Ghosting: On Disappearance is a treatise of nonbeing—or, perhaps more precisely, of unbeing. It is not merely about disappearance but about the existential tremors that ripple outward when presence collapses into absence. Placing his authorial thumb and forefinger on the touchscreen of this modern inevitability, Dominic Pettman enlarges its finer gradations across emotional, social, and technological contexts. He pinches and stretches the phenomenon until its translucent membrane reveals something more fundamental: that to vanish is to be human and that to experience the vanishing of another is to feel the sting of impermanence.

While the titular concept has haunted language for centuries through folklore, spirit mediums, and psychological estrangement, it has, in our present age, acquired a peculiarly digital valence. Now, “ghosting” refers most commonly to the quiet, sudden severance of connection between friends, lovers, or kin. The gesture is at once devastatingly simple and infinitely complex: a single tap on a block button, a name fading from a chat log, a conversation frozen by the unrequited ellipses on the book’s cover. Technology makes the act almost frictionless. We already interact daily with people who are physically absent, replaced instead by avatars, text bubbles, and disembodied voices. To ghost someone is merely to withdraw the illusion that they were ever really there to begin with.

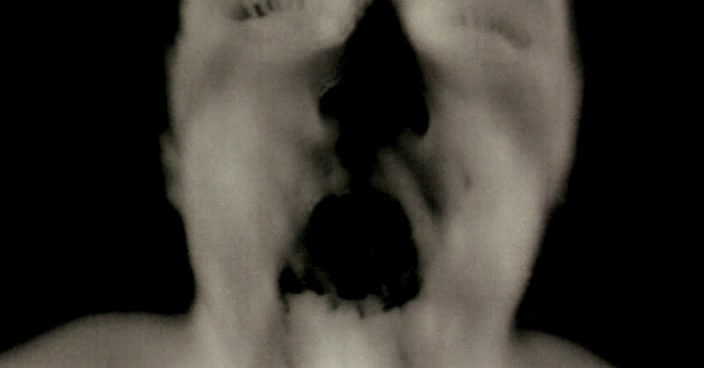

Pettman calls ghosting “a form of symbolic suicide,” if not also of violence, a dual wound inflicted upon self and other. It kills the relationship from both sides, leaving the ghosted “gasping at the silent vehemence of the act.” In centuries past, a ghost was thought to be an uncomfortable presence: the whisper in the night, the chill in a boudoir. Today’s specters, however, are defined by the unread message, the unanswered call, the untraceable unfriend. The modern ghost mocks us not with its return but with its refusal to reappear. What once demanded ritual now requires only signal and silence.

Ghosting has become, Pettman suggests, a modern luxury of the unencumbered self, one that allows us to discard what feels burdensome with the efficiency of deleting a file. Yet, what artifacts remain in the wake of such apparently clean erasures? The book’s modest yet densely packed 110 pages attempt to reckon with these residues, drawing out the historical and technical filaments that bind our vanishing acts to canonical anxieties.

Pettman walks us associatively through a gallery of geist-types, beginning with romantic ghosting. Once upon a time, the rules of engagement in love were dictated by proximity and propriety; now, they are replaced by rules of disengagement. The refusal to reply, the closing of a digital door, has become the reigning leitmotif of romantic punctuation. Where a lover might once have ignored a letter and let absence ferment over time into torment, today’s nonresponse hits instantaneous and permanent. Yet, as Pettman notes, the old dynamic persists despite our devices.

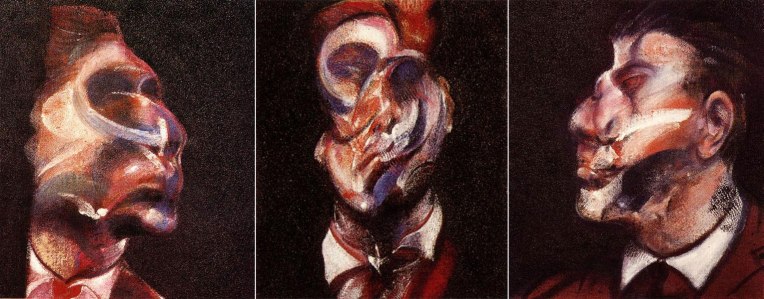

Romance has always been a theatre of projection, a negotiation between the seen and the unseen, the flesh and its fantasy. For all our bodies’ sweat and trembling, it is the embellishment that endures. Even in love’s most carnal moment, that fleeting dissolution of self into the other, there is already the seed of absence: the tiny death, the out-of-body vanishing we call climax. How curious, then, that the purest expression of intimacy is also an act of ghosting, the self evaporating in the ecstasy of its own undoing.

Ghosting also bears the battle scars of gendered terrain. Though often cast as an act of cruelty, Pettman reminds us that ghosting can just as easily be a form of survival, a necessary defense against the predations of aggression, stalking, or abuse. It can be liberation or surrender, sanctuary or exile. Either possibility, he writes, makes us acutely aware of our dependence on the other, the fragile scaffolding of recognition upon which our identities are built. In an age when partners must fulfill multiple roles once distributed across an entire community, the dissolution of a relationship casts us into a kind of social purgatory, suspended between connection and isolation.

Pettman insists, too, that ghosting is not an anomaly but a revelation of what we have always been: phantoms speaking to one another through the veil of mortality. Every “forever” whispered in the heat of the proverbial moment carries the irony of death; every “I love you” is also an elegy. Love itself unfolds under the shadow of the crypt. Perhaps this is why its rituals resemble religion, as both court devotion and doubt in equal measure, laying faith on the altar of inevitable loss.

I would add, by way of illustration, Robert Zemeckis’s Cast Away, a love story indelibly marked by absence. Chuck Noland (Tom Hanks), presumed dead after a plane crash, clings to a pocket watch containing his lover’s photograph, a relic of connection that fuels his will to live. When he returns after surviving for four years alone on a deserted island, he finds life has moved on without him; his beloved has remarried, rendering him the rarest kind of ghost, one who walks among the living, uninvited. His resurrection is itself a disappearance, a return that negates the meaning of home.

When lovers become projection screens for our own incomplete scripts, separation becomes not only likely but inevitable. The one left behind suffers not merely the withdrawal of a person but of the narrative that sustained them. In our culture of curated selves, ghosting has even acquired a perverse glamour as a badge of autonomy. One might recall Elaine Benes’s “spongeworthy” calculus from Seinfeld: who is worth the risk, the effort, the finite resource of bodily attention? Ghosting may be seen as a reversal of this privilege, a self-anointed freedom to choose extracourse over intercourse.

How, then, does one navigate the 50 shades of this phenomenon in an ecosystem already saturated with specters? As Pettman observes, “The paradox of the streaming age applies also to love: there are a million shows waiting to be watched, and yet none of them seem worth committing to.” In such a world, ghosting is less an exception than a rite of passage, a sacrament of connection where fulfillment is as fleeting as a notification bubble.

From romance, Pettman moves to the familial and the platonic. Here, the stakes deepen. To be ghosted by a coworker is unfortunate; to be ghosted by a child is practically biblical. In the age of ideological polarization, even the Thanksgiving table becomes a séance for the missing. The empty chair may symbolize courage to one and betrayal to another. Ghosting thus becomes political, echoing across generations and belief systems.

Professional and social ghosting occupy the book’s latter thrust, and here Pettman’s insights cut to the bone. Having once taught as a professor, I recognize the spectral economy of intellectual labor, the endless treadmill of unacknowledged effort and unreciprocated outreach. In graduate school, “imposter syndrome” was our ironic communion, a collective haunting where each scholar feared being the least real presence in the room. Every unanswered email, every “no reply” rejection, each job committee that never called back—all were tiny funerals for the self. Eventually, I chose to ghost the profession before it could continue to ghost me, if only to preserve a flicker of something to call my own.

Of course, ghosting is by no means confined to ivory towers. It infiltrates every professional exchange: clients disappearing mid-project, employers denying promotion for no apparent reason, friendships fading in inbox drafts. Even places ghost us: favorite restaurants that shutter without warning, neighborhoods transformed overnight, ecosystems collapsing out of sight. The world itself feels like it is ghosting us, withdrawing one news cycle at a time into abstraction. The more we exist, the more unreal reality seems.

I would add two more iterations to Pettman’s catalogue. First is the phenomenological ghosting of presence without feeling. We find this in M. Night Shyamalan’s After Earth, in which ghosting refers to the process of shutting down one’s emotions. This quality is a precious commodity in the film’s military-industrial complex, weaponized to render one invisible to alien predators who target their prey by detecting fear pheromones. To ghost, here, is to master disappearance from within. Second is Deanimated, an experimental film by avant-gardist Martin Arnold, who digitally erases actors one by one from the 1941 Bela Lugosi picture Invisible Ghost, until all that remains are empty rooms, doors that open by themselves, and dramatic music without diegesis. The world goes on performing, emptied of its inhabitants. The viewer, too, becomes ghosted, watching absence itself take center stage.

The loss of the one who ghosts us, Pettman ultimately suggests, is not merely a social wound but an ontological one. We lose not only another person but the mirror in which our own being once took shape. The terror of ghosting lies not in being forgotten but in discovering how easily we can forget ourselves when deprived of the other’s gaze. Technology did not create this fragility but has only revealed that relationships have always been provisional, sustained by faith, fantasy, and the flickering persistence of attention.

To be ghosted, then, is to confront the truth that love, friendship, and community are nothing more than brief illuminations against the endless dark of unbeing.