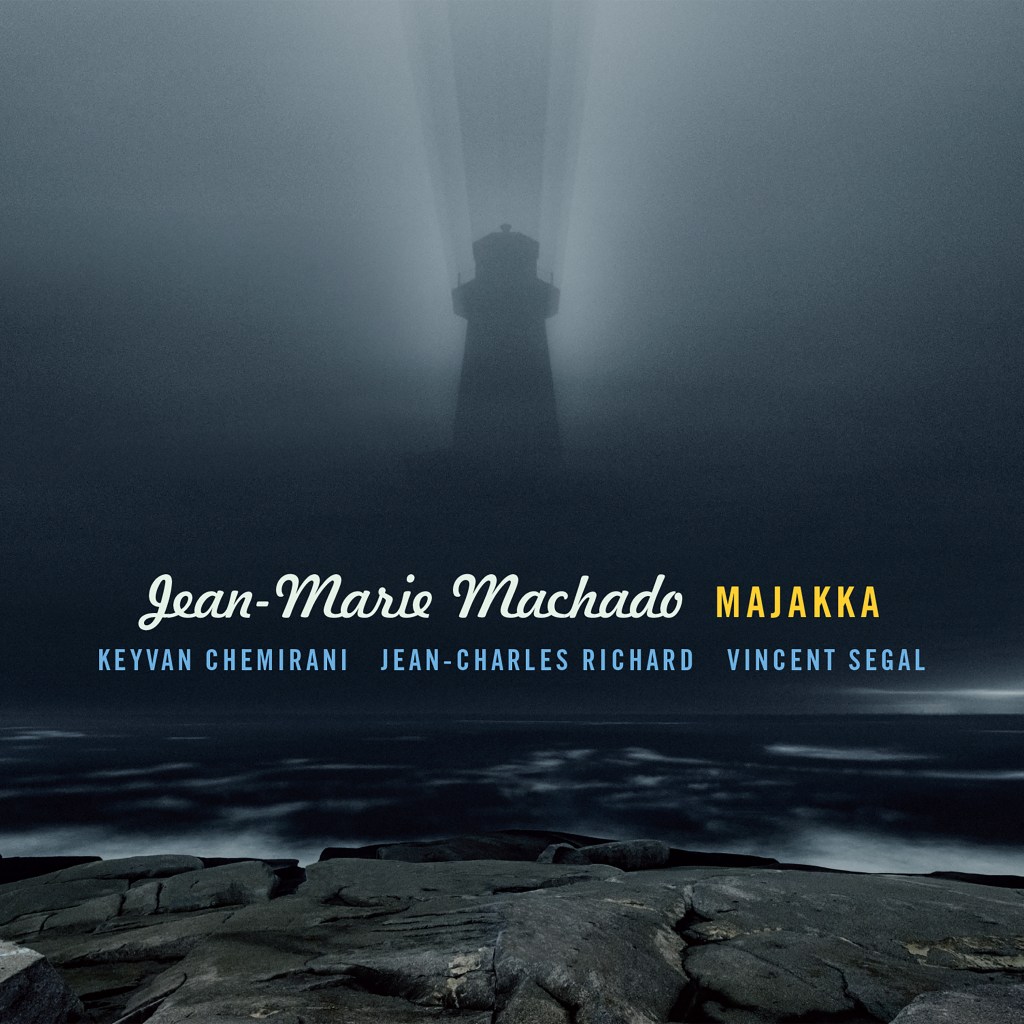

Jean-Marie Machado piano

Keyvan Chemirani zarb, percussion

Jean-Charles Richard saxophones, flutes

Vincent Segal cello

Recording, mixing, mastering Studios La Buissonne, Pernes-les-Fontaines, France

Recorded September 23-25, 2020, and mixed by Gérard de Haro, assisted by Matteo Fontaine

Mastered by Nicolas Baillard at La Buissonne Mastering Studios

Piano preparation and tuning by Sylvain Charles

Produced by Cantabile, Gérard de Haro with RJAL for La Buissonne

Release date: February 5, 2021

On Majakka, a word that in Finnish means lighthouse yet also suggests an inner watchtower, pianist and composer Jean-Marie Machado establishes a roaming state of mind. The album feels like a journey that refuses checkpoints, a music that travels because it knows nothing else. It charts the migration of memory, the drift of identity, and the strange geography of listening itself.

Throughout, Machado speaks of looking back at his own past recordings and discovering a color that had been waiting for him all along, a private illumination that insisted on being seen. That realization becomes the emotional compass of the album. Majakka is less a retrospective than a return that keeps going forward, a circular voyage where the act of remembering becomes another form of departure.

Surrounded by a remarkable ensemble, he shapes this odyssey with great subtlety. Keyvan Chemirani’s zarb (or tombak), a heartbeat of wood and skin, brings a tactile, breathing pulse. Jean-Charles Richard’s saxophones and flutes cut lines through the air like invisible routes, while Vincent Segal’s cello adds gravity, warmth, and a kind of traveling shadow beneath the light. Together they constitute a terrain that is constantly shifting, constantly unfolding.

Born into Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese lineages and raised in Morocco, Machado carries a passport made of histories rather than nations. His affinity for Brazilian music and for the impressionistic expanses of Manuel de Falla and others is his natural climate.

“Bolinha” opens with a sound that feels newly discovered even as it seems traditional. The zarb skims the surface of the music, giving gentle traction to the piano, bass, and saxophone as though the rhythm were lightly tugging the travelers onward. Beneath the beauty lies a quiet insistence, a pulse that suggests inward as much as outward motion. One senses that this journey begins by turning inside before it ever reaches the horizon.

In “Um vento leve,” the wind grows brighter, but longing deepens. Piano and soprano sax converse with tenderness while the rhythm section moves with guarded wisdom, keeping secrets until the landscape demands them. The music carries an ache for destinations that may not exist except in the act of seeking.

Both pieces belong to La main des saisons, a project inspired by Fernando Pessoa, whose poetry itself is a labyrinth of wandering selves. Later, “Emoção de alegria” returns to this spirit, dancing sideways rather than straight ahead. It refuses linear passage, opting instead for meandering revelation. The joy here is full of shadows.

“La lune dans la lumière” pauses the expedition. Cello and low flute circle the piano in a nocturnal embrace, creating a sound at once intimate and distant. The moonlight seems to hover rather than shine, illuminating sorrow without dissolving it. For a moment, travel becomes stillness, and stillness becomes its own destination.

“Gallop impulse,” first heard on Machado’s 2018 Gallop Songs, arrives like a sudden clearing after nightfall. Born from his connection with Chemirani, and colored by Machado’s earlier collaboration with Naná Vasconcelos, the piece blooms into immediate life. Percussion slips in and out of view, shaping the space around it.

The trio of pieces written for the quartet in the studio, “Les pierres noires,” “Outra Terra,” and “La mer des pluies,” carries the tremor of a pandemic-afflicted world. They feel carved from isolation, shaped by a time when itineracy felt forbidden. Yet within that restriction, Machado finds expansive imagination. The latter piece, a solo piano ballad, stands apart like a private confession. Its beauty is spare, unadorned, and devastating. It tells a wordless story of hunger for air, light, and meaning beyond the body’s limits.

“Les yeux de Tangati,” originally conceived for a duet with Dave Liebman, brings the journey back to earth and breath. Wooden flute (perhaps a nay?) and soprano saxophone weave across an imagined desert, while piano and pizzicato cello plant delicate footprints in the sand. A conversation with landscape itself, as though the dunes were speaking back. Finally, “Slow bird” lifts the listener into quiet enchantment, moving with restrained grace before opening into a surging release.

By the end, travel no longer feels like crossing from here to there. It becomes a way of being. Machado’s lighthouse does not guide ships to land but teaches them how to drift with purpose. The album suggests that borders are simply habits of hearing, lines we draw because we are afraid of the open.

And so, Majakka proposes a gentler philosophy. To journey is not to arrive, to belong is not to stay, and to remember is not to return but to keep moving with deeper awareness. The true horizon is not a place but a practice, the quiet art of listening while in motion, forever and without frontiers.