Gidon Kremer

Songs of Fate

Gidon Kremer violin

Vida Miknevičiūtė soprano

Magdalena Ceple violoncello

Andrei Pushkarev vibraphone

Kremerata Baltica

Weinberg/Kuprevičius

Recorded July 2019

Plokštelių studija, Vilnius

Engineers: Vilius Keras and Aleksandra Kerienė

Šerkšnytė/Jančevskis

Concert recording July 2022

Pfarrkirche, Lockenhaus

Engineer: Peter Laenger

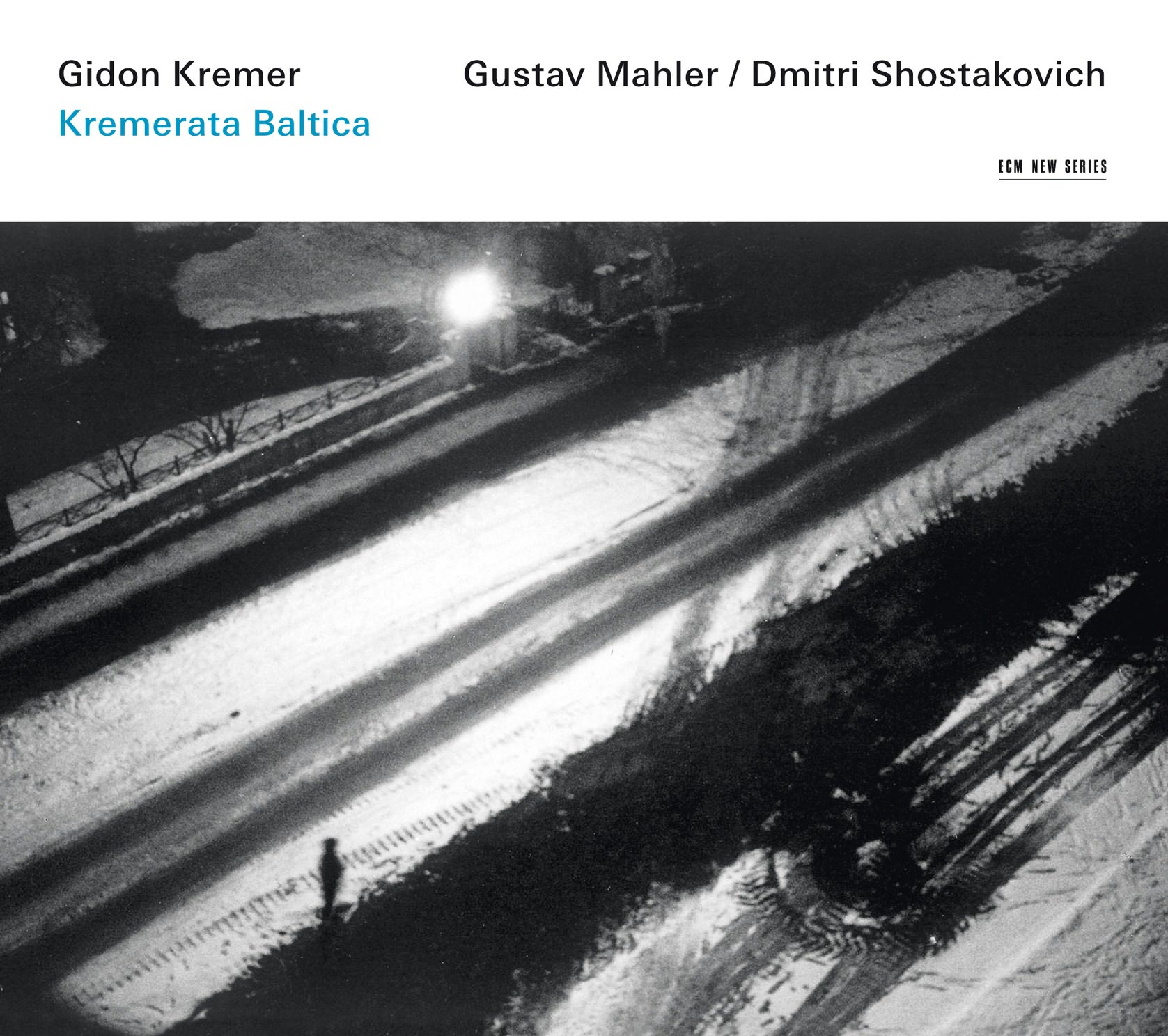

Cover photo: Thomas Wunsch

Album produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: January 19, 2024

The word fate comes from the Proto-Indo-European root meaning “to speak, tell, say.” In its Latinate forms, it took on the nuance of that which was spoken by the divine. Both senses give us doorways into the present disc, in which Gidom Kremer leads his Kremerata Baltica through the works of Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996) by way of living composers from the Baltic states. “This program,” Kremer notes, not coincidentally, “is meant to speak to everybody, reminding us of tragic fates along the way and that we each have a ‘voice’ that deserves to be heard and listened to.” In his brilliant liner notes, Wolfgang Sandner speaks of Kremer as an artist of multiple voices, having a “Jewish first name, German surname, Swedish ancestors, Latvian birthplace, three mother tongues, a love of Russian culture, and an imposed Soviet socialization.” And yet, these categories, he observes, dissolve the moment we utter them, for they are creatively inferior to the music that constantly defines (and redefines) the violinist and conductor’s sense of self.

For the past decade, Kremer has been a fervent champion for Weinberg via ECM (see, most recently, his traversal of the solo violin sonatas). Now, he reveals more obscure works by the Polish composer whose fragmentary yet coherent identity mirrors the interpreter’s own. From the dream-laden Nocturne (1948/49), arranged by Andrei Pushkarev for violin and string orchestra, to the dancing Kujawiak (1952) for violin and orchestra, a tapestry of sounds and textures blesses the ears. Between them are the tempered joys of Aria, op. 9 (1942), for string quartet, and three selections from Jewish Songs, op. 13 (1943), for soprano and string orchestra, on Yiddish poems by Yitskhok Leybush Peretz. The latter, originally published as Children’s Songs to avoid Soviet detection during the war, constitute a moving picture of thought, life, and action translated through the weakness of the flesh. Soprano Vida Miknevičiūtė navigates their pathways—by turns folkish and dramatic—as a needle in the dark.

Giedrius Kuprevičius (*1944) yields an equally substantial sequence bookended by two movements from his chamber symphony, The Star of David. The Postlude thereof is a duet between Miknevičiūtė and Kremer, in which David’s mourning for Saul and Jonathan funnels itself into introspection, connecting and gathering the soul. Between them are two refractions of the Kaddish, or Jewish prayer for the dead. In both, the mood implodes even as the heart struggles to contain every last molecule of sadness.

Before all this, we begin with the tremors of This too shall pass (2021) for violin, violoncello, vibraphone and string orchestra by Raminta Šerkšnytė (*1975). In listening (and we mustlisten) to Kremer’s lone voice emerging from an expanse that threatens to swallow us whole, we find cellist Magdalena Ceple joining not as an ally or hero but as a fellow questioner, one who throws kindling of doubt into the fireplace of mortality. Vibraphonist Andrei Pushkarev speaks of snow at first but soon reveals the language to be that of ice, thin and prone to breaking should one dare to overstep. By the time the orchestra shines its light, Kremer’s recitative has already laid bare the foundations of a story dislocated by memory. The world tries desperately to lock it into place, but it refuses—not through violent resistance but through the peace that comes from knowing who one is.

Concluding this fiercely intimate mosaic is Lignum (2017) by Jēkabs Jančevskis (*1992). Scored for string orchestra, svilpaunieki (ocarinas), chimes and wind chimes, it bids us to listen again, no longer to the instruments themselves but to the materials of which they are made. The violin’s dissonant entrance is the friction of leaves in an orchestral forest. Much like Erkki-Sven Tüür’s architectonics, Jančevskis looks to nature as a source of internal dialogue. As chimes grace our periphery just beyond the treeline, he reminds us that every word lost to the wind has a place to return to.