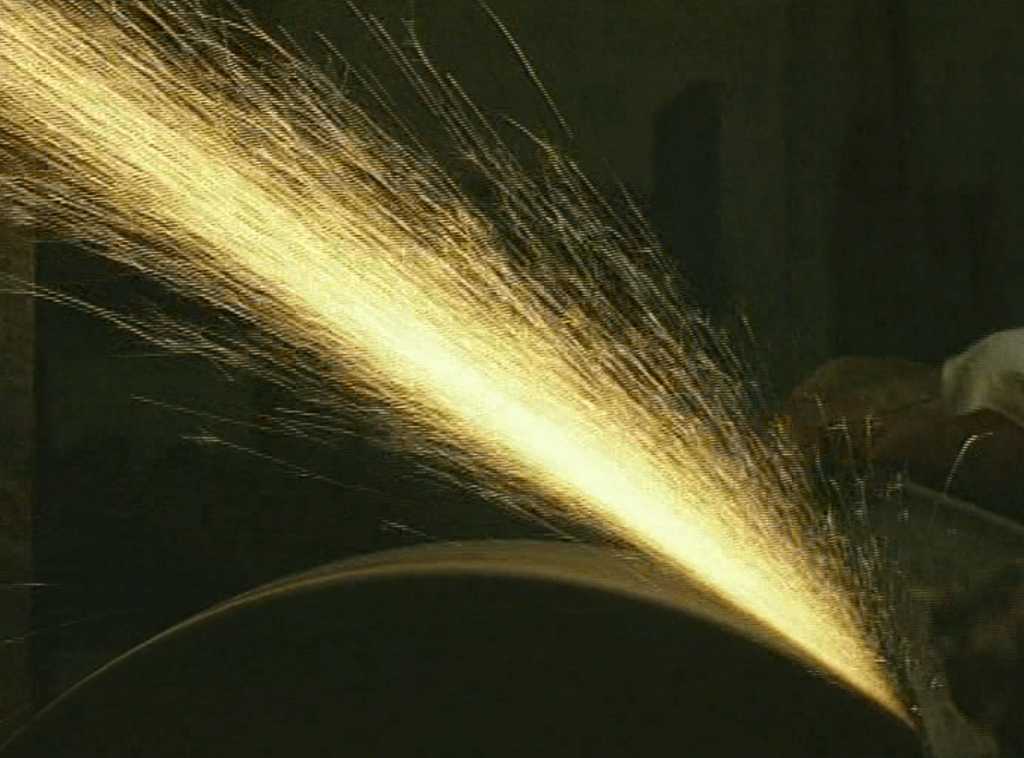

Gertrude Moser-Wagner may be known primarily as a sculptor, yet her videos reveal an artist who treats moving images as material phenomena rather than narrative devices. Her formula of “concept and coincidence” is not merely a method but a worldview. Concept is the structure she brings to a site. Coincidence is what the site returns. Her films emerge from the friction between intention and accident, between the framework and the world that slips through its seams. Out of that friction rises the “spark” she often speaks of: the moment when place, sound, body, and camera discover a shared frequency, and experience begins to vibrate in multiple layers at once.

Although her practice ranges across sculpture, installation, performance, and collaborative happenings, her videographic creations remain deeply tactile in their orientation. She treats image as substance, sound as atmospheric pressure, and location as something that must be excavated. Each frame feels unearthed rather than staged, a found object transformed through the conditions of its encounter. This timely DVD, which collects works made between 1987 and 2000, serves as a kind of field notebook, a record of embodied perception. These films do not illustrate ideas but reveal how ideas collide with the textures of real spaces.

The first of these encounters, Lingual (1992), opens with a startling gesture of intimacy: a calf sucking on a human hand. Instead of barnyard ambience, organ pipes fill the air, lifting a primal act into ritual space. Josef Reiter’s sound design turns ingestion into ceremony. The film becomes an exploration of how the world is taken in long before it is spoken. Moser-Wagner compresses the image into narrow, constricted views and then releases it into the full frame, creating pulses of tightening and release. The effect is haunting in its simplicity, suggesting that language begins as touch and that meaning, before it can be articulated, must first be felt.

That sensitivity to spatial breath intensifies in Kiosk (1993), filmed in Skoki, Poland, inside a villa whose architecture seems to fold in on itself. The title is an anagram of the town’s name, as though the building had been scrambled into a linguistic echo. Again, Reiter collaborates on sound, this time evoking the hum of bureaucratic machinery, including ticker tape, typewriter keys, and mechanical exhalations. The imagery, predominantly black and white but punctuated by uncanny bursts of color, transforms the space into an architectural hallucination. Stone windows tilt and stretch, as if the house were confessing its own interior life.

In Luftloch (1987), filmed at St. Lambrecht monastery in Styria, Austria, concept and coincidence intermingle with palpable immediacy. Musicians Andreas Weixler and Se-Lien Chuang generate an aural landscape that interweaves with images of industrial scrap, abandoned buildings, tai chi-esque movements, and bodies echoing through forgotten spaces. The film oscillates between document and spontaneous happening. A communal meal surfaces, then a staircase, then water, then a video of a woman eating fish. Industry seeps into monastic quiet. At one point, glass shatters against concrete; at another, the camera peers through a small aperture onto the street outside, holding interior and exterior together like two lungs sharing a single breath. The entire piece feels sculpted in real time, a performance inscribed into the environment.

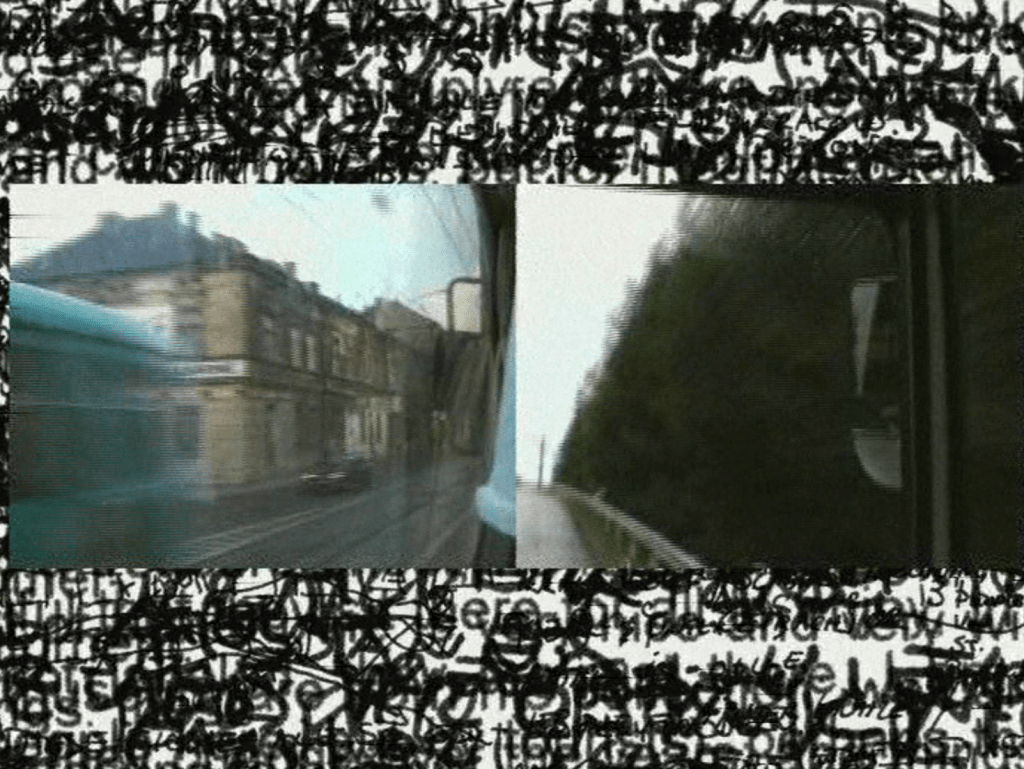

Collaboration unfolds differently in Vice Versa / Kraków–Krakau (1998), made with Beverly Piersol. Here, the artists investigate the uncanny linguistic connection between Kraków in Poland and Krakaudorf in Styria. Traveling to both places, they exchanged daily impressions by fax and phone, sending fragments of thought, weather, conversation, and miscommunication. The video is divided into a split-screen dialogue: interviews with a former mayor on one side, drifting landscapes on the other. Faxes, scribbles, and handwritten notes accumulate like sediment across the images. The screen becomes a palimpsest, a layered body of textual and visual residue that foregrounds the limits of naming. Two places share a name but not a destiny. Two artists share impressions but not a home. Language fails even as it connects.

In Ouroboros (2000), Moser-Wagner narrows the gaze on an existential scale. The subject is ROL6, a genetically altered nematode that, once stripped of a particular gene, moves only in circles. Its life becomes a loop without deviation, a literal ouroboros. Andreas Weixler builds a soundscape from Moser-Wagner’s intoned repetition of the title, creating a drone that hypnotizes and unsettles. Under the microscope, the tiny creature turns endlessly, a biological machine fulfilling a script it cannot escape. Yet through Moser-Wagner’s lens, the worm becomes a cosmic figure, a miniature emblem of human existential loops, an organism embodying the tension between agency and determinism.

These films suggest that every act of perception is a negotiation, a delicate interplay between the structural and the spontaneous. Moser-Wagner’s camera collaborates with space rather than controlling it. Meaning arises not from clarity imposed but from fragments, textures, accidents, and atmospheres. The calf’s tongue on a hand, the villa tilting in memory, the monastery breathing through its corridors, the twin cities of Kraków and Krakaudorf speaking across distances, the nematode turning in its microscopic orbit—these are not interruptions but invitations. Each reveals where our conceptual scaffolding falters, letting reality slip in through cracks we did not know existed.