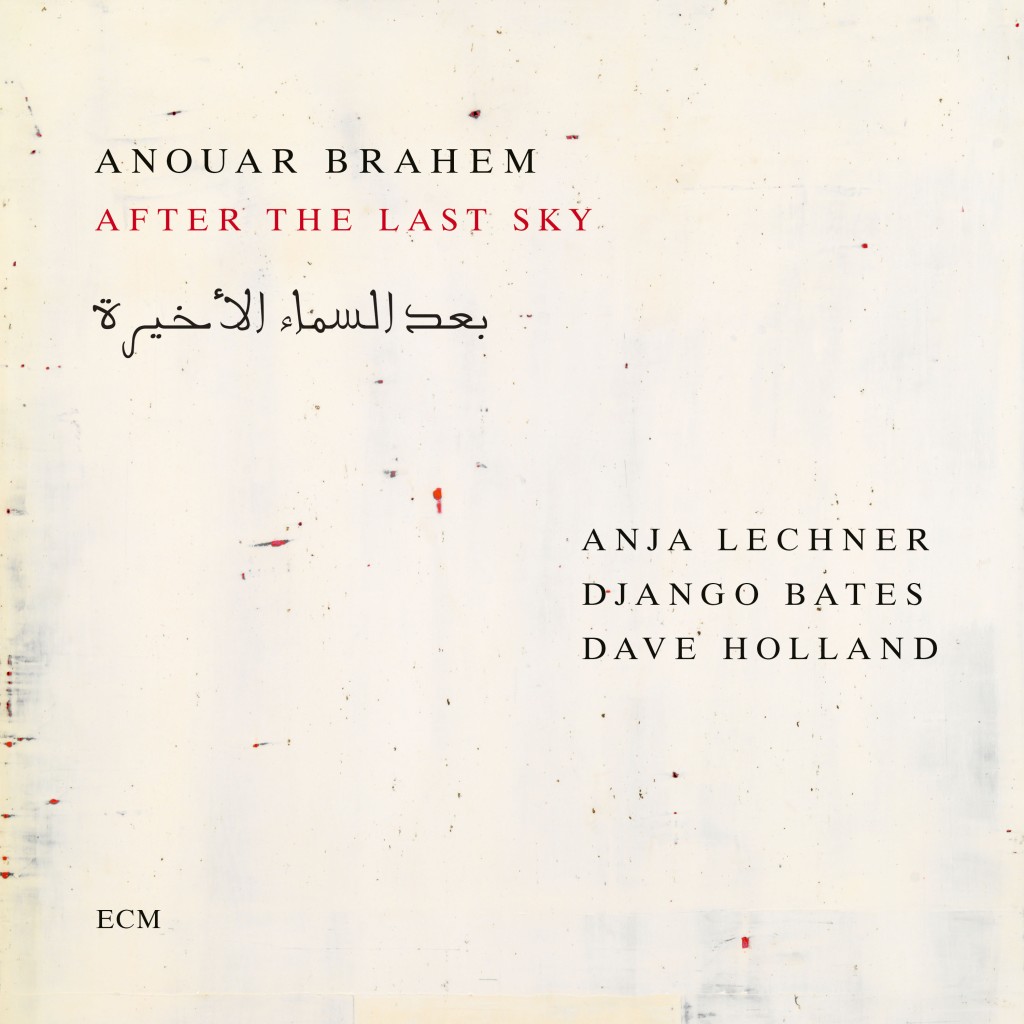

Anouar Brahem

After The Last Sky

Anouar Brahem oud

Anja Lechner violoncello

Django Bates piano

Dave Holland double bass

Recorded May 2024

Auditorio Stelio Molo RSI, Lugano

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Cover: Emmanuel Barcilon

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: March 28, 2025

Where should we go after the last frontiers?

Where should the birds fly after the last sky?

–Mahmoud Darwish

After The Last Sky marks the return of oud virtuoso and composer Anouar Brahem to ECM, eight years after Blue Maqams. That groundbreaking album also featured pianist Django Bates and bassist Dave Holland, both of whom are retained here, along with a new addition in cellist Anja Lechner. The result is a culmination of culminations, blending Brahem’s evolving integrations of jazz, European classical music, and, of course, the modal Arabic maqams at their core. Gaza was firmly on his mind leading up to and during the recording, and the titles reflect this awareness in a contemplative way. Despite the music’s delicacy (if not because of it), it offers prescient meditations on the horrors of violence that, sadly, seem to be the most inescapable leitmotif in the symphony of our species. That said, Brahem is not interested in proselytizing. “What may evoke sadness for one person may arouse nostalgia for another,” he says. “I invite listeners to project their own emotions, memories or imaginations, without trying to ‘direct’ them.” By the same token, notes Adam Shatz in his liner essay, “as with ‘Alabama,’ John Coltrane’s harrowing elegy for the four girls killed in the 1963 bombing of a Black Church by white supremacists, or ‘Quartet for the End of Time,’ composed by Olivier Messiaen in a German prisoner of war camp, your experience of Brahem’s album can only be enhanced by an awareness of the events that brought it into being.” Either way, After The Last Sky invites us into a conversation between ourselves and the political realities we would rather avoid.

And so, when wrapped in the tattered garment of “Remembering Hind” to start, we must remind ourselves that music, like life, is only what we can experience of it. If something never enters our sphere of awareness, it might as well not exist, which is precisely why we so often choose to ignore rather than engage. Here, we are given a space in which to reconcile those two attitudes, in full recognition that the sacred is forged from the ashes of the profane and that beauty is a fragile compromise for destruction. In some ways, this contradiction is inherent to Brahem’s instrument and its vulnerabilities, which he animates from within.

The more we encounter, the less we can deny our complicity in suffering. Whether in the post-colonial shades of “Edward Said’s Reverie” or the painful imagery of “Endless Wandering” and “Never Forget,” the weight of exile weighs on our shoulders. Meanwhile, the instruments take on distinct personas. Bates is the bringer of prayer, Holland is the bringer of faith, and Lechner is the bringer of community. Through it all, Brahem is the one who brings trust. Through his establishments, he reminds us that intangible actions have very physical consequences. By the thick threads he pulls through “In the Shade of Your Eyes,” we draw close for comfort in the afterglow of bombs.

Despite the sadness casting its pall over this journey, there are way stations where gravity has less of a hold on us and where, I daresay, hope becomes possible again. This is nowhere truer than in “The Eternal Olive Tree,” an improvisation between Brahem and Holland. As bittersweet as it is brief, it finds the oudist feeding on the bassist’s groove as if it were a ration to be savored, not knowing where sustenance might come from next. Other sparks of resignation are carefully breathed upon in “Dancing Under the Meteorites,” “The Sweet Oranges of Jaffa,” and “Awake.” In all of these, Lechner’s playing transports us to another level, inspiring Brahem to dramatic improvisational catharsis (yet always restrained enough to maintain his sanity). The album ends with “Vague.” Among his most timeless pieces, it is lovingly interpreted. Bates renders the underlying arpeggios with artful grace, while Holland and Lechner open the scene like a hymnal for all with ears to hear.

I close with another quote from Shatz, who writes: “Brahem’s album is not simply a chronicle of Gaza’s destruction; but its very existence, it offers an indictment of the ‘rules-based order’ that has allowed this barbarism to happen.” Thus, what we are left with is an indictment of indifference, as profound as it is melodic. What Brahem and his band have done here, then, is not to simply make an album of beautiful music (which it is) but rather to offer themselves as a living sacrifice to the altar of reckoning to which we all must bow if we are to make a difference that matters. When we are stripped of all we have, music is what remains.

We saw Anouar Brahem play on his last visit to London in November. Billed as the Anouar Brahem Quartet, the concert turned out to feature the Anouar Brahem Trio. Quite early in the performance, the oud maestro explained why. His percussionist, Khaled Yassine, had been forbidden to leave Lebanon by the Israeli occupation forces. Brahem’s tender concern for his friend and themes drawn from “After The Kast Sky” amplified, without proselytising, the need for all of us to enter that conversation with political reality.

Thank you for sharing this story, Ian. The follies (and horrors) of politics impact so many facets of our lives, including the freedom of expression through art. What a testament to those like Brahem who seek to regard the larger human picture when the world just wants to place suffering on a hierarchy of concern.