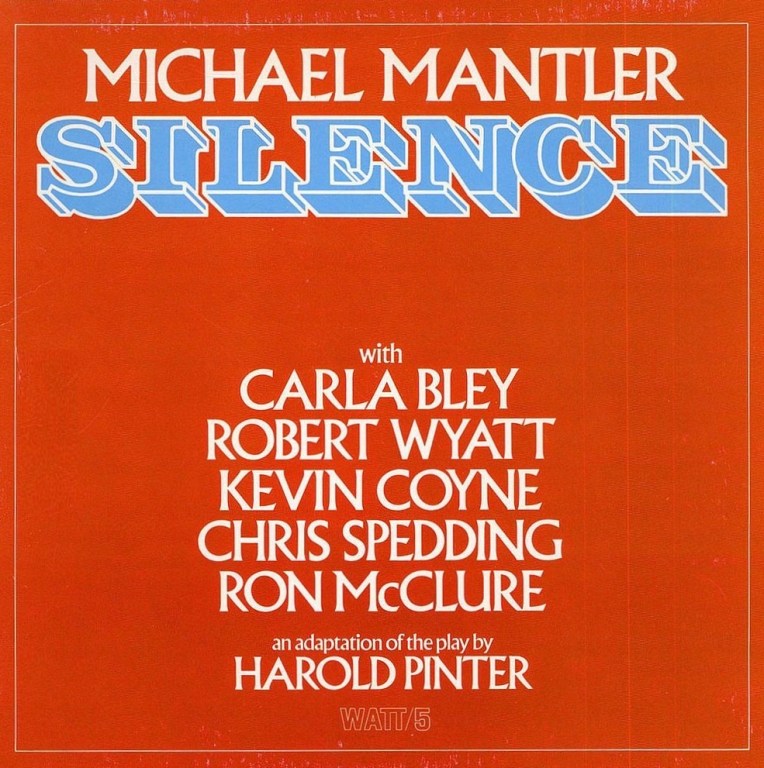

Michael Mantler

Silence

Robert Wyatt voice, percussion

Carla Bley piano, voice, organ

Kevin Coyne voice

Chris Spedding guitar

Ron McClure bass

Clare Maher cello

Recorded during January 1976 at Grog Kill Studio, Willow, New York

Engineer: Michael Mantler

Robert Wyatt and Chris Spedding recorded during February with the Manor Mobile at Delfina’s farm, Little Bedwin, Wiltshire, England

Engineer: Alan Perkins

Kevin Coyne recorded during April with the Virgin Mobile at the Gong Farm, Whitney, Oxfordshire, England

Engineer: Steve Cox

Additional strings recorded during June and mixed during November at Grog Kill Studio

Engineer: Michael Mantler

Produced by Carla Bley

“One way of looking at speech is to say that it is a constant stratagem to cover nakedness.”

–Harold Pinter

Upon waking from the fever dream of Michael Mantler’s The Hapless Child, we might be forgiven for expecting reality to welcome us back with comforting arms. Instead, Silence throws us into the bore of everyday life, so that by the end we’re left wondering why anything that mattered ever mattered at all. In this musical, though far from incidental, setting of the eponymous play by the ever-contrarian Harold Pinter, we find ourselves in the company of Rumsey (Kevin Coyne), Ellen (Carla Bley), and Bates (Robert Wyatt). Rumsey is brash and self-confident, happy to have a girl on one arm—“She dresses for my eyes,” he sings—and a blissful disregard for mortality on the other. The environment Mantler composes around him creeps in with inevitable foreboding. The dialogue, such as it is, is more internal than external, chillingly honest yet indifferently expository. Ellen, for her part, is possessed of a breezy self-awareness: “There are two. One who is with me sometimes, and another. He listens to me. I tell him what I know.” In so saying, she reveals a hidden motive to the relationship, a conduit between souls that shrivels in fear when Bates enters the scene and brings with them a bevy of piano, bass, and percussion. All of which sets off a chain reaction of circular reasoning that muddies more than clarifies the human condition.

The music is a mixture of rock, funk, downtown cool, and European art song. Without it, there might be nothing to hold on to. Guitarist Chris Spedding is remarkable, gaining deepest traction in “She Was Looking Down,” and Bley lays on a thick layer of expressiveness, both as pianist and as vocalist (note, especially, “After My Work Each Day”). But while this is as luscious and engaging as any Bley/Mantler collaboration from the 70s could be, the play itself is lackluster to say the least. Its theme of lost souls is as fatigued as the characters it threads like beads on a necklace far too big for its own neck. As the drama develops, memory overlaps and all sense of time stops, unravels, and expands. But any pretentions Pinter might have of making an existential statement fall flat for me, especially when compared to the stripped-down brilliances of Samuel Beckett and Edward Gorey that preceded it. That said, in relatively short bursts—as in “When I Run” and “A Long Way”—the dialogue is somewhat tangible. The best example is “Sometimes I See People,” which creates a charmingly metaphysical atmosphere for being so much about music, sensory experience, and sense of belonging. But really it’s Mantler’s stage, rather than the people ambulating across it, that keeps me from walking out.

Both realms, the play and this soundtrack, are cyclical constructions. But if the words are just a spiral, the music is a helix. It binds with our DNA and finds a place in our evolution as listeners.