Trauma, Erotics, and the Phantasmatic Image

Hans Schifferle once described Dietmar Brehm’s cinema as a “psychothriller,” a space where horror and sexuality converge in unstable proximity. The term captures both the themes and the underlying structure of his work. Brehm explores the anxiety between erotic fascination and forensic inspection, unfolding one involuntary memory at a time. His background as draftsman, painter, photographer, and collector of images shapes his approach. He draws on decades of accumulated material, ranging from documentaries to action films, ethnographic footage, and pornography. Much of it is anonymous, never intended for circulation. Authenticity remains uncertain, as any scene that appears salvaged may just as well be staged. The results inhabit the uncertain boundary where truth and fabrication lose distinction.

The Black Garden cycle, created between 1987 and 1999, is the clearest expression of Brehm’s aesthetic, through which he distills psychic trauma into bursts of arrhythmia. He explores the conflict between the urge to look and the fear of what the eyes might uncover.

The Murder Mystery (1987/92)

A storm soundtrack establishes an external threat. Images shift between a body placed in a field, a woman receiving pleasure, and a man in sunglasses whose stare stands in for our own. Spatial cues appear and fade. Rooms blur. Bodies change into objects, and objects hint at concealed bodies. The montage forms an interrupted rhythm that never stabilizes. Watching becomes an anxious search for coherence that always slips away.

Blicklust (Desire to Look) (1992)

Introspection takes the form of dissection. A drawing of a dissected eye signals that vision itself is under strain. A bound woman, surgical procedures, a hanging body, insects spiraling toward light, and quiet water form a vocabulary of exposure. Voyeurism manifests with unsettling proximity. Intimacy leaks into pathology. Looking becomes a cut that both reveals and harms.

Party (1995)

An electronic voice announces, “Good morning. The time is six a.m.,” as if awakening the viewer into a misplaced body. Scorpions fight while a man urinates, brushes his teeth, and washes his face. A woman touches herself. Shadow puppets appear. Exaggerated musculature emerges and vanishes. The human and the animal intersect in a series of gestures that suggest control, threat, and self-contact. The scorpions’ combat externalizes Geertzian tensions that haunt the scenes.

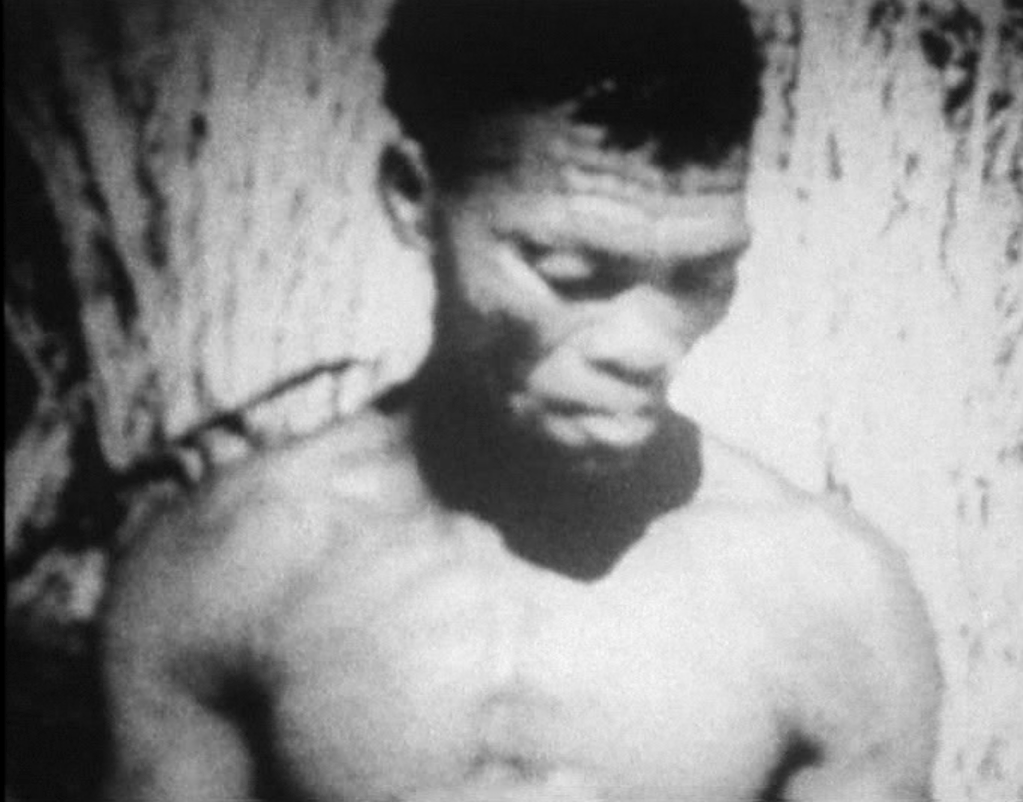

Macumba (1995)

The cycle’s most troubling work. Rain provides a sonic surface for images of Black pornography, African hunting footage, and scenes of animal violence. The phallus becomes aligned with pursuit and killing. While the critique of racialized eroticization is evident, the repetition of these images works against itself, collapsing into reenactment. Here is a vortex where representation and violation intermingle.

Korridor (1997)

Footage found in an old Vienna shop gives this one the feel of an accidental confession. Scenes of a man and woman in bed alternate with exterior shots of anonymous buildings. Birdsong and indistinct conversations drift across the soundtrack. A tree against the sky frames the beginning and end. The couple’s intimacy floats without context, unanchored. They seem to inhabit a corridor between identities and moments, never fully present in either.

Organics (1998/99)

The final film gestures toward female centrality, although any semblance of protagonism fades quickly. Masks, explosions, self-pleasuring, X-rays, surgeries, and architectural fragments emerge in clusters that never settle. A stalking gaze tries to impose order but only deepens fragmentation. The result recalls dream sequences by Guy Maddin, though interrupted by abrupt sexual imagery.

Coda: On the Edge of the Unbearable

Brehm seeks no clarity or comfort. His 2000 interview confirms that he creates for himself, guided by instinct rather than audience. This independence gives the work its raw intensity, but it also produces a physical unease that can be difficult to endure, operating at the point where fascination turns into revulsion. Their power arises from that tension.

Black Garden offers no catharsis. It exposes the viewer to a world where eroticism and violence intertwine, where desire corrupts memory, and where bodies function as both sites of longing and threat. The experience lingers not in the intellect but in the nerves, abstract and unmanageable.

What complicates the cycle most is the risk it poses. By assembling images of objectification, especially those involving racialized bodies and women, without a counter-perspective or contextual grounding, they can slip into the very aesthetic of domination they seek to deconstruct. Since much of the footage is drawn from archives of harm, and since Brehm refrains from introducing reflective distance, he sometimes underscores rather than undermines. And so, we are left holding a double-edged sword, one that illuminates the pathology of the gaze and also demonstrates how difficult it is to represent that pathology without repeating it. It also exposes the cost of entering such terrain without safeguards.

Perhaps this is why Black Garden lingers. It does not resolve the unconscious but reveals its pressure points. It invites us not to interpret but to withstand, to remain inside the tremor where desire becomes fear and where the act of looking exposes the viewer in return.