Peter Weibel’s Körperaktionen (Bodyworks) reveal him as the Actionist who refused the Actionists’ mythology. While others pushed inward toward abjection and self-wounding, Weibel turned outward toward media, politics, semiotics, and the body as a site where power writes its own grammar. His gestures are never self-contained eruptions. They are conceptual irritants that question whether an “action” is an event, an inscription, a perceptual trap, or an estrangement from social order. The body becomes the primary medium not because it grants access to primal truth but because it is the site where systems fray at the seams.

This appetite for estrangement is already present in Fingerprint (1968), which uses the film strip to produce sound, image, and a forensic poetics of identity. A print is an index of presence, a bureaucratic marker, a residue of control, and, finally, a reminder that the flesh leaves traces, whether we like it or not. Nüstern (Nostrils) and Lüstern (Lascivious) (both from 1969) push the close-up toward distortion until isolated members appear as media property rather than human attributes. A magnified nose, an eroticized massage revealed as nothing more than an orange, both dismantle the consumer industry’s habit of slicing us into marketable zones of sensation.

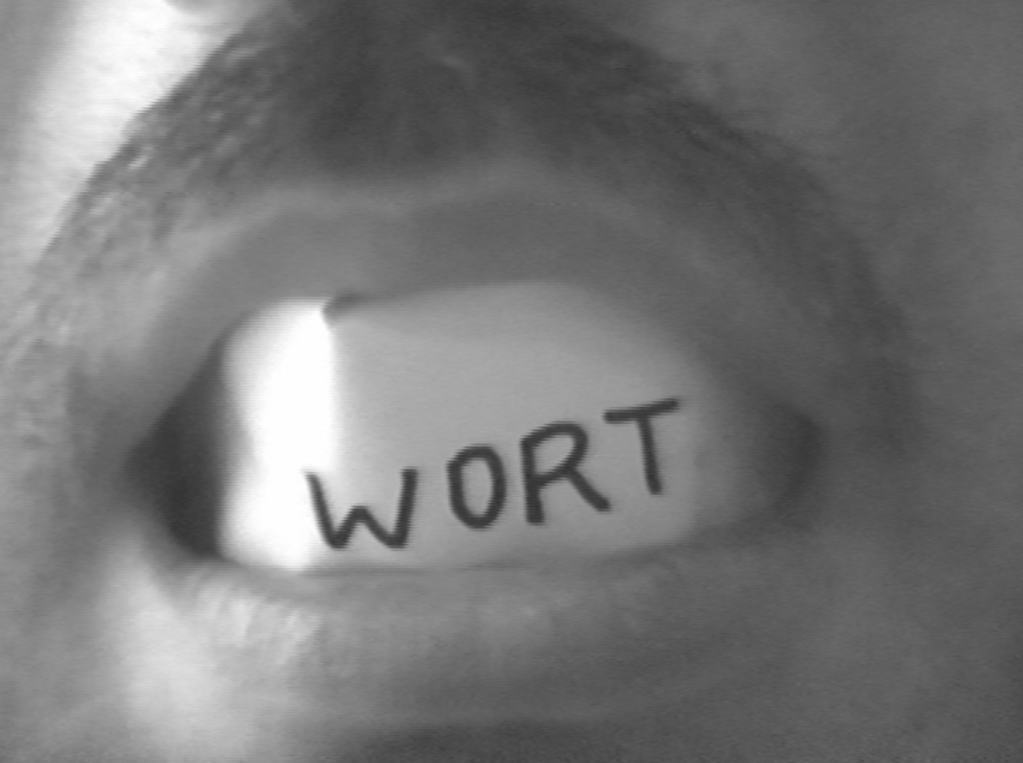

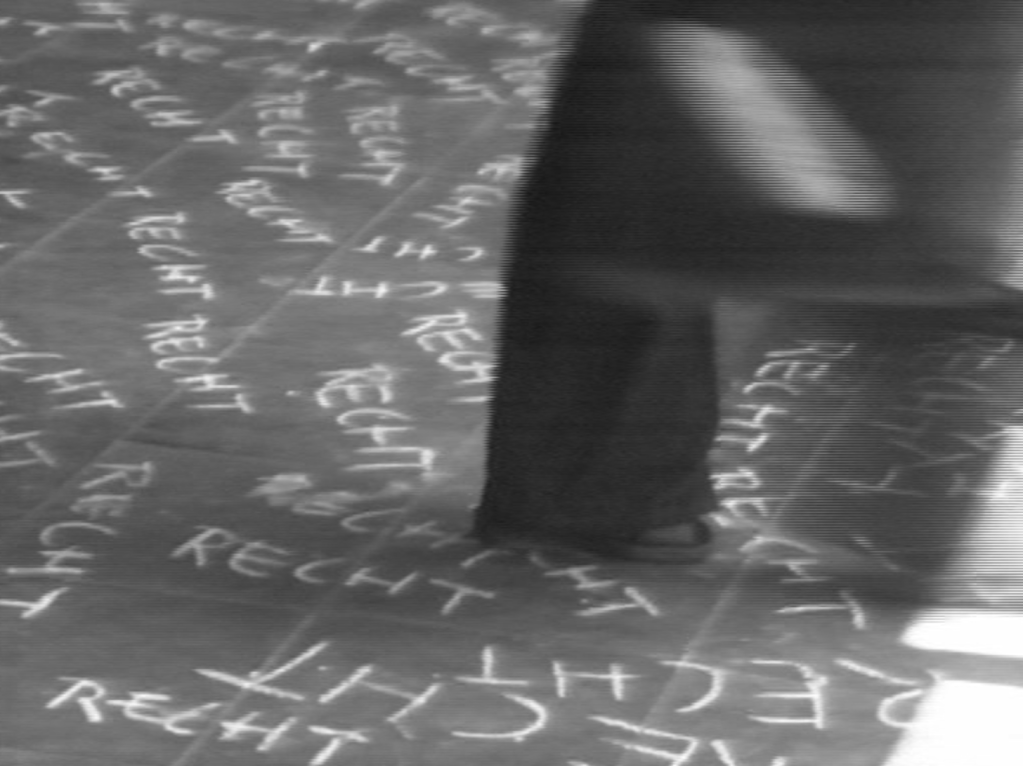

The Text films from 1974—Augentexte, Mundtext, Stirntext—literalize the notion that the body speaks. Yet the speech is stuttering, mechanical, self-consuming. The eye blinks words, the mouth utters “SCHEISSE” before swallowing it, the forehead writes until it throbs. Language contaminates skin and vice versa. In Das Recht mit Füßen treten (Trampling on Rights, 1967/68), museum visitors step on the word “recht” scattered across the floor in an unwitting political gait. Here, the act belongs to the public, hinting at what is perhaps Weibel’s most radical proposition: spectators are never neutral. Lösung der Phantasie (Solution of Fantasy, 1972) examines hair as a philosophical emblem, elegant when attached to the head and repulsive when shed, offering a small but potent meditation on beauty and decay sharing the same root.

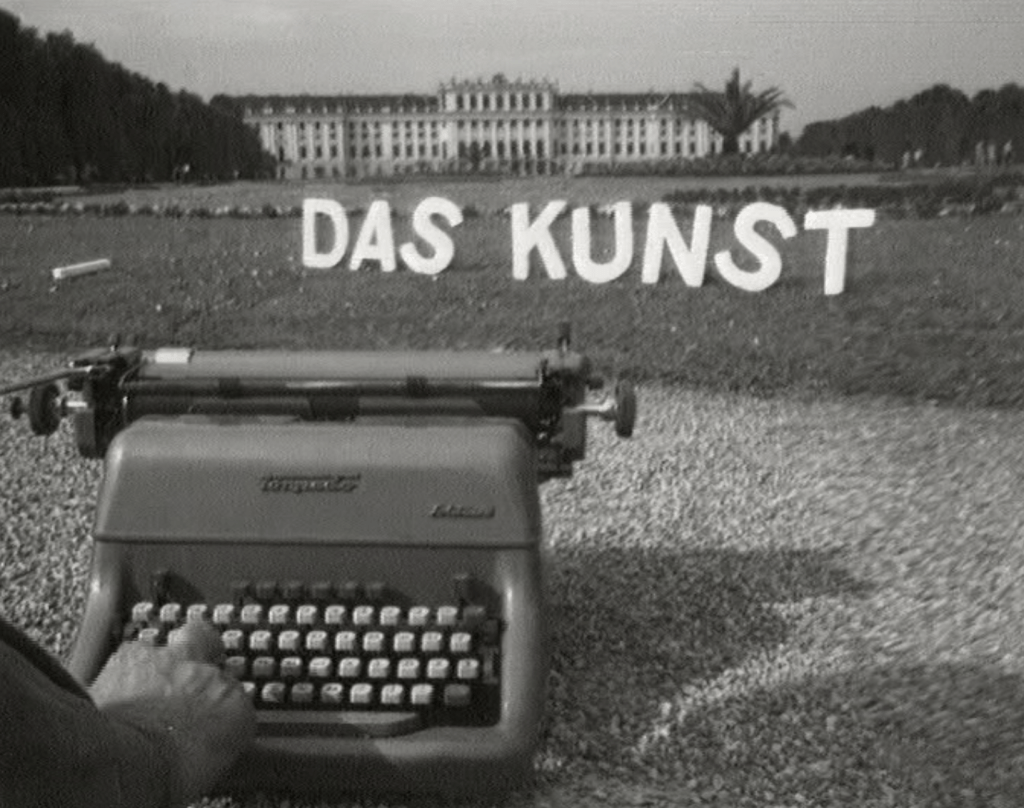

Weibel often condenses his motifs of interest into crystalline forms. Wie hat sich aus den Fischen die Mathematik entwickelt? (How Did Mathematics Evolve From the Fish?, 1971) is a self-styled visual haiku centered on a typewritten iteration of “hand,” zooming until the word mutates into a pure visual pattern. Fluidum und Eigentum: Körperverhältnisse als Eigentumsmaße (Fluidum and Property: Body Relations as Measure of Property, 1971/72) examines the idea of property by asking at what scale ownership collapses: bread, chair, room, shadow. Each item passes through the body’s orbit of affordance and discards the illusion that possession is stable.

Such explorations of symbolic order continue in Grüß Gott (1967/72), where Weibel and Susanne Widl casually eat pretzel letters forming the titular greeting, turning Austrian piety into edible farce. Kokain(e) (1972) reveals a pornographic image hidden beneath a can of fish printed with St. Stephen’s Cathedral, suggesting that sacred and obscene imagery differ only by their packaging. His reconstruction of Duchamp’s Stoppages-étalon (1970/71) reenacts the dropping of a thread to show that randomness, not symmetry, is the geometry of modernity. Vulkanologie der Emotionen (Vulcanology of the Emotions, 1971/73) arranges bodily poses as geological layers of feeling, while whale-like moans push the human voice toward prelinguistic depths.

Weibel’s inquiry into the politics of looking continues in Aktbesprechung oder Inverses Selbstporträt (Discussion of the Nude or Inverse Self-Portrait, 1975/76), which reverses the male gaze by showing male nudes through women’s descriptions. The men become mirrors without agency, their vulnerability revealed through shifting reactions. Switcher Sex (1972) overlays body parts into unstable configurations, turning gender into an assemblage that resists coherence. Venus im Pelz (Venus in Furs, 2003) uses morphing technology to blend centuries of painted Venuses into a single monstrous continuum, exposing the canon as an endlessly repeated, idealized submission. Vers und Vernunft (Rhyme and Reason, 1978) stages Weibel and Widl in a cage of television screens, grunting and breathing themselves into exhaustion until reason gives way to an animal rhythm. Zeitblut – Blutglocke (Timeblood – Bloodbell, 1972/79/83) completes this arc by spilling his own blood on national television. Through this action, every Austrian home was simultaneously filled with his life essence, as if the media had become a circulatory system carrying his interiority into the public domain.

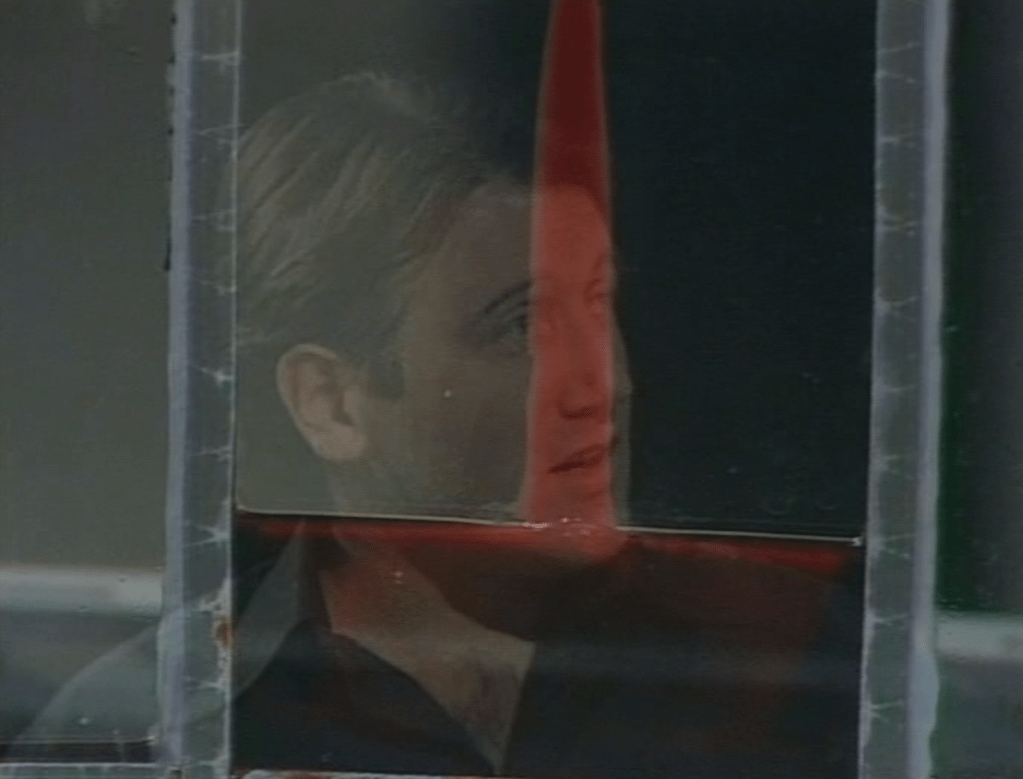

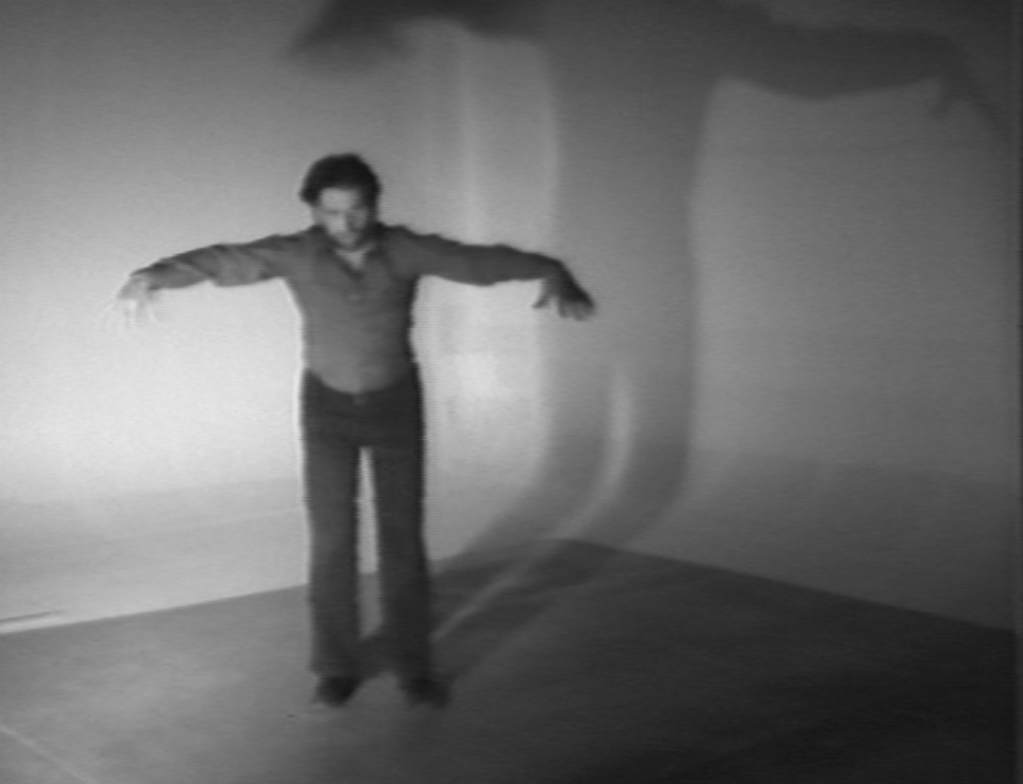

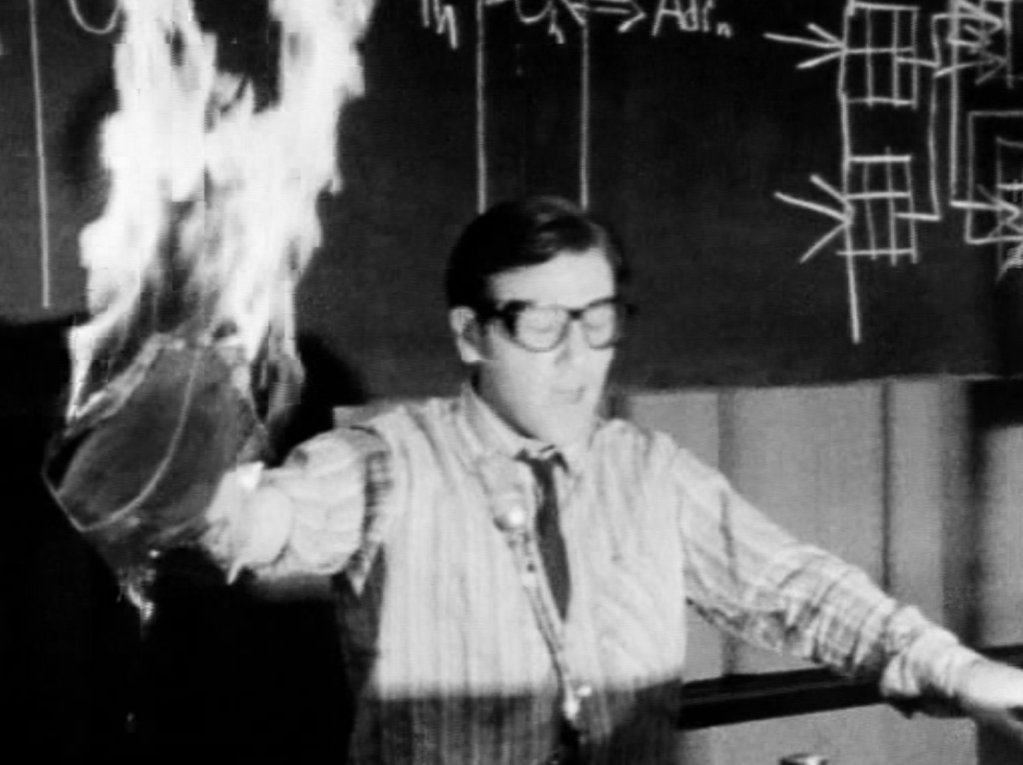

Three films by Ernst Schmidt Jr., previously seen on INDEX 042, are also included among the selections curated on this DVD. Kunst und Revolution: Brandrede (Art and Revolution: Incendiary Speech, 1968) documents Weibel’s speech from his infamous June 7, 1968, performance at the University of Vienna. With one hand aflame, he quotes Lenin and Chernyshevsky in a powerful deconstruction of rhetoric. “The goal of the speech action,” he recalls, “was to inflame consciousness, to pass the flame of revolution and freedom to its listeners, and it was realized in the form of a body action.” Denkakt (1967) captures Weibel thinking aloud until the medium truncates his thought, proving that technological limits mediate cognition itself: “[F]ilmmaking meaning nothing other than the production, derivation of figures, events according to the possibilities of the formation film, for example with celluloid or the movie auditorium, screen, spectators.” The notorious Aus der Mappe der Hundigkeit (From the Portfolio of Doggedness, 1968/69), in which VALIE EXPORT walks Weibel as one would a dog, literalizes power inversion and makes the male body the site of disciplinary display. The title is a play on Aus der Mappe der Menschlichkeit (From the Portfolio of Humanity), a leaflet once distributed weekly by the Red Cross.

Across these projects, Weibel does not use the self to enact mysticism or sacrifice. He treats it as a contested field where authority, machinery, desire, and perception collide, and where every decision reveals the infrastructures attempting to constrict it. His Actions expose that the body, even in the absence of a camera, is already mediated by the lens of the human eye and that the screen is not a recording device but a palimpsest for sociopolitical fictions. Over decades, Weibel has pursued nothing less than a decolonization of the sensorium. He invites us to notice what we have been trained to ignore, to feel what we anesthetize, and to recognize how deeply the rules of visibility are written into these bags of bones we imagine as our own.