You walk into a large room. Dark, save for four glowing screens. The face on each is the same: singing, whispering, screaming in concert like some demonic slot machine. Moments are looped, locked in ephemeral chains by which inward structures blur into outward fruition. Bones and tendons cry for recognition, even as their pathos erodes with every false start. This process becomes more organic the more contrived it tries to be. At once algorithmic and unpredictable, it unfolds through the flesh of which it is made, shaping light into something audibly destructive. The light, in turn, molds images that are both alien and familiar. Sound unleashes shards of time in a torrent of disillusionment. The curtain falls, revealing a cavernous interior where resides the actor behind all our voices, that invisible artist of the soul whose only language is rupture.

This is what it feels like to experience Motion Control Modell 5 (1994-96), a digital video installation by Vienna-based artist duo Granular Synthesis. The face and voice in question belong to Japanese performance artist Akemi Takeya, whose passion for the project was integral to its becoming. By taking her otherwise continuous performance and splicing it into a rhythmic onslaught, melding the natural and the mechanical, Granular Synthesis—in both name and process—fragments the norms of synchronicity between sound and image. How does the body fit into, if not constitute, such an audiovisual world? What is its reality? Can sound and image exist in the absence of time, without bodies? In my attempts to address these questions, I take Modell 5 as a viewfinder to the complexities of flesh on screen, of one’s experience of that flesh, and of how both meet in the specific location of the gallery.

The museum installation blurs a contested boundary between image and sound. On the one hand, sound has, since the latter half of the twentieth century, become an increasingly prominent aspect of installations, imbuing them with an attraction to interactivity and multisensory engagement. One may also read indifference into the art form: the artist can set the space and run, leaving audiences to grapple with the results on their own terms. Whether or not such a situation can be considered musical would seem to hinge on its viability as a performance, on whether the piece conforms to basic expectations of gesture, sound production, and effect. Since the 1960s, artists have consistently emphasized, through the medium of video, our inability to determine where we begin or end. Their images configure the human body as a user of technology, as an extension of the technology being used, and even as a technology in and of itself—as in a musical performance, for which the body is figured not only “in” a sonic act but also “as” a sonic act. Its expressivity is self-transcendent.

The televisual body may be reconfigured in more ways than are possible by its inherent means. Technology enables artists to deconstruct the modal and figural language of moving images, thereby creating shadow plays of indeterminate originals and mimics of the quotidian from fresh and exciting perspectives. According to video artist Joan Truckenbrod (1992, 95), however, digital and computer technologies simply “offer artists the potential to convey the complexities of environmental, cultural and political issues by layering and choreographing images, text, voice and sound in a manner that parallels the fabric of contemporary life.” Taking this parallel to be true, what can we surmise about the continuity of contemporary life when its most topical representations are also the most fragmented? Does this mean that we, as children of deconstruction, are destined to eat off the cutting room floor? We seek confirmation of, if not refutation to, these concerns in arts of many stripes, only to discover that those same arts embrace both destruction and illusion of seamless existence. This is not a contradiction. Rather, it is the keystone in the arch of the creative spirit.

Mutability more than compatibility is of special significance in videographic life. It is what can be hidden or rejected in video rather than what can be visually mapped across reality proper that determines its effectiveness as an emotive art form. The screen overlooks more than it reveals, blurring the distinctions between inner and outer spaces through the interstitial bodies of its making. In light of this, Johannes Birringer (1999, 57) regards postmodern electronic media as “leaving no traces behind since they continuously simulate and reduplicate citations as such.” Yet, why should any medium, postmodern or not, leave no traces? Traces are, in fact, an inevitable result of bodily involvement. For whether or not artistic experience is hands- or eyes-on, one always finds within it the potential to speak and to be heard, to listen and to be felt. The body functions with a unified purpose as a means to achieve a desired result. In the context of performance, it is rudimentarily a productive, if not reproductive, entity insofar as it nourishes its audience, which may also consist of decidedly mechanical receptors (e.g., microphones).

We can, then, revise an assertion I have just made: The boundaries between inner and outer are not so much blurred in video as they are rendered coincidental. Any discomfort in that fact is due to an unwillingness to acknowledge the fundamental sonicity of our anatomies. Said boundaries are, as art historian Amelia Jones (2006, 136) might define them, “functions of videographic representation, as bodies produced through (apparently coextensive with) a screen, which thus takes on three-dimensionality as a kind of body.” And might not the body also become the screen? We are, after all, skin and veins, nerves and bone, brains and blood, all working to breathe rhythm into an audiovisually marked life. We fashion our instruments from the same molecular stuff—plucking, bowing, and striking them on the asymptotic path toward mastery of expression.

Following Jones, I should also like to ask: How do we experience our own flesh in relation to the flesh of sonic production? My answer: Musical flesh is self-sufficient and, when bound to videographic reality, its relationship to sound is already secured. As a representation of the real, it is its own reality, divorced from a corporeal original. Deleuze saw this already in his approach to the “virtual,” which for him always defined a reality at odds with its empirical counterpart (Hansen 2004, 43n), yet which, in so being reconfigured, empirical reality as an equally arbitrary state of defined existence. The very fact of a virtual reality’s existence configures it as a reality in and of itself, beyond the reductive grasp of teleological assumption. The excitement of video art stems from its propensity to combine “competing elements” in ways that draw attention to their discordance (Wood 2007, 142). And so, even as we take apart these images—these composites of illusion, loop, and glitch—piece by piece, they continue to cry, All at once!

Here I move away from the fatalistic assumption of video artist Vito Acconci, who describes his medium as “a rehearsal for the time when human beings no longer need to have bodies” (cited in Birringer 1999, 69). Can the scenario Acconci describes not also be an affirmation of the body? Can it not, by its very nature, celebrate the body in ways not sexually, racially, or classically demeaning? This is the promise offered in the soundness of video, which seeks the “radical transformation of art and society” (62), yet continues to operate within and of society. To be sure, the work of artists such as Bill Viola and Mara Matuschka has challenged bodily norms through the use of technological innovation. In this sense, “installation art can be seen as an evolving process, no longer a static object, but as a work that unfolds in relation to both the viewer and its location” (Wood 2007, 134). The process itself is clearly physiological—hence “body” of work—insofar as it evolves. By the same token, we might, then, wonder how this is any different from the reality of a “static” museum piece. Video art bears differentiating not through its separation from art but through a shared connection to art through sound. A sculpture may hum, but a video sings.

To see the image as material is not to objectify it, but rather to acknowledge its place in the world. Video is performance-oriented at heart, embodying musicality even in the seeming absence thereof. The influence of performance practices on the development of the televisual arts is incalculable. In acknowledging this influence, we come to see video as a means of intimacy, as it inherits an ongoing interest in its own materiality and real-time manipulation of images from key figures such as Nam June Paik and Steina Vasulka, both of whom come from musical backgrounds (Salter 2010, 116). Paik’s training in music composition and performance was especially vital to his development of video as a medium. Consequently, his brilliance came less from what he did to change the medium and more from what he did to foreground its vibrational constitution. Lest we incorrectly file Paik away in a drawer labeled “Essentialism,” let us look at an example.

In the 1963 installation piece Symphony for 20 Rooms, Paik filled his eponymous rooms with all manner of noisemaking objects, including prepared pianos and treated violins, as well as “a scattering of thirteen television sets that, as Paik later described, ‘suffered 13 sorts of technical variation’” (ibid., 117). Paik’s choice of the word “symphony” was far from arbitrary. While it did retain the metaphorical sense of comingling, it also implied a visually commanding performance space and musical event. In the latter vein, Paik’s room of distorted television sets was not unlike a prepared piano in exploded form. As “musical instruments subjected to the nondeterministic force of electronic signals,” the sets fit snugly in line with the John Cagean idea of preparation (ibid.). Paik was trying to show that video was itself an instrument to be played.

In the work of Austrian artist Kurt Hentschläger and German-born Ulf Langheinrich, who formed the collaborative project Granular Synthesis in 1991, I observe a homologous process at work. Their collaborations simultaneously exemplify and transcend postmodern currency, opting instead for something far more regressive and introspective. The Granular Synthesis moniker is purely descriptive, referencing the process by which large acoustic events are generated from myriad “sonic grains” (Roads 1988, 11), a process that unifies sound and image. It looks at itself in the mirror and revels in the possibilities. In this respect, Granular Synthesis makes no mistakes about its indebtedness to Paik.

The unity exemplified by Granular Synthesis sees more than what bodies appear to be. As vessels for prayers for the unbroken, televisual bodies take on what Maria Chatzichristodoulou (a.k.a. Maria X) and Rachel Zerihan call a “myriad aesthetic” (Chatzichristodoulou and Zerihan 2009, 1). This aesthetic presupposes an acceptance of creation under a matter cannot be destroyed principle. It also embraces a key binary. On the one hand, we are all composed of the same sounds, while on the other, we are so clearly different from one another, if not also from ourselves, that to subscribe to the romantic notion of a Universal Lyre is to tie a noose around philosophical resolve. Granular Synthesis portrays this most clearly in Modell 5. Using 4-channel video as its medium, the duo concretizes its synthetic approach to the human form on a fresh plane of vividness. For purposes of this discussion, I focus on two key aspects of Modell 5: first, its playful troubling of interactivity; second, its musicality.

Modell 5 renders us lulled, if sometimes confronted, over the course of its 45-minute becoming. Using video recordings of the head, face, and voice of Akemi Takeya, the duo designed a system whereby her expressive vocal improvisations were “severely stylized” by looping and rearranging snippets of time (i.e., “grains”) into mathematically determined sequences that defy the trappings of temporality. The result sounds like a skipping CD, synced with its visual equivalent. Any performance forges its own pathos, refracting temporal concerns along caesuras of self-discovery. In such “mediatized” performance, says Philip Auslander (2006, 9), “the crucial relationship is not the one between the document and the performance but the one between the document and its audience.” As such, “the authenticity of the performance document resides in its relationship to its beholder rather than an ostensibly originary event.” In short, “its authority is phenomenological rather than ontological.” Seeing the document itself as a performance, therefore, allows us to experience the synthesis of Modell 5 for (and within) ourselves. This distinction further pushes the line between liveness and the medium of musical transmission, whereby the very notions of integration and interaction are rendered synonymous (Jeffereis 2009, 199). I question, however, the special interactivity of the form, for according to Lev Manovich (2001, 56), new media art forms are no more interactive than classical forms. Both are live, if not living, by virtue of their phenomenological display. They are presences to be experienced.

Philosopher Laird Addis (2004, 175-176) posits five types of knowledge in relation to music: knowledge “for,” knowledge “from,” knowledge “that,” knowledge “how,” and knowledge “of.” Modell 5 activates all of these, and more: the “for” through Takeya’s interest in the project concept and its manifestations; the “from” through her collaboration with Granular Synthesis to make those manifestations a reality; the “that” through the installation space itself; the “how”through her improvisational prowess and Granular Synthesis’s technical acuity; and the “of”through the experience of live audiences. Although not quite on the level of a Gesamtkunstwerk, it nevertheless evokes the distributive power of an opera, with scenography and soloist locked beyond space. We may read into it recitatives, arias, mad scenes, and other catharses against a blank scrim, its stage never seen and its story undeniably aleatory: “In a double transformation, both in replacing the human form of the actor that occupied the space in front of the screen onto the screen itself and the human performing in front of the camera, the reassembled, projected body that reemerges in the performance reaches its machine-age apotheosis” (Salter 2010, 164). Yet again, the projected body always seems secondary, derivative, and interred in a sea of pixilated information where every continuity break laps a new wave along a resonant shore.

Through a deft phase drifting technique, the image converses with itself in a wash. At once prayerful and violent, it careens through the ether with the stealth of a radio wave, visualizing the body’s multiplicity in screen-centric performance. To achieve this effect, Granular Synthesis employed an Avid online system, by which Takeya underwent what Chris Salter calls “a real-time Francis Bacon” (ibid., 175), only where Bacon captures moments of rupture in the stasis of the painted image, here the rupture is multiple, flailing, and rhythmic. The facial close-up is not a “liberation of affect from the body” but an “interface between the domain of information (the digital) and embodied human experience” (Hansen 2004, 134). Not a severance but a humble, if not humbling, regard. As we find ourselves lost in Takeya’s singing visage, we are also lost in her agency, capable as it is of what we are not.

It is in this sense that Salter (2010, 175) further characterizes Modell 5 as “a step toward electronic possession, where image and sound, screen and flesh, matter and pixels were pushed to degree zero.” Just what is this “degree zero”? Is it death? Does life end where the image stops? Surely not. Video is a medium with an afterlife, for not only is the body possessed, but so too is sound, specifically in the form of the voice. In his essay, “The Grain of the Voice,” Barthes unravels this theoretical thread, asserting that language fails when it comes to interpreting music precisely because language is, in itself, a form of music. Yet, somehow music, as an act in and of itself, fails far less often when it comes to interpreting language. “Music, by natural bent,” he writes, “is that which at once receives an adjective” (Barthes 1977, 179). As such, it is a sign without an identity, a self-protecting subject whose very description acts as armor. For Barthes, in the context of vocal music—and here he is speaking of German and French art songs—the “grain” of the voice, the “materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue” (182), has a “dual posture, a dual production…of language and music” (181). By thus breaking the voice down to both its literal and theoretical grain, Granular Synthesis puts the music of Modell 5 through the wringer of communication.

Modell 5 is a pragmatic work, if only because its methods are far from hidden. Still, there is something beyond text and music, something undeniably somatic, in the singing. Just as deaths sung on the operatic stage are so often excessive, so too is the song of Modell 5 recessive. The excess is that which is lacking: namely, the ability to refract and displace the body on its own terms. I should therefore like to remove the quotation marks with which Barthes couches the word “grain” in favor of its literal significance as the materiality of the music. The grain is no mere metaphor, but a correct acknowledgment of the voice as a vibrational matrix of the tangible and the abstract.

Much in the same way that Timothy Murray (2000) argues for the materiality of interactive performance, even in the most digital of realms, so too does the voice of Modell 5 take shape in the molecules of the space it inhabits. Thus, it is a plastic, moldable form that allows the potential player to transcend those very concerns. The ontology of the voice is disparate from its source. It is a resurrected source in the light of its confirmation through repetition. In the words of Tom Sherman (1998), Modell 5 is a “perpetual moment machine.” By looking past the causal relationship, this characterization gets to the heart of the piece: perception as recapitulation. The screen, then, “is not simply a way into a story-world, document, game, or artwork, but an interface which…intercedes with the way in which a viewer gains access to the story-world, document, and so forth. The interface can be seen as being created by elements that work to organize a viewer’s attention” (Wood 2007, 5).

The screen is nothing more than itself, and when multiplied, becomes neither a window nor a mirror, but rather a node in a network (cf. Jones 2006, 134, citing Jean Baudrillard). In Modell 5, the interface is one step removed. More precisely, it complicates the dynamics of the interface by drawing attention to itself through the very act of being noticed. We experience in its grotesqueness something profoundly shared. Through the work’s relentless visual and sonic staccato, we see and hear the body for the first time. Where only linear articulation was possible before, now it is shattered in favor of overwhelming disclosure.

But how do we reckon the above impulses when devoid of human anchorage? Such is the question addressed by Reset, another video installation from Granular Synthesis that brings us into an even deeper communion with our relationship to the almighty screen. To enter it is to step sideways—out of linear time, out of the comfortable frameworks by which we ordinarily tame the visual, and into a pulsing interval where images behave less like representations and more like events. The work loops from two synchronized DVD players, each feeding its own projection onto opposite walls, creating a chamber of reciprocating light. Originally conceived for the Austrian Pavilion at the 2001 Venice Biennale, this installation becomes less a room and more a breathing organism, one whose inhalations and exhalations are made visible through shifting textures, oscillations, and the shimmer of self-authored algorithms.

Granular Synthesis built the piece using software of their own making—a decision that registers not merely as technical innovation but as a philosophical gesture. The artists refuse to let commercial tools mediate the birth of their imagery. Instead, they craft a digital womb, an autonomous system from which the piece can emerge with its own logic, its own metabolism. In doing so, they confront the viewer with a question: What happens when images are not captured, but generated? What becomes of vision when its source is no longer the camera’s lens, but a computational pulse?

Langheinrich describes the result as “an increasingly oscillating space of light, not abstract in the actual sense of the word but gradually emptying.” And indeed, as one watches, the space seems to hollow itself out. The projections thicken and thin like fog, sometimes palpable, sometimes fugitive, always sliding between presence and disappearance. The haptic effect—the sense that the image presses itself against the surface of your skin—is unmistakable. It is vision turned tactile, light turning into a kind of climate.

Standing in the installation, you are surrounded by a visual language that seems to have escaped the confines of its alphabet. The imagery resembles a minimalized sound visualizer, a cousin of those trembling frequency spectrums that have danced in the peripheries of clubs and laptop screens. Yet here the language is slowed, purified, withdrawn from spectacle. What remains is the rhythm of perception itself—a meditation on how the mind processes flicker, repetition, and the tiny fractures between frames.

Gaspar Noé would later appropriate a similar technique for his title sequences, draping his films in strobing introductions that hint at the chaos to come. But where Noé uses the method as a violent overture, Granular Synthesis brings it into a different register: quieter, more intimate, more attuned to the devastating beauty that arises when the retina is allowed to dream. The sensations here are haunting not because they threaten, but because they insist on a way of seeing that bypasses narrative entirely.

In many ways, Reset takes the conceptual DNA of Modell 5 and folds it inward. The latter, with its amplified gestures and explosive multiplicities, feels like an externalization of the digital psyche. Reset, by contrast, turns that psyche into a sanctuary. It is as if the raw materials of perception have retreated into themselves, seeking not to overwhelm. The result is a form of intimacy born from the proximity of light to surface, of sound to vibration, of the viewer’s presence to the room’s shifting architecture.

By the time the loop restarts—and it will restart, always—you realize the title is not merely descriptive. Reset becomes an instruction, a mantra, an invitation to clear the perceptual field and begin again. Each repetition is both return and renewal, an oscillation mirroring the work’s own play of fullness and emptiness. In this sense, the installation does not conclude; it continues. It continues long after you’ve stepped back into the known world, its flicker lingering like an afterimage on the inner eyelid, reminding you that seeing is never merely optical but is, in its most profound moments, an act of surrender.

With the advent of DVDJs, granulation has fully entered the concert space as an acceptable mode of performance. Through the styling of young practitioners like Mike Relm, who has gained a reputation for his live scratches of viral hits and remixes of popular film, the manipulation of synchronous image and sound has breathed old life into the new. Exciting about Relm’s work in particular is the audacity of its sampling, for in his work we have not only the familiar in sound spliced and reworked before our ears, but also the familiar in images redeployed before our eyes.

Common to the work of both Relm and Granular Synthesis is the edit, which, rather than manipulating audiovisual information, treats its elements as pure cells of connective mastery. But is there mastery in the Granular Synthesis approach? Perhaps the question is moot, for if “even the most ordinary images find their value, their substance, their impetus, in the agency and investments of our flesh” (cited in Jones 2006, xiii), then we cannot possibly shackle Takeya’s sheer vocal presence as anything less than a concerted act. What separates Modell 5 from the spectacle of its installation is precisely its camouflage of mastery. Somewhere in its denouement hangs the uncanny, trembling skeleton on which every act of reception is fleshed.

If such interventions appear violent, it is only because we recognize the possibility of violence in them. Although blatantly expressed via Takeya’s bleating cineseizures, division forces its way into even the most ponderous moments of the Modell 5 experience. In this vein, Addis (2004, 189) notes an ontological affinity between sound and consciousness whereby the question of time is freed from the obligation of change, and is instead tied biologically to affect (Varela 1999, 295-298). We cannot, then, collapse the Granular Synthesis gesture into a chronological narrative, nor can we promise the comfort of innovation despite the complexities described above. It is the programmability of media that makes it new (Manovich 2001, 27), not necessarily what is being programmed. The videographic experience cleanses residue left by the messiness of thought and action, leaving us to face the “transparent eternity of the unreal” (Blanchot 1989, 255). Imag(in)ing such anatomies gives credence to coincidence as a way of life. The anatomies of Modell 5 are not new. They are resoundingly infinite.

References

Addis, Laird. 2004. “Music and Knowledge.” In Truth, Rationality, Cognition, and Music: Proceedings of the Seventh International Colloquium on Cognitive Science, eds. K. Korta and J.M. Larrazabal, 175-190. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Auslander, Philip. 2006. “The Performativity of Performance Documentation.” Performing Arts Journal 28 (3), 1-10.

Barthes, Roland. 1977. “The Grain of the Voice.” In Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath, 179-189. New York: Hill and Wang.

Birringer, Johannes. 1999. “Contemporary Performance/Technology.” Theatre Journal 51 (4), 361-381.

Birringer, J. 1991. “Video Art/Performance: A Border Theory.” Performing Arts Journal 13 (3), 54-84.

Blanchot, Maurice. 1989. The Space of Literature. Translated by Ann Smock. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Chatzichristodoulou, Maria, and Rachel Zerihan. 2009. Introduction. In Interfaces of Performance, eds. M. Chatzichristodoulou, et al., 1-5. Farnham, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Hansen, Mark B. N. 2004. New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

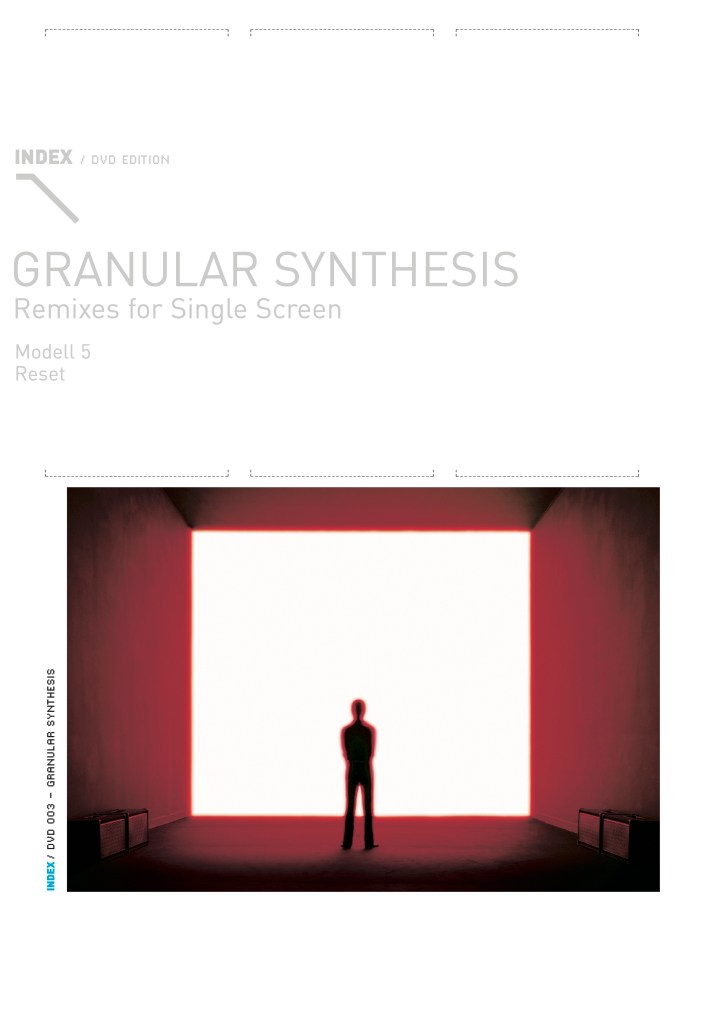

Hentschläger, Kurt, and Ulf Langheinrich. 2010. Granular Synthesis: Remixes for Single Screen. DVD. Vienna: Arge Index.

Jefferies, Janis. 2009. “Conclusion.” In Interfaces of Performance, eds. M. Chatzichristodoulou, et al., 199-202. Farnham, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Jones, Amelia. 2006. Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject. London and New York: Routledge.

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Murray, Timothy. 2000. “Digital Incompossibility: Cruising the Aesthetic Haze of the New Media.” Ctheory, http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=121 (accessed 13 April 2012).

Roads, Curtis. 1988. “Introduction to Granular Synthesis.” Computer Music Journal 12 (2): 11-13.

Salter, Chris. 2010. Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Sherman, Tom. 1998. Granular Synthesis press release. Media Art Net. Accessed 15 June 2014. http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/modell-5/

Truckenbrod, Joan. 1992. “Integrated Creativity: Transcending the Boundaries of Visual Art, Music and Literature.” Leonardo Music Journal 2 (1): 89-95.

Varela, Francisco. 1999. “The Specious Present: A Neurophenomenology of Time Consciousness.” In Naturalizing Phenomenology: Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science, eds. J. Peitot, et al., 266-312. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Wood, Aylish. 2007. Digital Encounters. London and New York: Routledge.