Volks stöhnende Knochenschau. A mass spectacle of groaning bones. The title itself is a provocation: the name of a collaborative video project emerging from the inner and outer circles of the Medienwerkstatt Wien (then known as the Verein Medienzentren). These artists understood that media is never a neutral vessel but a contested territory, governed by those who decide what may be seen, said, and remembered. In 1980, Austria had only two publicly operated television stations, ORF 1 and ORF 2. Together they acted as custodians of the public’s permissible concerns, determining not only what would be broadcast but what would be thinkable. Volks stöhnende Knochenschau arose as a revolt against this constricted horizon of visibility and its persistent fiction of objectivity.

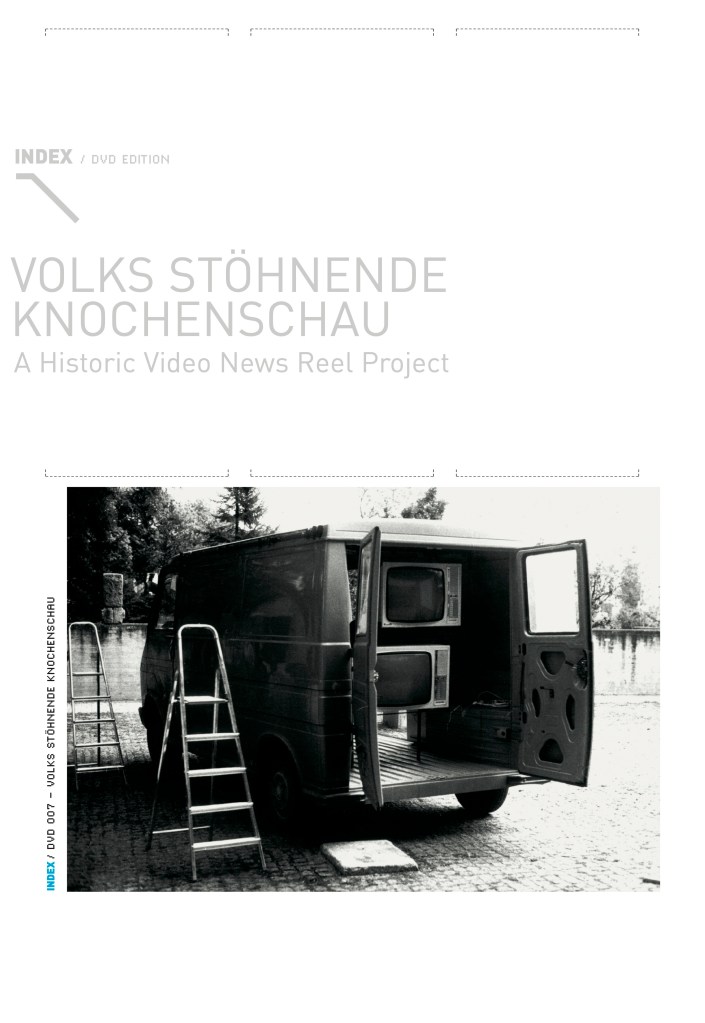

The project was conceived not simply as an alternative information outlet but as a practice of “counter-publicity.” Its practitioners sought to expand the very notion of communality by showing what official media suppressed or blurred: stories spoken from below, from the margins, and from bodies left out of state narratives. Their work was broadcast not over television airwaves but through a “video bus” that traveled the countryside during the 1980 Vienna Festival, screening grassroots “newsreels.” Such mobility was symbolic. So long as state media remained anchored in the capital—its authority buttressed by bureaucracy—these videos would have wheels, crossing borders of geography and class to reach viewers rarely permitted to see themselves.

Core contributors Gustav Deutsch, Gerda Lampalzer, Manfred Neuwirth, and Viktor Riemer cultivated a participatory ethos, inviting the public not only to watch but to speak. These works do not merely document; they listen. They reconfigure who is allowed to narrate history. This selection from 1980 offers a panorama of concerns and reveals a landscape in which truth was never static but continually negotiated.

Ungustl Atom (Unsavory Atom, 1980) is an unambiguously charged opinion piece on nuclear power, aligning itself with the November 5th Movement that sought to prevent the activation of Austria’s Zwentendorf nuclear plant on the same date the country famously voted against its operation. The video opens with dramatic, almost Górecki-like music underscoring footage of the plant, lending the structure an eerie grandeur. Street interviews follow, capturing a spectrum of attitudes. Some frame nuclear power as a necessary step toward progress, a technological inevitability. Others shrug: accidents happen everywhere. Still others invoke the Three Mile Island incident in Pennsylvania, comparing it to The China Syndrome (eerily released just 12 days prior) and questioning whether the media downplayed its consequences. One man touts nuclear energy as a strategy to reduce dependence on foreign oil, while another warns that “technical solutions very often have non-technical consequences.” A final observation laments the erasure of the human factor from media discourse, reflecting growing suspicion that knowledge has become opaque, controlled, and curated. The segment ends with a jarring image of a man dragging what appears to be a woman’s corpse and tossing her onto a heap of radioactive debris. In retrospect, it feels eerily prophetic in a world shaped by Chernobyl, Fukushima, and the slow violence of ecological decay.

Schwul sein kann schön sein! (Being Gay Can Be Beautiful!, 1980) confronts another taboo of its era. Members of the Homosexuellen-Initiative Wien (HOSI) ask passersby a simple question: Would you vote for a homosexual presidential candidate? Answers run the gamut from condemnation to apathy to cautious acceptance. For three weeks, the Vienna Festival hosts an information stand at Reumann Square, becoming a small but vital node of queer visibility. One woman interviewed calmly dismantles essentialist beliefs about gender, beauty, and relationship norms, insisting that all roles are socially constructed. Interviews with gay men foreground fear as a condition forced upon them: “It’s always the secrecy and anxiety that makes people distrustful.” The video reveals not only prejudice but also the psychological defenses it necessitates.

Part street theater, part ritual denunciation, Theatergruppe Collage – Autoanbetung (Car-Worship, 1980) critiques luxury automobiles as objects of modern idolatry. Performers in Satanic robes drag a car down the street, chanting hymns in which “God” becomes “Auto.” The satire is sharp yet sociologically acute: the automobile is not merely a vehicle but a sanctuary for the young, a mobile zone of privacy in an increasingly surveilled society, a new chapel of imagined autonomy.

Burggarten (1980) chronicles the conflict around Vienna’s famous public park, where youth sought free access to its grassy areas for conversation, music, study, relaxation, and open love, only to face resistance from law enforcement. Images of police brutality are intercut with sunlit greenery, starkly contrasting natural desire with the manufactured choreography of authority. Protest grows as violence intensifies, yet few Viennese seem aware of the escalating tension. The video ends without resolution, acknowledging the struggle beyond the frame.

The most intimate piece, Christa erzählt (Christa Recounts, 1980), presents a single shot of Christa, a Vienna prostitute, speaking plainly to the camera. As a child, she was shuttled between homes, her fantasies of stability crushed, before she entered sex work to support her own children. In unabashed testimony, she speaks of her ability to “switch herself off,” to reclaim her identity after work. Moreover, she argues (controversially yet grounded in lived experience) that it is better for men to visit prostitutes than pursue emotional affairs that tear families apart. Filmed without embellishment, her story becomes a mirror held up to a society that depends on the world’s oldest profession even while diavowing its existence in the same idiomatic breath.

Taken together, these works mark a moment in Austrian cultural history when alternative media became urgent, not merely for artistic expression but for the survival of civic consciousness. Volks stöhnende Knochenschau constituted a fragile but vital ecosystem of souls ignored yet essential to democratic life. Its power lies in refusing to polish the world into digestible narratives, instead presenting truth with the grain of experience left intact.

What the collective understood, and what remains true today, is that public reality is constructed through the circulation of images and words. When a state apparatus controls visibility, it tightens its grip not only on information but on the scope of thought. A counter-public, by contrast, expands the realm of the thinkable. It restores opacity to individuals rendered see-through. And so, the most radical gesture of Volks stöhnende Knochenschau is not its critique but its method: the relocation of agency from state institutions to ordinary bodies. The project insists that democracy must be lived from below and through bodies marked by desire, fatigue, refusal, and resilience.

In a media landscape still shaped by consolidation and algorithmic sorting, this archive echoes like a message smuggled from the past. Taken as a whole, it insists that history is not something broadcast from above but something we record, contest, and imagine together, one voice at a time.