The collaborations between Mara Mattuschka and choreographer Chris Haring unfold in what Mattuschka calls an “inner time,” a realm in which duration is elastic, language unreliable, and form caught between its own imperatives and the pressures of cultural inscription. These darkly comic and disturbingly intimate films speak a vocabulary of incomplete sentences, glitched vocalizations, uncanny gestures, and bodies imitating their own existence. The effect is that of an audiovisual terrain in which identity becomes a form of atmospheric drift rather than a stable category, and every movement, no matter how spastic or hesitant, registers as both confession and critique.

Part Time Heroes (2007), shot in an empty Viennese department store, places performers Stephanie Cumming, Ulrika Kinn Swensson, Johnny Schoofs, and Giovanni Scarcella inside a maze of dressing rooms, the kind of liminal cubicles where self-presentations are supposedly perfected, standardized, and groomed for consumption. In place of that promise, speech collapses into stutters and half-thoughts, the microphone an extension of the nervous system rather than a transmitter of clarity. Stephanie Cumming’s voice warps in pitch as she declares, “You could never, ever imagine how it is to be me,” a sentence that shudders under its own burden. The store’s PA system broadcasts a man’s disembodied fantasies about personal space and access while the performers’ movements defy normative choreography.

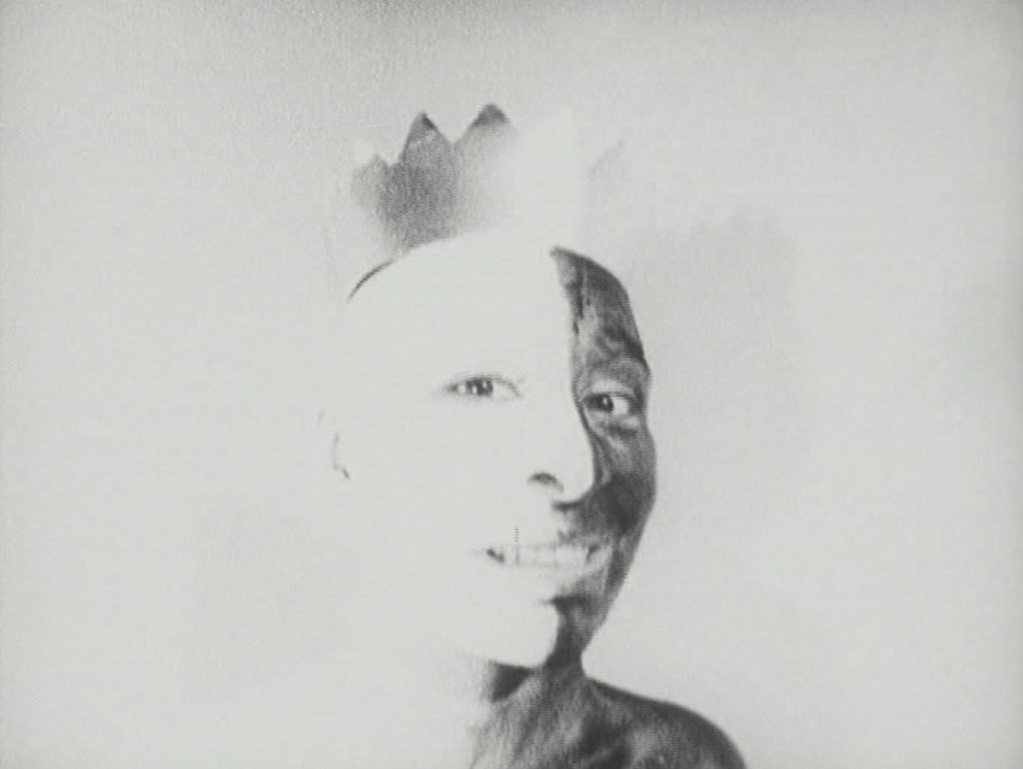

A woman undresses in a gold-leafed room, but the action refuses voyeuristic logic. Jagged and interrupted, she radiates both resistance and vulnerability. Another flexes in a mirror, adopting a male voice to brag about Cameron Diaz, rubbing the microphone against her clothing to amplify the friction of fabric against skin. So begins a chameleon’s game, with each performer trying on and discarding selves like yesterday’s discount rack. Even interaction becomes a form of dissociation. A man calls a woman on the phone but can speak only through technological mediation, misgendering her in the process, until he catches himself mid-sentence and briefly confronts his own absurdity. “Real stars shine only at night,” someone says, as if to reassure these drifting figures that obscurity is its own form of luminosity.

The emotional pivot arrives when Ulrika guides Stephanie and Johnny toward mutual recognition. She commands them to look into each other’s eyes and to listen to each other’s bodies. For one moment, care feels possible before its coherence dissolves. Voices break again, and images fracture in reflective surfaces. Giovanni emerges from his elevator only to be met with Ulrika’s shriek. Stephanie impersonates Johnny over the radio while he mouths her words perfectly, a duet of dislocation performed against a backdrop of store windows meant for display but now showcasing only fragmentation.

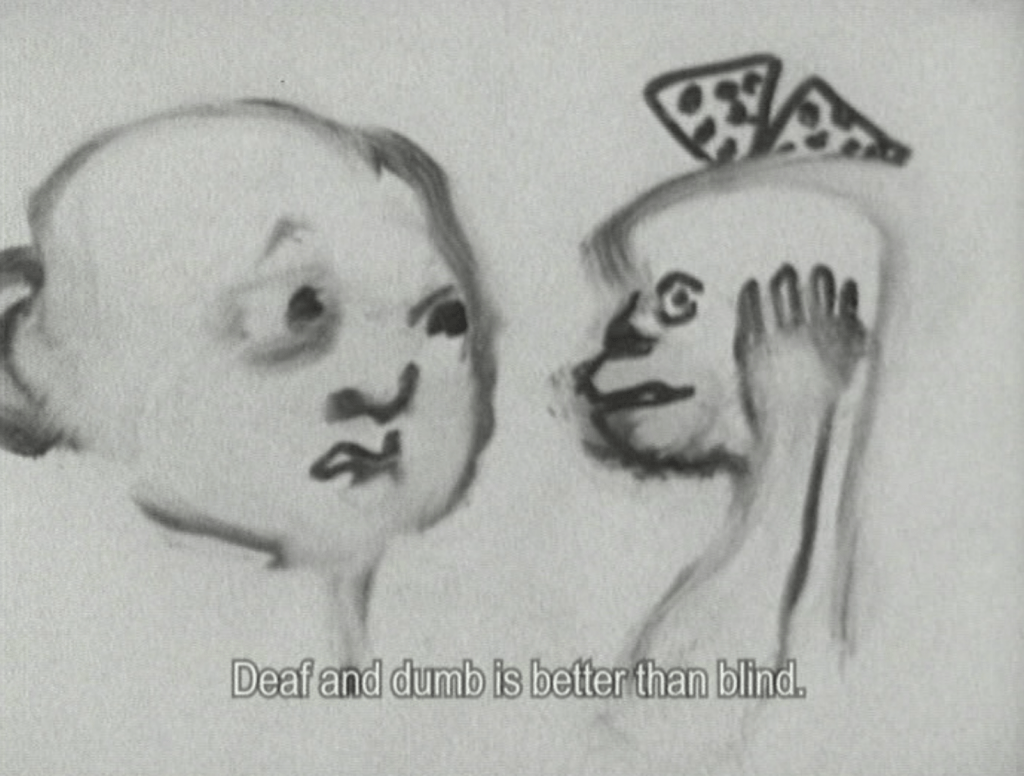

Running Sushi (2008) flings its protagonists into a pop-inflected, manga-tinged Eden that reimagines domestic life as a conveyor belt of images and half-digested memories. Stephanie Cumming and Johnny Schoofs inhabit a cartoonish household powered by manic whimsy. Eve eats an orange peel whole, every scrape and chew amplified with grotesque clarity. Adam recoils from behaviors he cannot explain and hyperventilates himself into animality. Their conversations veer from banal domestic choices, such as what color to paint the kitchen, to sudden eruptions about sexual assault and the enslavement of domestic expectations. Yet the film refuses tragedy. It vacillates between slapstick and trauma, between whispered tenderness and squeals at their own nakedness. The appearance of Eve’s chopstick-wielding alter ego, puncturing the veneer of calm, is an eruption from a psyche with a backstage pass. The two end on the floor, singing to a ukulele, a moment of fragile equilibrium in a world where even sincerity feels like performance.

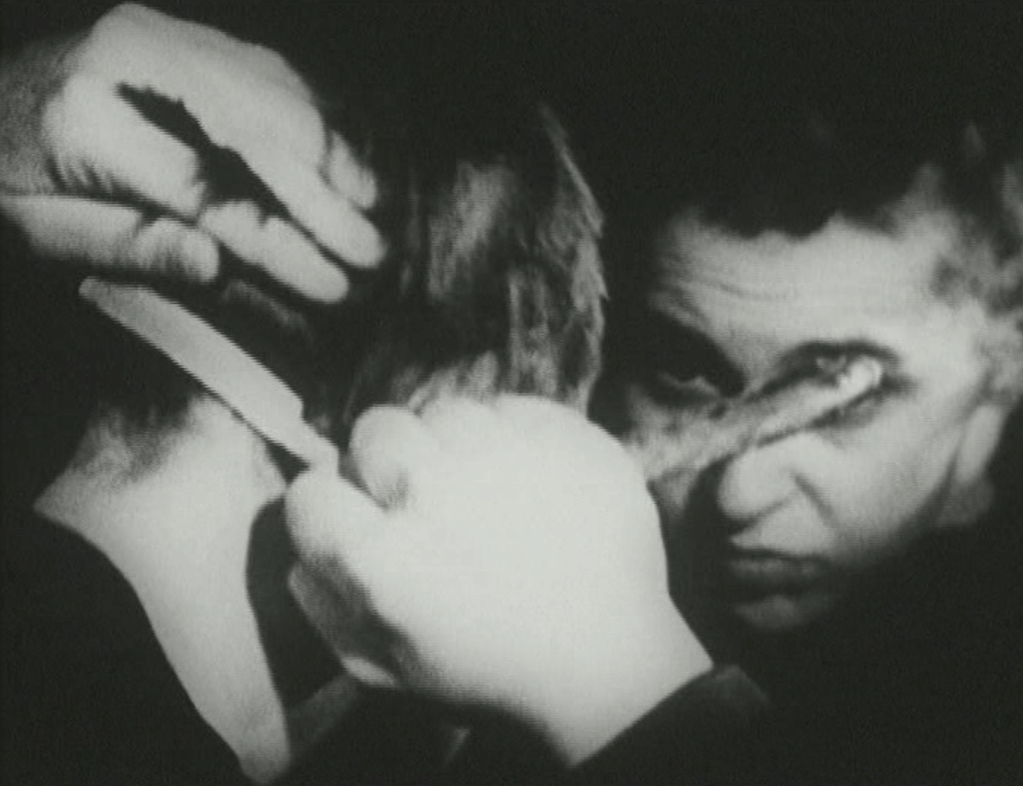

Burning Palace (2009), the darkest and most erotically charged of the trilogy, moves into the lush corridors of Vienna’s Hotel Altstadt. Red curtains invite comparisons to David Lynch, even though the film’s deeper kinship lies with Philippe Grandrieux. Bodies press against surfaces until they warp, voices distort into pleas, moans, and chants. Stephanie’s slowed-down narration lingers on the intricacies of a woman’s pleasure while naked men skitter through hotel rooms and hide behind magazines. Screams in the hallway are trapped between floors of desire and despair. Mock-operatic performances unravel as voices warp until the boundaries between song and wail thaw. Scenes of women feeling their own pleasure, either alone or together, alternate with men muttering non sequiturs and avoiding narrative continuity or emotional labor. A pop song melts into slowed oblivion, liquefying in response to the bodies onscreen. Laughter, ambiguous and uncanny, leaves us unable to tell whether release or derangement has been offered.

The accompanying documentary, Burning Down the Palace: The Making of Burning Palace (2011), shows how such controlled chaos arises from trust, improvisation, and risk. It confirms what the trilogy already demonstrates: the body, pushed to its limits, can overturn every lie we tell ourselves about the shape of things when its aura is sucked in through the mouth and expelled in a single twitch of authenticity.