Behind the films collected on NOT HOME lies an inquiry into the act of seeing, shaped by the unsettling realization that vision is never objective or neutral. To witness the world through images one did not make is to inherit the desires, omissions, and vulnerabilities of subjective strangers. Having long worked as a cartographer of found memory, Gustav Deutsch finds himself in the more elusive position of a traveler who never arrives, someone perpetually foreign even in the intimacy of his own gaze. What does it mean to be the custodian of other people’s looking, and what is revealed when the world is glimpsed through perspectives that cannot be fully assimilated?

Adria – Holiday Films 1954-68 (School of Seeing I) lays track by presenting postwar tourist films as if they were relics of some vanished civilization. Its structure moves from still shots to views from vehicles to montages in motion, a transition from the fixed monumentality of place to the restlessness of those attempting to inhabit it. Signs, oceans, bridges, cars, beaches, and faces gather into a quiet taxonomy of yearning. These fragments carry an ache, as if time had already begun erasing them during the very moment of their recording. The Venice passage becomes a kind of primal scene: a man serenades us on the rising waters, yet we hear nothing. Expression survives only as the ghost of a gesture. Those cradled in frame are almost certainly gone, their vitality preserved in an archive that cares nothing for mortality. Deutsch teases out this paradox—that these films were meant to enshrine happiness yet now mirror the fragility of all that once felt permanent—with painful clarity.

Eyewitnesses in Foreign Countries (1993), made with Moroccan filmmaker Mostafa Tabbou, turns Deutsch into a documented outsider. Six hundred shots, each lasting three seconds, alternate between Figuig and Vienna in a steady, metronomic rhythm. Deutsch’s astonishment at the desert’s elemental force contrasts with Tabbou’s measured attention to the textures of European daily life. The exchange is not symmetrical, the time limit suggesting a fragile equality at best. Deutsch cannot entirely escape the exoticizing pull of unfamiliar territory, while Tabbou renders Vienna without spectacle, letting human detail eclipse architectural bravado.

Notes and Sketches I (2005-15) extends this sensitivity across a decade of small observations. Thirty-one pocket films made with digital cameras and mobile phones emerge as devotional gestures spared from the erosion of ordinary time. The lazy Susan sequence in a restaurant becomes a center of gravity around which an entire perceptual world turns. Plates glide, voices hum, the table rotates, and from this dance an unexpected sanity arises. Sound plays an equal role in these pieces. Spaces speak their own grammar, and Deutsch listens carefully, letting ambient noise shape the contours of each entry. Geography dissolves; what remains is an atlas of attentiveness. These sketches reveal how the unguarded instant often contains more truth than the composed event. They show how perception, when freed from the demand to explain, allows the world to declare its own quiet coherences.

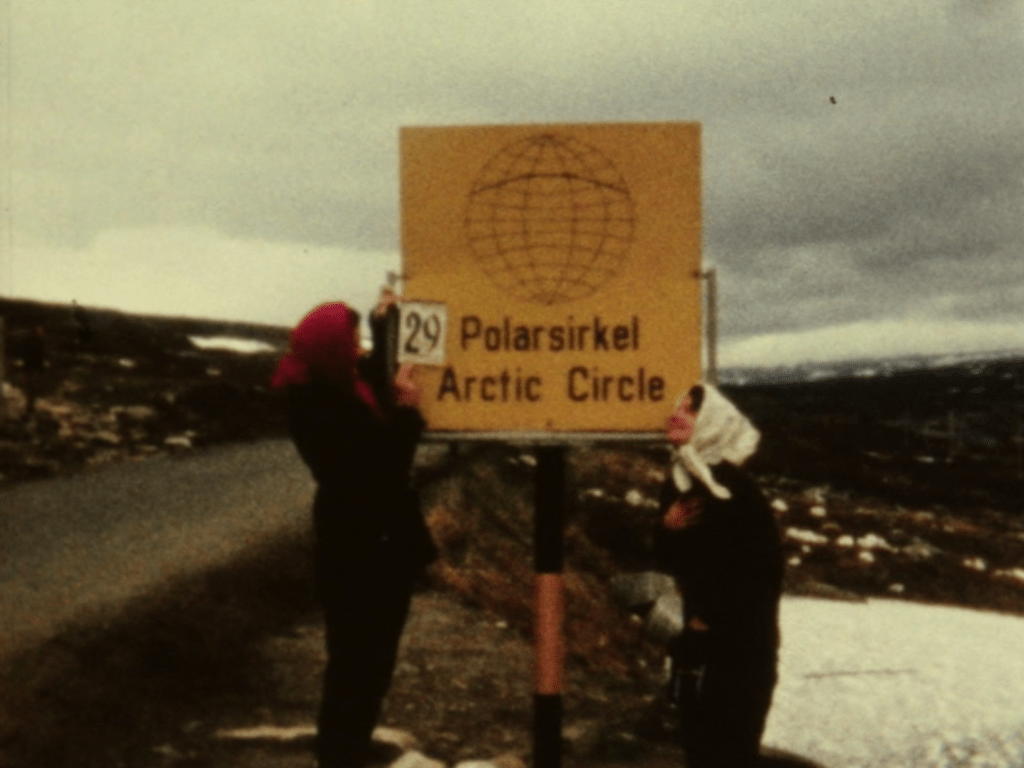

The bonus film, Sat., 29th of June / Arctic Circle (1990), operates as an early crystallization of the larger project. Four travelers pause at the titular location, pose with numbers, and mark their presence as if the boundary they have crossed holds metaphysical weight. Their actions, unconsciously choreographed, are as sincere as they are awkward, unaware that decades later they will be observed as part of an experiment in temporal distance. What they enact is the desire to extract meaning from place, to position one’s own frailty against the indifference of all terrain.

Across these works, Deutsch drifts between ethnographer and wanderer, historian and poet. He gathers glimpses rather than conclusions, tracing the shape of experience without feigning to contain it. And so, the foreign is never simply elsewhere. It appears whenever an image survives the life that produced it. It appears whenever we see ourselves reflected in the gaze of someone we have never met. And it appears whenever the world, in its fleeting instants, reveals that regard is always cyclical.