It would be easy to say that guitarist, composer, and producer Charlie Rauh charts a territory all his own. But to fall into that cliché would risk eliding the tender graces that have fueled his endeavors from the beginning. He averts his eyes from the road less traveled, setting his heart instead on that still bearing the footprints of ancestors related either by blood or artistic heritage. Whether tuning his guitar like a microscope to the poetry of Phillis Wheatley or Anne and Emily Brontë or flipping it around like a telescope in the warmth of such albums as Viriditas and Hiraeth, he never lets go of the human condition as a central concern.

This debut musical treatise bears the subtitle “An Approach to Creating Intentional Music.” And yet, what is so refreshing about the narrative offered in these pages is that you need not be a musician, intentional or otherwise, to benefit from its insights. Central among them is that we tend to back down from the passion projects we hold dear in our youth. As time tempers these into rote platitudes (“hobbies at best, hidden out of embarrassment at worst,” he notes in the Foreword), we treat their recession as inevitable. This is, perhaps, one reason why literary works and all the paratextual experiences they entail have been integral to his oeuvre for so long. In that sense, he is as much a translator as a composer.

In the first section, “Simply,” he reflects on his time studying improvisation with jazz pianist Connie Crothers. Instead of bowing to the (relatively recent) convention that tells us simplicity is a bad thing, he embraces it as “a pure distillation of identifiable quality” that allows complexity to breathe. I cannot help but liken it to a line drawing of a wing versus a massive Baroque painting filled with saints and cherubim. The burden of proof on the creator of the former is deeper in the sense that every line speaks nakedly on the page, whereas in the latter, the margin for self-indulgence is greater yet more easily concealed. What Rauh realized at a key turning point in his growth as a musician was that complicating matters with business wasn’t the end goal. It was tapping into the childlike curiosity that such veneers, fragile as they are, do a surprisingly good job of hiding. This does not mean that one must “devolve” but that one must be willing to be vulnerable. And when we are vulnerable, we confront the question of who we are in spite of ourselves.

“Patiently” brings us into the spiritual weeds, through which every glimpse of sunshine becomes a tether to hope. More than that, it is the ultimate expression of love (think, for example, of the long-suffering God who stays his hand so that we might learn from our mistakes). And so, patience is not about proving your limits of tolerance but about faith as the evidence of things unseen. As Rauh humbly admits, “This is easier said than done, and despite my best wishes, I cannot claim that I am fully in tune with the concept as it applies to my life.” Amen, and amen.

Patience, too, is a mode of healing. It is the promise of strength fulfilled and renewed through the perseverance of the human (and animal) spirit. By tempering our fears, it gives room to stretch out our egos and cut them into millions of pieces. On the practical side, patience makes it “not only acceptable but optimal to leave spaces in your workflow.” Without those spaces, we lose sight of ourselves and what we are capable of. The moment we say we have arrived is probably when we need to check our assurance at the door and start singing again for its own sake.

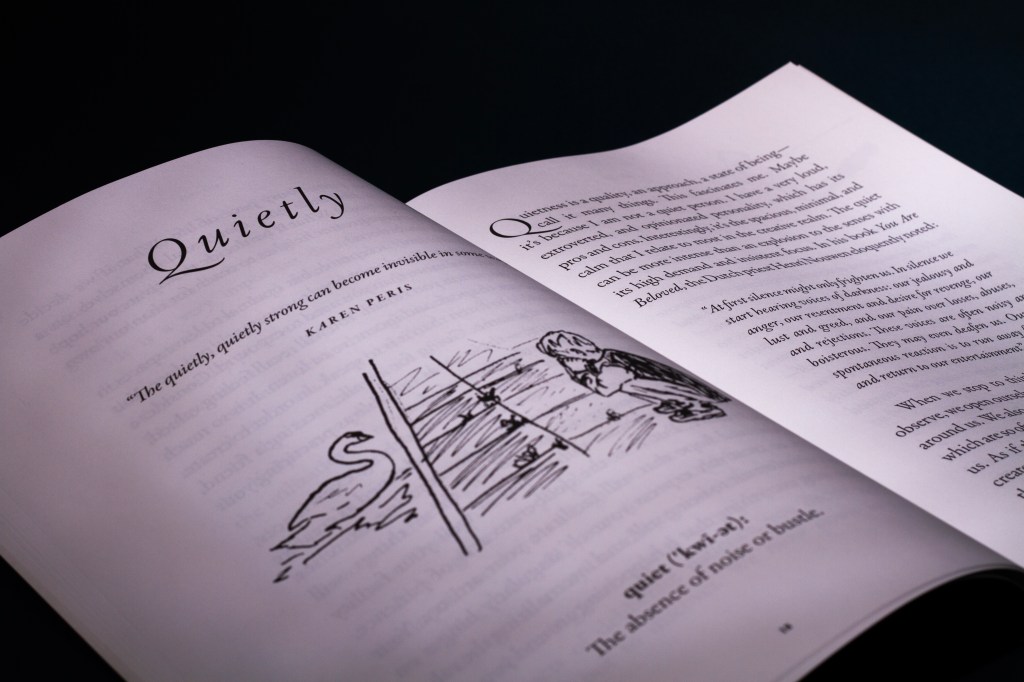

The book’s third act, “Quietly,” is where the soul comes most readily into play. That said, quietude isn’t some mystical state of being in which one achieves unity with the universe but rather a recognition that the melodies of our lives need volition to seek one another out. And that is where the youthful essence from which we have distanced ourselves must be fished from within. Children are nothing if not intentional, and such clarity of expression is where we get our profoundest ideas. To be silent is to see ourselves no longer through the filters of camera lenses and computer screens but rather in the naked truth of the proverbial mirror. In so doing, we realize just how noisy we are inside.

I am reminded of an anecdote involving John Cage, who stepped into an anechoic chamber with the intention of experiencing true silence, only to discover that the faint sounds of his circulating blood and nervous system rendered that concept moot. This experience happened to be the inspiration behind his infamous composition 4’33”, for which the performer sits quietly in front of a piano for the titular duration without playing a single note. In hindsight, what was so disturbing about the piece’s premiere wasn’t necessarily that Cage was poking fun at the academy or even philosophically questioning the very definition of music; it was the fact that the performer ceased to matter. Thus, to experience 4’33” live is to be flooded with all sorts of internal voices. In wrestling with this same tension, Rauh concludes that the result of quiet music isn’t boredom or relaxation but power. It also tests our mettle as listeners and clues us in on the creed of patience. “When the rest falls away,” he observes, “all that is left is all we can give.”

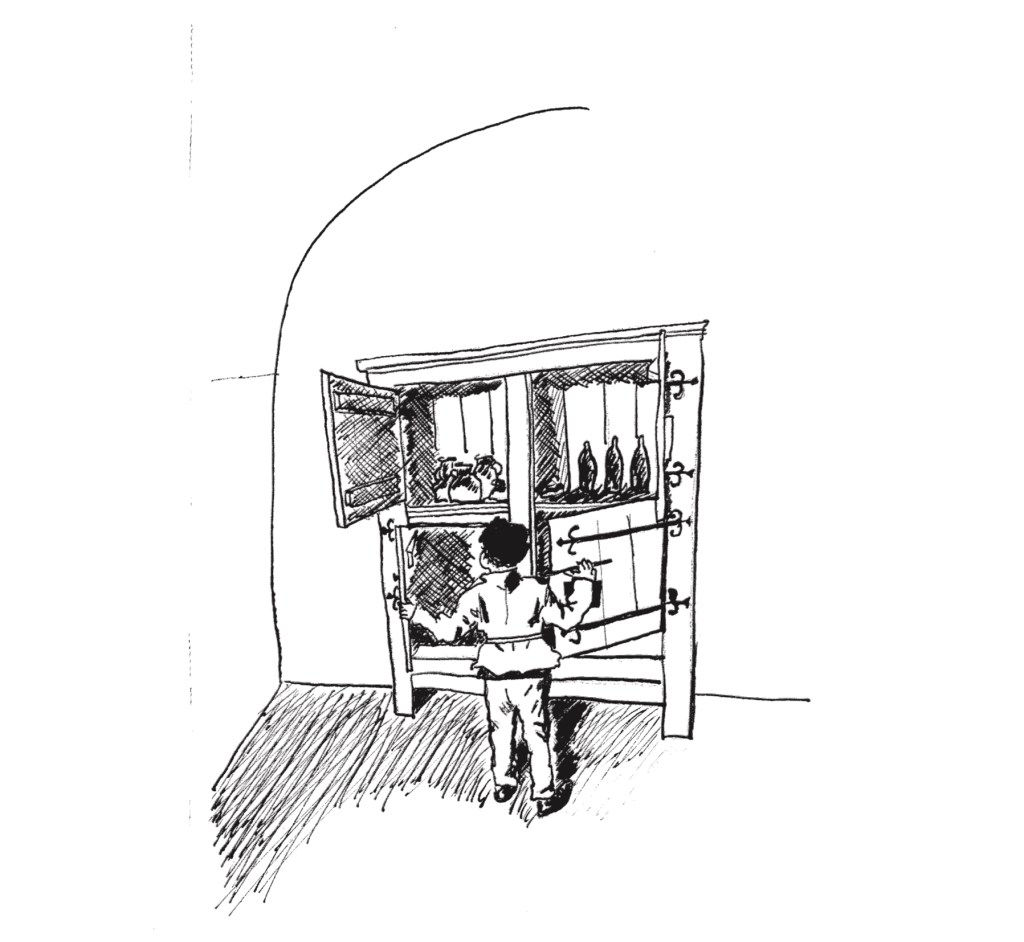

No review of this superbly rendered meta-statement would be complete without mentioning the contributions of his sister, Christina Rauh Fishburne, whose illustrations are the glue that binds. By turns whimsical and contemplative, they work in counterpoint to the text without ever intruding. One in particular, which appears on page 24, speaks to the nostalgia of this reader/viewer. Its depiction of curiosity, stripped of all the baggage that adults bring to this impulse, teeters on the edge of interpretation. It is also the first of a sequence of images that home in on key aspects of the words preceding them.

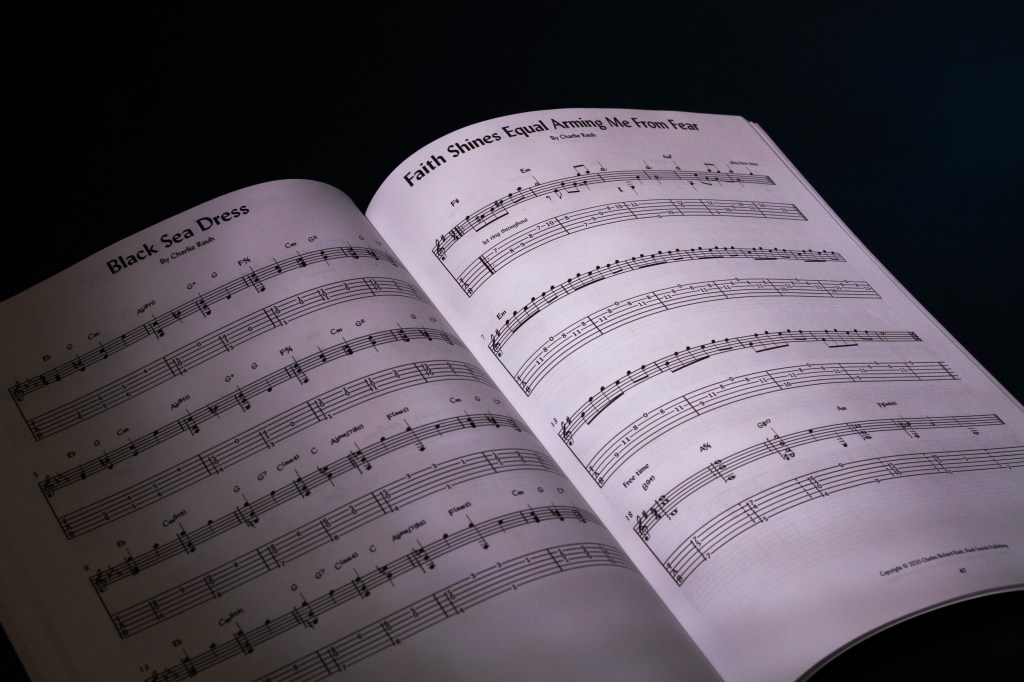

Whether in the domestic comforts of a life without clear and present dangers or in the wider view of time and its inevitable entropy, Fishburne’s ability to pull out memories we never knew we had is a blessing and a comfort. As a segue into the scores included herein, they are denizens of a time capsule that is itself the curio of another time capsule. Of said scores, the musically inclined among us get access to a swath of moods. From lullabies to choral settings, they offer plenty of soil in which to plant and water seeds of communion, assuring us that we can rest our heads on pillows of wonder every night, knowing there is only more to come when day breaks.