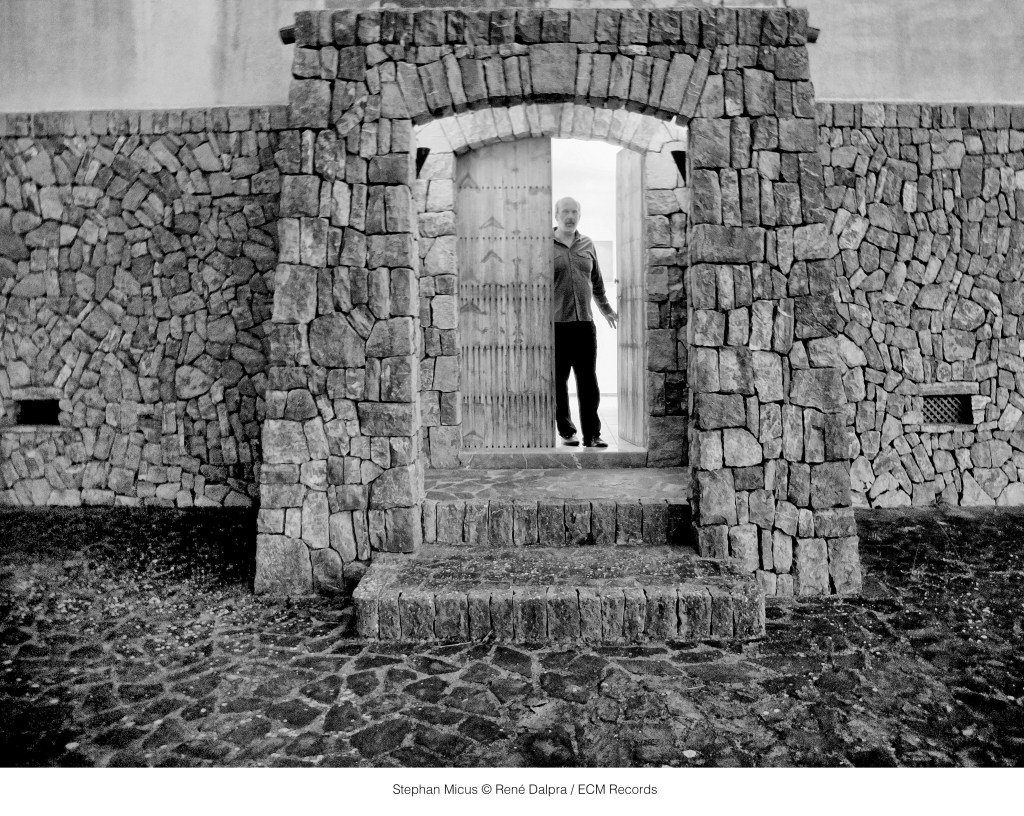

Stephan Micus

To The Rising Moon

Stephan Micus tiple, dilruba, sattar, chord zither, tableharp, nay, sapeh

All music and voices composed and performed by Stephan Micus

Recorded 2021-2023 at MCM Studios

Cover art: Eduard Micus (1925-2000)

An ECM Production

Release date: November 15, 2024

my house burned down

now I have a better view

of the rising moon

–Masahide Mizuta (1657-1723)

To step into a new Stephan Micus recording is to approach a koan from the inside out. For while every world he creates feels immediately familiar, there’s also something about it that distances us from ourselves. In To The Rising Moon, his 26th solo album for ECM, he unravels an out-of-body experience through characteristically novel combinations, transcending cultural and historical borders in search of a collective humanity.

His narratives always seem to have a central protagonist; this time, it is the tiple. Sounding like a charango but with a looser feel, it is the national instrument of Colombia, but in the present context, it steps out of space and time into its own. “To The Rising Sun” features two of them: one to establish a percussive jangle, the other to sing through its contours. Building a monument one stone at a time, even as Micus scales it, he comes prepared with the finishing capstone, so that we can fully admire the valley of which it affords a sacred view. This format is later replicated in “Unexpected Joy,” which has all the internal tension of a young warrior walking through the forest on his first solo hunt, and in “To The Lilies In The Fields,” where gemstones rounded by the river’s current are ignored in favor of the greater value of leaving them as they are. “In Your Eyes” increases the count to three and adds a lone voice. Its juxtaposition of steel strings and Micus’s rounded singing gives us room to explore. At the heart of all this is “The Silver Fan,” a tiple solo through which light and shadow merge with a kiss.

On the topic of voices, another prominent one is the dilruba, an Indian bowed instrument with sympathetic strings. Six of these band together for “Dream Within Dream,” painting a realm where the physical world recedes into the farthest corners of consciousness. The sound is thin and incisive. Like wisdom offered by a sage on his deathbed, its truth can never be forgotten. The dilruba finds a long-lost brother in “Embracing Mysteries,” where the sapeh, a four-stringed lute from Borneo (normally plucked but modified to be played with a bow), evokes nature and nurture in equal measure. Meanwhile, Micus’s voice cuts the figure of a traveler with a rucksack filled with hymns, which he drops in place of crumbs.

Yet another member of this ad hoc family is the sattar, a long-necked bowed instrument of the Uigur people. In triplicate, it elicits one of Micus’s most spiritual creations: “The Veil.” He runs his hands gently across, feeling every pleat and fold as if it were an era of history to be navigated. In that sense, there is also mourning for the past and a hope that all the destruction we’ve brought has not ultimately been in vain. Despite taking part in the album’s largest ensemble in “Waiting For The Nightingale” (which brings together two dilruba with five sattar, five voices, three Cambodian flutes, and two chord zithers), the result feels open, a spider’s web touched with dew that has withstood an entire day’s worth of climatic change. Micus’s chorusing is a call to the wilderness within. The sattar also binds three tableharps (which combine elements of bowed psaltery, zither, and harp) in “The Flame,” leaving blurred traces of its past like paintings on stone. Finally, in the title track (alongside two tiples and two nay), it is a birthing ground of fluidity and purpose. Having nowhere else to go but inward, it bows its head in offering to silence, a prayer without words to get in the way of meaning.