Below is my review of two recent concerts led by Leon Fleisher under the title of the “Beethoven Concerto Project” at Cornell University’s Bailey Hall, May 7/8, 2011. The full interview excerpted therein follows.

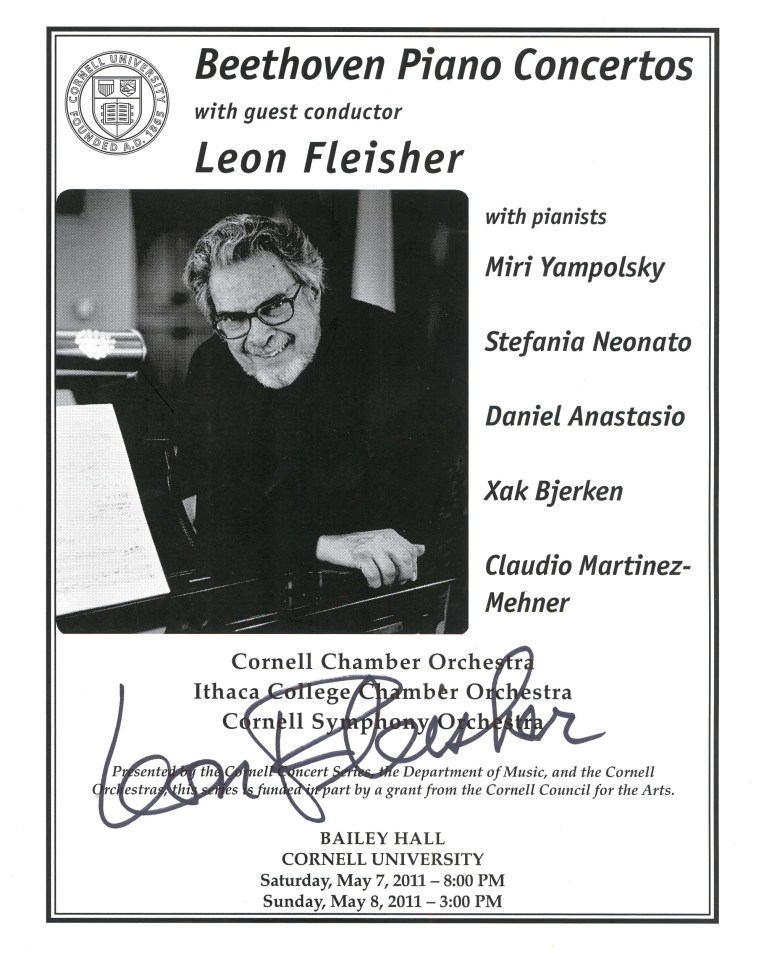

Leon Fleisher comes from a line of piano students extending directly back to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). Who better, then, than he to bring all five of the legendary composer’s piano concertos to the stage for a two-concert series? Fleisher is a legend in his own right, though one might never have suspected as much from the gracious humility with which he welcomed me to interview him last Thursday. In his speech I sensed a journey contoured with valleys and peaks in equal measure. At the highest of the latter, an illustrious career was suddenly halted when he was diagnosed with a neurological condition known as focal dystonia. This manifested itself in his right hand, two fingers of which curled under of their own accord. This might have undone him, were it not for an indomitable spirit and his prevailing love for the music that uplifted it.

Amid the storm of post-WWII pianists, many of whom were predisposed to strident showpieces, Fleisher had been quietly scrimshawing a more delicate niche into the yielding bones of the Austro-German canon. Very much a product of his teachers and their interests, as he will be the first to admit, Fleisher had settled into this repertoire without question, only to see it fade from his fingertips. One consolation: an altogether engaging body of work for the left hand paved the way for his reprisal on the classical stage. It was then that he began teaching, as well as conducting some of the world’s most prestigious orchestras. One unforeseen result of his activities at the podium was carpal tunnel syndrome, the corrective operation for which miraculously relieved his dystonic symptoms enough so that, with a measured combination of botox and Rolfing therapy, he has been able to play with two hands for the last fifteen years. Although he will never regain 100% functionality, his virtuosity and sensitivity have grown into something else entirely.

At a tender 82 years, Fleisher exudes a healthy balance of experience and resigned honesty. Refreshingly uninterested in the frills that so often creep into contemporary performance practice, he is more concerned with uncovering the music as it might have been, as it is now, as it may ever be. Not to be confused with an idealist, he is one who enjoys the proverbial moment, which remains the ultimate validation of all the practice and discipline that go into any performance. There is a peacefulness in Fleisher that one feels in his very presence, in his careful steps onto the stage, in the way he sits rather than stands, placing himself at a more familiar level with the orchestra before him, before us. His tempi are respectful, comforting, and never jarring, and his pianistic understanding of the music shines through with every swing of his hands.

(Photo by Susana Neves)

During our conversation, I asked Fleisher to share his thoughts about Beethoven, a composer with unfathomable staying power. “The remarkable thing,” he told me, “about Beethoven, I think, is the rate at which he overcomes the detritus, the residue of…bad performances. His success rate is extremely high. In other words, you can really play Beethoven quite badly, and still something very powerful will come through.” With this in mind, it only made sense that each concerto be presented to us by a different soloist. Not only did this allow the audience to hear more clearly the distinctions between the concertos, but also those between the performers, each of whom brought an idiosyncratic flair to bear upon the material at hand.

Miri Yampolsky, Fleisher’s former student, offered the most well-rounded balance of stylistic grace and sense of musical grammar in her rendition of the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, her buoyancy in the right hand foiled tastefully by a weighty anchorage in the left. Xak Bjerken—another former student and Yampolsky’s husband—brought his own unique grace to the keyboard, which lent itself beautifully to the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major. By far the most enigmatic of the set, this concerto, as Fleisher informed me, was once known among musicians as the “ladies’ concerto,” a tidbit of archival derision that has thankfully lost its currency. Fleisher himself prefers to see the Fourth as a middle-period dip for Beethoven into cosmological waters, a sonic foretaste of the metaphysicality that so pervades his final symphonies. Of all the players, Bjerken was most attentive to the baton, and one could feel his respect for the one holding it in every note he played. Italian-born Stefania Neonato had a fluid sense of timing of her own for the Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, heard most clearly in her trills and constantly running fingers. Not to be outdone was Spanish virtuoso Claudio Martinez-Mehner, yet another former student of Fleisher’s who filled the hall with palpable revelry in his rendition of the Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat. Also known as the “Emperor Concerto,” it more than lived up to this apocryphal nickname through the gallant expressivity that pervaded its realization at every turn. Yet by far the highlight to everyone’s ears, if the full-house standing ovation were any indication, was rising star Daniel Anastasio, a Cornell senior and student of Bjerken’s, who brought his finesse and prodigious talent to the stage for the Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor. So propulsive was his enthusiasm that it spurred him on prematurely, so that his chordal punctuations in the first movement did not always sync with those of the orchestra. Rather than see this as a detriment, I felt it as a sign of his exuberance. Both he and Bjerken continued the Fleisher lineage with due poignancy.

Readers of my past reviews will be all too familiar with my love/hate relationship with the house Steinway at Bailey Hall, but I am glad to report that the modest settings proved to be a fine sonic fit this time around. Martinez-Mehner in particular elicited more volume than I have ever heard from the selfsame instrument, a kinesis we saw reflected in his unbridled body language. Sometimes the relationship between soloist and orchestra is likened to a conversation. Yet in these concertos, at least, the piano was a conversation in and of itself, and the surroundings overwhelmed not a single word. As far as the three (!) orchestras were concerned, the results were variable. The Cornell players, in both their Chamber- and Symphony-sized incarnations, as Fleisher wittily related in our interview, were under the stress of finals: “They were sitting there playing, looking as dour and depressed as I’ve seen in any group in my life. I was so struck by it that I stopped and I mentioned it to them. I mean, here are young people in their late teens and early twenties, looking like they were all ready for the couch! And then one bass player said one word that explained it all: Finals. Poor kids…that’s not really what I think even the most refined education is all about. There has to be some joy in life. They smiled a bit after that.” As students who must balance primary academic commitments alongside their musical double lives, our Cornellians performed admirably well. And let us not forget the lovely Canzonas by Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1553/1556-1612), courtesy of the CSO Brass Choir, that bookended Sunday’s concert just outside the hall steps. That being said, the Ithaca College Chamber Orchestra was in a league all its own. Comprised of handpicked music students, it breathed like a single organism through superb tonal colors and communication. Regrettably, they lent their bows and breaths only to Anastasio’s performance, making it all the more electrifying.

“Like an EKG graph” was how my wife described the concerts. With her usual brilliance and fresh ears, she was able to cut through my verbose meanderings with a concise destination. For her, Beethoven is not about climax and resolution, but about the careful placement of clusters along an otherwise constant lifeline. I can only agree: Beethoven’s music doesn’t so much peak as plateau, navigating the nooks and crannies of a landscape that is bigger than all of us. This architecture was also reflected in the showings that preceded both concerts of Nathaniel Khan’s touching 2006 Oscar-nominated short film, Two Hands: The Leon Fleisher Story. In Fleisher’s testimony, we find something of a Beethovenian soul, one unwilling to let infirmity control the potency of its artistic license. As Fleisher so carefreely told me, when I asked about his being here, “It’s just a great adventure to go through with several of my former students. It’s a great delight to be able to come and explore the nature of this material with next generations. Plus, it’s fun, it’s what I do.” In the end, I could only bow to his candor, and by extension to the efforts of everyone who made this weekend possible.

(Photo by Joanne Savio)

Full interview with Mr. Fleisher, conducted by Tyran Grillo on May 5, 2011:

Having only just recently seen the documentary Two Hands for the first time, I am still struck by a comment you made regarding your connection to music itself—that it was perhaps the most important connection of all, something that had sustained you through hardships and ecstasies alike. And so, it is this connection that I would primarily like to discuss with you today. Before we get into that, however, I wish to ask one question in relation to your instrument: Have you come to hear the piano differently between the bench, the podium, and the classroom?

What an interesting question. I think I have to answer that “yes” and “no,” simply because, on the one hand—which would represent the “no,” I think—I hear in my head what I think is, for me, the ideal. In fact, that’s usually…well, I can explain the mechanism as I see it. On the other hand, as I actually listen to what’s being played, I think there is probably a difference between, let’s say, piano, orchestra, and students. I guess the main difference is whatever the medium is, whether it’s chamber music, solo piano, or orchestra. The idea of hearing—or listening, I should say—is an interesting one. The performer is, in fact, three people at the same time: Person A, Person B, and Person C. Person A, before he or she plays, must hear in the inner ear what it is that they’re going for, what their ideal is, so that they have a goal to strive for. If you put a key down without an intention behind it, it’s an accident, which means that the key that follows it is based upon an accident; everything that follows is based upon accident.

That reminds me of an art teacher who used to try to correct me from smudging as a method of shading. He used to say that a smudge is nothing more than a smudge the moment you run your finger across it. It just becomes an incidental mark without intention.

Oh, really? I can’t understand that. The smudge itself might be an intention…. So, that’s Person A. Person B is the one who actually does the playing, and has to be totally aware of how that playing is being manifested, so that if what Person C—who sits somewhat apart, who listens and judges—hears is not what Person A intended, Person C tells Person B, the doer, what to adjust to get closer to that ideal of Person A. And this is a process that goes on simultaneously and continually, all the time.

And, more broadly, do you feel that you changed over time as a listener?

Yeah, oh sure.

And do you think there is one change more than any other that has been deepest for you in your listening habits?

Well, I spent a good third of my life at the piano, which was essentially my instrument of choice, as it were, and most of the second third of my life, or a good part of it, dealing with orchestra, which is a beast of a totally different color. It’s really quite fascinating dealing with an orchestra. The response time on a piano is virtually instantaneous. In an orchestra, you have varying response times. I guess percussion is the most instantaneous, then strings. And you get varying responses out of winds and horns. Brass instruments respond later. And that’s just in terms of timing. Then you have timbre, instrumental differences. The one great advantage of the piano is that you can make it sound like an orchestra, and you can make it sound like the instruments of an orchestra. You can make it sound like a French horn or an oboe, cello…stuff like that. Yeah, it’s fascinating. Being a soloist is a very solitary affair, and therefore is full of what you might call the luxury of time. When you’re in your studio, however long you have to practice before you have to go about the rest of your life, that depends, but usually professional orchestras today rehearse for two and a half hours with a fifteen-minute break. That costs money, and you cannot go one second over time, because they’re paid in fifteen-minute segments. You go five seconds over and you have to pay them for fifteen minutes. So, dealing with an orchestra is, in a sense, more stressful, much more compact. It becomes very much a question, as with a doctor, of diagnosis and prescription. In other words, you have to be able to tell pretty much instantly what it is that’s not working, why this doesn’t sound the way you want it to sound. You have to diagnose the problem, and not with a certain infrequency do you find a conductor who from time to time misdiagnoses, who thinks the problem came from this or that player when in fact it comes from someplace else, and that’s usually when he loses the respect of the orchestra, because he can’t diagnose. And once you’ve made your diagnosis, you have to come up with the answer, with a prescription, to make it work. So, it’s a different kind of process. When you’re a soloist you have that luxury of time, you can try it this way and that way, you can ponder it, you have time.

(Photo by Joanne Savio)

Moving on now to Beethoven, I would like to field your thoughts on the series you are presenting here at Cornell, which is, of course, the Beethoven Concerto Project. Could you share your thoughts on the appeal of the concerto form and how the piano fits into its long history?

Oh, I think it’s very basic, if not primitive. It’s that age-old story of one against the many, and who’s going to trial. The poor, singular soloist…which is often emphasized if the soloist is of the feminine persuasion, making it even more appealing as a dramatic story. And then, happily, in the end everybody triumphs.

Some would say—and here I am thinking specifically of András Schiff—that the music of Beethoven is prone to getting lost under the residue of time and interpretation, and that one must try to “refresh” it, so to speak, with each new performance.

And how? Does he say how? [laughs] Does he pick up a hose and hose it down?

He tries, I think, to look at the score as much on its own terms as possible.

Yeah, I think that’s valid for whatever composer you’re playing. The remarkable thing, though, about Beethoven, I think, is the rate at which he overcomes the detritus, the residue of those bad performances. His success rate is extremely high. In other words, you can really play Beethoven quite badly, and still something very powerful will come through. Most other composers, if you play them badly, just become flat. But Beethoven, for some reason, manages to supersede, to…what’s the word I’m looking for…

Transcend?

…transcend even bad performances. I certainly agree with András, though I think it can be done with every piece of music. A piece of music, in a way, is an interesting kind of process. Because, like most art, in relation to the norm most great art consists to one degree or another of, and I use a very powerful word here, distortion, especially when compared to the norm. In the dimension of time in music, the norm would be, say, a metronome, which is a machine. It has nothing to do with the music. It merely measures the rate of speed. Many people think they have to play with that same regularity. So, in relation to the metronome, often what one does is a distortion. I mean, look at Michelangelo. People don’t have arms like that, you know? Or Giacometti, El Greco. People are not that thin, but certain types look that thin. So, distortion becomes quite important. However, once we’ve made the small distortion, it’s quite probable that after a few weeks we’ve gotten so used to that distortion that the meaningfulness of it has disappeared. So, well, let’s distort just a little bit more. Well, that’s satisfying again. And that lasts for a few weeks until we get very used to that. And so on, and so on. But every now and then, like the fisherman, you have to bring the piece out again and wash it down of all its barnacles, and all its distortions, and start again from scratch.

Going back to the idea of regularity…I’ve often heard people characterize the music of Mozart, for example, as being very regular, and that, in contrast, Beethoven’s shies away from repetition in favor of more free-flowing thematic cells and unexpected returns. Yet clearly, these are far from mere abstractions. What gives traction for you in the concertos specifically? What is their heartbeat, and how might we listen for it?

I always hesitate to give anyone signposts in a piece of music, because invariably it winds up that they just wait for those signposts and miss everything else, and it turns out to be quite a loss, if not a total loss. I don’t particularly subscribe to that thesis of Beethoven and Mozart…

It is, unfortunately, a common one.

Unfortunate, yes, and shares the meaninglessness of most things common.

It seems almost obligatory to characterize Beethoven as a deeply “troubled” and “dramatic” figure. By extension, his music has taken on a mythology of its own. We have, for example, this enduring association between the Andante of the Piano Concerto No. 4 and Orpheus taming the Furies before Hades…

Well, everybody brings to the music what they want to bring to it. I see No. 4 less as Orpheus and its attendant connotations and more as the Prophet talking to the multitude in the desert.

So when you have these personal images attached to the music, do you ever keep them in mind while playing or conducting, or are they just afterthoughts?

They’re usually afterthoughts. They give color. I think people really have to use whatever best serves them and best serves the music as seen through their eyes and as heard through their ears. In other words, it’s really quite pragmatic: whatever works. You don’t necessarily have to talk about it. You know, everybody has their way of, I think the phrase today is, “getting in the zone.”

Do you find any humor in these concertos?

Oh, they’re filled with it!

And how does it make you feel to engage with that humor, and do you try to bring it out?

I must say, I’ve been now at two rehearsals with various groups here, two groups so far, and I am going to meet today yet a third group. I was so struck last night at my second rehearsal, and I realized it was the same thing that struck me at the first rehearsal. It seemed to me that these young people were totally devoid of any humor. They were sitting there playing, looking as dour and depressed as I’ve seen in any group in my life. I was so struck by it that I stopped and I mentioned it to them. I mean, here are young people in their late teens and early twenties, looking like they were all ready for the couch! And then one bass player said one word that explained it all: “Finals.” Poor kids…that’s not really what I think even the most refined education is all about. There has to be some joy in life. They smiled a bit after that. And I think maybe by Saturday finals are over, so I look forward to some lighter spirit. No, this stuff is full of humor, and Beethoven’s humor is sometimes more on the rude side than most composers, though Mozart certainly has his share. You know, he has those famous scatological canons. The things we prudes of today scoff at were, back in Mozart’s time, just part of the regular scene.

I wanted to talk to you a little more about how music is received and how the fame of a composer might come into play in audience response. Take, for example, the Adagio of No. 5, which has been divorced as one of the finest passages in the set, if not in all of classical music. How do you approach these heartrending turns, so often plucked as sonic emblems? Do you treat them any differently, or do you prefer to see them as part of a larger whole and simply deal with them as they come?

The only extracurricular meaning that the second movement of the Fifth Concerto holds for me is that it was chosen by Lenny [Bernstein], for, uh…

“Somewhere”?

Yeah. [sings] “There’s a place for us…” He thought it was such a good tune that he used it for West Side Story. Stravinsky said: good composers borrow, and great composers steal. One might remark upon it in passing, but it certainly has no contributory virtues.

Now, these concertos are, of course, riddled with difficulties: the cadenza in the No. 3 Allegro, the pedaling in the Largo of No. 3…

That pedaling shows up everywhere, in virtually all the concertos. And the important part of it is the extent to which Beethoven’s indication is misunderstood, because he writes for the piano using the same term that is used for stringed instruments. It’s a totally different mechanism as manifested on the piano, and the effect is quite different. He writes senza sordino and con sordino, which on a string instrument is the extra little bridge you put on top of a normal bridge, the sordine, which mutes it to a certain extent. But the sordine on the piano is the damper, that bit of the mechanism made of felt that rests on the string that prevents it from reverberating. So when he writes senza sordino for the piano, it means lift those dampers so that the string can vibrate, can resonate as a result of being hit by a hammer, and the only way you can raise those dampers is to put the right pedal down. People cannot conceive that in Beethoven’s time he would want the resultant mix of harmony, which really belongs to impressionist music, which comes much, much later. But they don’t realize that on these pianos today you get much more reverberation from using the right pedal than you did in Beethoven’s time, so if you want to approximate the sound that he seems to be asking for when he writes senza sordino, you can get it by just using a fraction of the pedal, not putting it down all the way but just barely depressing it so that the dampers lift just the wee bit off the string, and you get this kind of hazy recollection, remembrance of things past, in this sound that he was obviously going for.

Beyond the written score, do you feel there are any particular challenges that await the would-be Beethoven performer?

The concertos certainly do not span Beethoven’s life’s output the way that, say, the sonatas do. They stop at opus 73, and his works go up to something like 135. So the first two are really youthful. Actually, what we call the Second Concerto, the B-flat, is really the first. He wrote it before he wrote the C major. It was just published after the C major was published. The other three are middle period pieces of quite different characters. Yes, in a sense the Fourth, which was for a long time called the “ladies’ concerto” because it wasn’t as outgoing, as…what’s the opposite of introspective?

Extroverted?

Extroverted, thank you. The Fourth being more introspective, in a sense dealing with the transcendental, dealing with the sublime. Those are challenges that you find in all of Beethoven, that he likes to delve into the cosmos, which evokes the wrong picture. He likes to explore the universe. His music really becomes quite metaphysical. He is interested in those great questions of how we relate to the world around us, how are we like a brook, how are we like the leaf on a tree. French music is more concerned with the sensory, with the senses—with sense of smell, touch, taste, sight as seen through squinted eyes. Russian music is a much more subjective kind of breast-beating: look how I suffer…

More embodied, perhaps?

Yeah. But German music, as demonstrated by Beethoven, really is metaphysical. It raises those existential questions.

So, you mentioned that the Fourth was once known as the “ladies’ concerto,” which reminds me of the research I am conducting now on the differences in audience expectations toward female and male classical pianists, and I wonder what gender stereotypes you see still lingering on the stage in that regard.

I think we’re getting, thank God, over those to a great extent. I should even stop talking about the fact there was a period of history when the G major was known as the “ladies’ concerto.” It injects something that has no role, no place. Some of our female performers are just…someone like Martha Argerich is just a force of nature. It just blows everyone and everything away when she makes music.

And I’m sure that anyone just listening to her play on a recording would never think to question her gender. It’s not important.

Oh no, of course not, of course not.

Surely, I am not alone when I express my adoration for your Brahms concertos as reigning favorites in your repertoire. I feel your passion and connection to that music quite viscerally when I listen to or watch it, and I wonder if your relationship with Brahms is particularly different from that with other composers.

I had the incredibly great fortune of working with one of the great masters of the twentieth century, Artur Schnabel, and my love and appreciation for the music that most interested him, which was essentially German music…yeah, I come by that quite legitimately. My bloodlines are Russian, and one of my great early influences was French. I feel I’ve had the best of all worlds, musically.

Is there one mantra, word of wisdom, philosophy, or lesson from your teachers that you still carry with you?

No. I am, to an extraordinary extent, the result of my teachers, and they were filled with nuggets.

What does it mean for you personally to be here at this place, at this time, with these friends and colleagues, presenting this music?

It’s just a great adventure to go through with several of my former students. It’s a great delight to be able to come and explore the nature of this material with next generations. Plus, it’s fun, it’s what I do.

I think I speak for all of us when I express a deeply felt and genuine gratitude for your presence here this week and for bringing what I am sure will be wonderful performances.

Well, I don’t know about that [laughs]. We will have had, in a sense, only minimal rehearsal. It is a bad time of year for the students, being finals time, so I’m not sure if they’ll have their best concentration. But again I think Beethoven, as always. will somehow muddle through.

He will prevail?

[laughs] Yes, he does, he does prevail.