Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s Notes on Film approaches moving images as a palimpsest, a surface carrying its past as half-erased inscriptions waiting to be pressed into new shapes. His practice is less a restoration than an exposure of fault lines. By reorganizing and reprocessing inherited material, he forces it into states where certainty dissolves, each fragment a visual equation caught and interrupted in the act of solving itself. The archive becomes a reservoir of dormant energies, coaxed out with a mixture of severity and play, always attentive to how a single gesture or sonic abrasion can convert the familiar into a cognitive riddle. Under his hand, the storytelling apparatus mutates into a thinking machine.

notes on film 01 else (2002), the first entry in the cycle, recalibrates a scene from Paul Czinner’s Fräulein Else (1929) as a drifting hypothesis sustained by new additions. The woman in question, repeatedly summoned into a perpetual screen test, becomes less a character than a set of possible identities seeking traction on surfaces that cannot stabilize her. The word IF migrates along the frame’s lower edge, assembling and dispersing itself with a logic too unstable to resolve, yet too insistent to ignore. Wolfgang Frisch’s score stretches the material into a hypnotic trance where syntax becomes sensation. Lines rising and falling resemble a nervous system diagram or the first hesitant scratches of a manifesto that refuses to speak through fleshly instruments. One feels caught inside a conditional mood: If this happens, what follows? If she exists, then who am I? The result is a thought experiment that dramatizes the contingency of meaning itself.

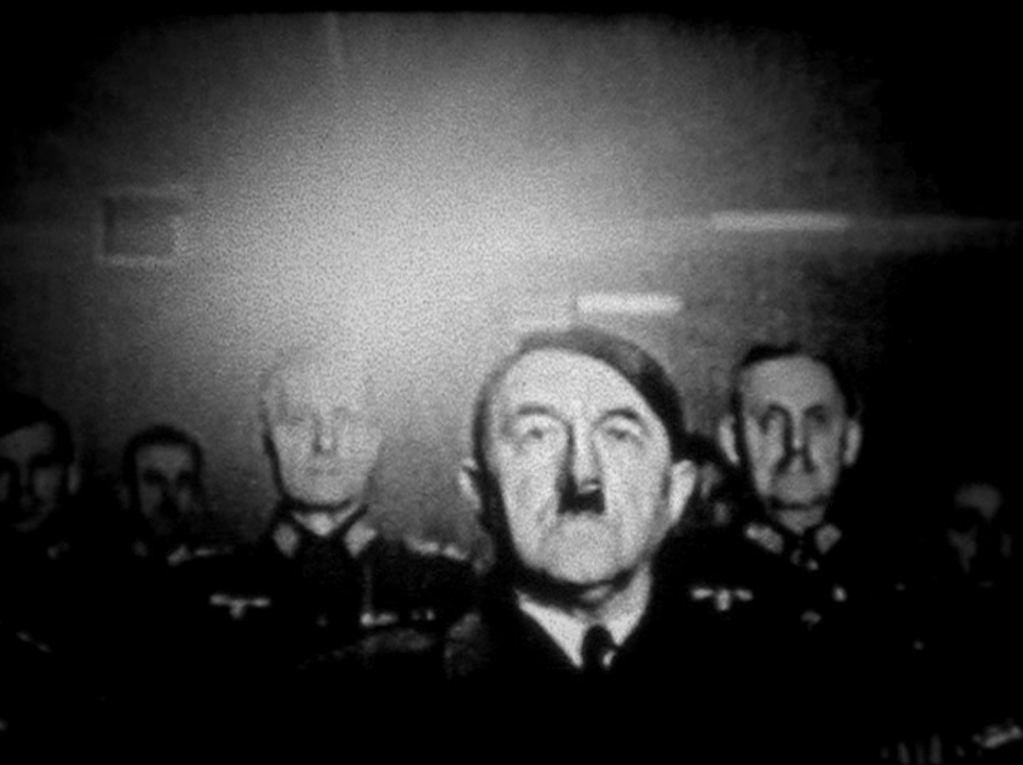

The most chilling configuration appears in Conference (Notes on Film 05) (2011), which assembles 65 portrayals of Adolf Hitler. Pfaffenbichler arranges them as if they were a group of singers rehearsing a single monstrous chorale, each voice tuned to a different frequency of delusion, rage, or parody. The moustache becomes a floating glyph emptied of significance through repetition, a marker of historical exhaustion and cultural overexposure. Udo Kier’s fevered performance in Schlingensief’s 100 Jahre Adolf Hitler shares oxygen with Mel Brooks’s mockery and Chaplin’s trembling poise. Pfaffenbichler maps their common repertoire: the violent doorway entrance, the serpentine regard of subordinates, the thunder from the balcony. Sound forms a coarse landscape of distorted peaks. At one point, “Hitler” sits in a theater watching himself, an abyss that curls back into paranoia until the image-world appears implicated in the very fantasies it attempts to critique. What remains is static, as though representation itself had been scorched.

INTERMEZZO (Notes on Film 04) (2012) lights the fuse of early slapstick and detonates it from within. Pfaffenbichler extracts Chaplin’s escalator tumble from The Floorwalker (1916) and reshapes it into a high-voltage rock montage. Frisch’s guitar tears through the field while the fall is mirrored and refracted into a cascading collapse of gravitational logic. The stumble becomes an endlessly recomposed event in spacetime, a pattern slipping into abstraction, recombining itself, and falling again. The gag dissolves into pure kinesis.

A Messenger from the Shadows (Notes on Film 06A / Monologue 01) (2012) expands this logic into a full-scale resurrection of Lon Chaney. Drawing from all 46 extant features, Pfaffenbichler constructs a temporal chimera in which The Man of a Thousand Faces confronts his own proliferating identities. The result moves with the feverish drift of a nightmare: Chaney gazing at a building’s façade as shadows creep across it; hands emerging from nowhere to deliver warnings; characters dialing telephones that connect to alternate versions of the same man. Orientalist disguises, phantom wounds, and grotesque prosthetics recur as though lost inside a self-made labyrinth. Rain and smoke invade the frame until the building burns, the figures collapse, and only a lone spotlight remains, illuminating emptiness where onlookers should be.

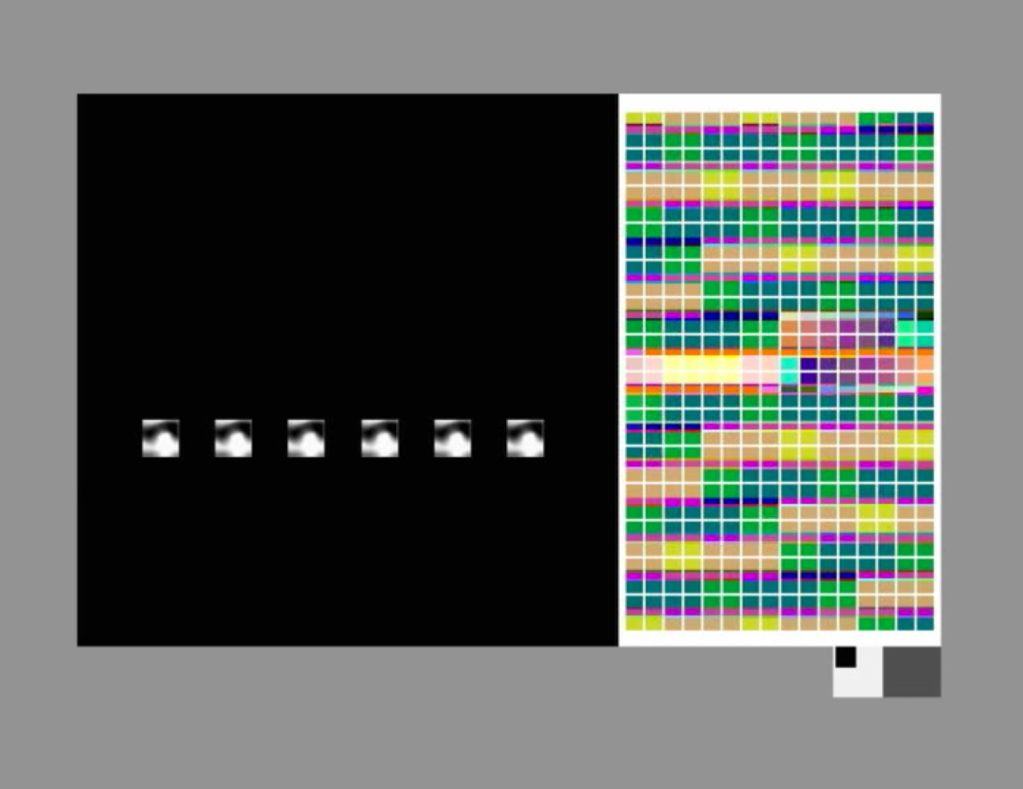

The bonus piece, 36 (2001), made with Lotte Schreiber, pares moving images down to patterns and sequences derived from the titular number. Its structural rigor anticipates the methods that follow: repetition as revelation, mathematics as atmosphere, the image as a system generating its own permutations.

Across the cycle, Pfaffenbichler demonstrates that the moving image is never simply hereditary. In being reactivated, it takes on shades of the era in which it now awakens from its coma. His pieces interrogate the archive until it confesses what it never intended to reveal. In the end, what forms is less a conclusion than a faint pressure in thought, a configuration that hovers without settling into shape. No image quite arrives; no pattern fully claims itself. Instead, an unnamed interval opens where perception senses its own scaffolding and begins to loosen it. Within this interval, meaning is neither lost nor found but suspended, waiting for a consciousness willing to meet it without expectation, to inhabit a space where recognition has not yet begun.