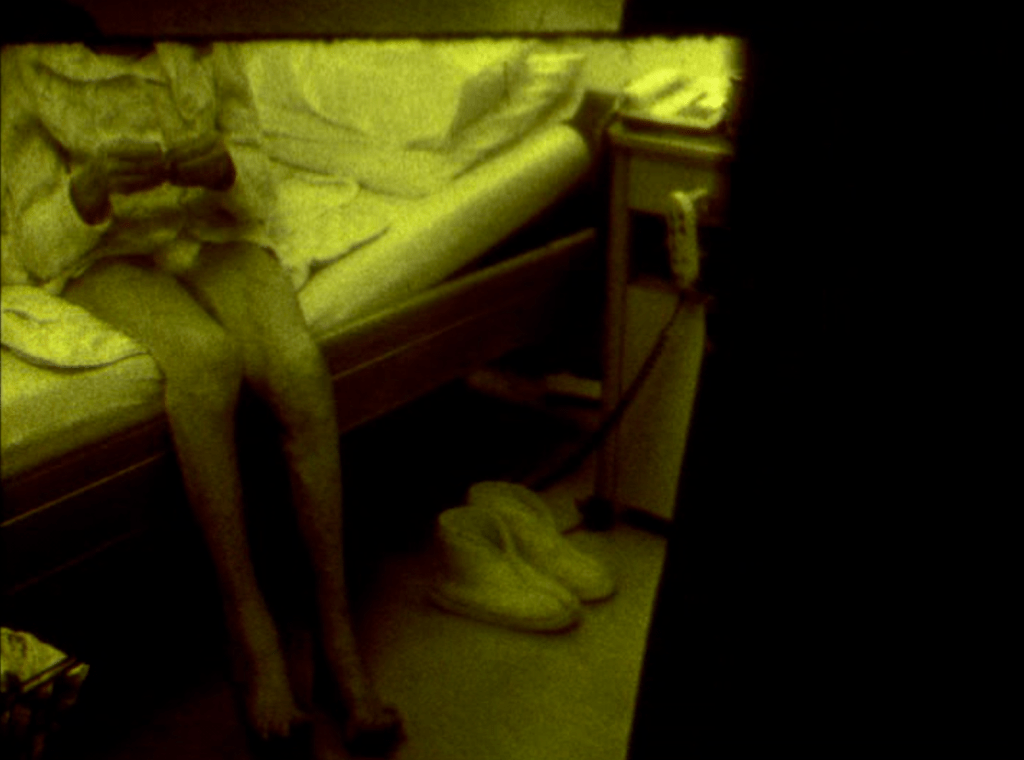

Ich auch, auch, ich auch (Me too, too, me too, 2012) turns inward. The jaundiced color, trembling voice, and wandering monologue form a self-portrait of illness, a body on the verge of dissolving into its own fragility.

Delphine de Oliveira (2009) layers past and present in what Harry Tomicek calls a “[p]aradox of portraits that insist upon their right to stay a mystery.” Ilse’s early image appears projected on a wall before the frame shifts to Delphine, who smokes and moves with the same withheld despair. She accepts an apple and returns it, an anorexic refusal that resonates with Ilse’s remembered presence.

La Baromètre / Laurent / Herachian (2004/05/07) observes three men who enter Gröller’s Paris apartment to watch her perform a striptease. Their reactions, ranging from arousal to awkwardness, become the real subjects. Vulnerability and power trade places.

Psychoanalyse ohne Ethik (Psychoanalysis without Ethics, 2005) stages an analytic encounter devoid of sound. The viewer must listen with their eyes as Gröller quietly peels away a cast from her leg. Therapy becomes a double removal: of protection and of façade.

Passage Briare (2009) shows a tentative romantic encounter. Two older people negotiate the camera’s presence and their own hesitant intimacy.

Spucken (Spitting, 2000) turns domestic mischief into portraiture. Gröller spits cherry pits at the camera. Childish, unruly, and undeniably endearing.

Boston Steamer (2009) moves into abjection. In a nod to Kurt Kren, defecation is filmed in extreme proximity through a cardboard aperture framing each anonymous anus. With each repetition, the grotesque takes on an unexpected tenderness.

Heidi Kim at the W Hong Kong Hotel (2010) studies architectural vulnerability. A woman perched on a windowsill dwarfs herself before the city’s scale.

La Cigarette (2011) brings five people, including two actors from Godard’s Nouvelle Vague, into a small room. A cigarette circulates like a fragile talisman. The woman who smokes collapses onto the table, and an old man attempts to revive her by offering the cigarette again. The gesture feels both horrific and healing.

Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 2006/11) is unusually fluid for Gröller. A morning-after scene, with pizza slices and soft sunlight, becomes a quiet celebration of friendship in its least performative state. She captures the residue of the night with affectionate precision.

Wherever she is in space and time, Gröller resists any urge to pry open her subjects. Instead, she constructs situations in which the revelation speaks in the dialect of the individual. Having built something like a counter-history of human appearance in which faces shift, seasons change, and bodies falter or revive, her gaze nevertheless retains a peculiar steadiness in recognition of the fact that the self revealed at any given moment is only a temporary tenant. The psychological thread linking her work is an awareness that identity is never entirely ours but something that contradicts itself at every turn. Her portraits do not crystallize a person so much as follow the fault lines along which each becomes someone else. What they ultimately disclose is not hidden emotion or buried truth but the simple fact that we are all in continuous negotiation with time. In this sense, her oeuvre gestures toward a philosophy of the unclaimed self that lives not in fixed expressions but in the fragile spaces between them. Such art invites us to meet that self, not with certainty but with care.