A Story of Paranoia, Patriarchy, and the Unmaking of Reality

VALIE EXPORT’s Invisible Adversaries (Unsichtbare Gegner, 1976), created with Peter Weibel, occupies an unsettled corner of postwar Austrian cinema, a place where fiction, visual essay, performance, and feminist critique converge into one restless organism. Amy Taubin once said of it: “The film feels a little as if Godard were reincarnated as a woman and decided to make a feminist version of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” EXPORT indeed reshapes the paranoid science-fiction template into an intimate psychodrama that charts a woman’s body under siege by media, lovers, the state, systems of communication, and the titular unseen forces that sustain social norms at the expense of eliminating deviations from it.

For EXPORT, the body does not sit within space. It is space, a field of ions charged by the friction between self-expression and its potential eradication. She strips away social clothing not to reveal some almighty essence but to embrace a corporeal vocabulary that refuses translation. Her own writing guides the mood at hand: “[W]hen children become enemies, the object is no longer testing a theory of existence but salvaging individuation, bare existence in a reality of senseless destruction (even at the price of exclusion).” Communication writ large, in her view, is a vehicle for hate. The film stretches this thought until language, images, and relationships split open under the strain.

A Year in Anna’s Life

At the center stands Anna, played with elegant dissolution by Susanne Widl, a photographer retreating into morbid subjects and unsettling acts of looking. While EXPORT writes her scenes, Weibel plays her partner, Peter, and composes his lines, an authorial split that sharpens the conflict between male and female subjectivities.

The first images signal that truth has already been damaged: the title appears on a crumpled newspaper as a tide of electronic noise fills the soundtrack. Even before the story has begun, the world is slightly off. A radio next to Anna’s bed cuts into routine news with a bulletin announcing the return of an alien force known as the Hyksos, who assimilate humans through radiation. They resemble everyone else. They are already here. Their apparition is treated not as science fiction but as a metaphor for xenophobia, fascism, and the unaddressed violence within Austria’s own history.

The camera drifts above the city as if pulled by a force Anna cannot name. Her phone rings, but there’s no voice on the other end. She applies makeup while her reflection moves independently, the mirror claiming her gestures. The scraping of the foundation becomes a small wound. Meanwhile, a man kneels to lick the street. EXPORT stitches these images together with abrupt force (a short interlude recalls her earlier Mann & Frau & Animal as Anna develops photographs of female genitalia while a man retches offscreen). Women adopt poses from religious paintings, gestures sculpted by myth rather than intention.

Love as Labor, Labor as Love

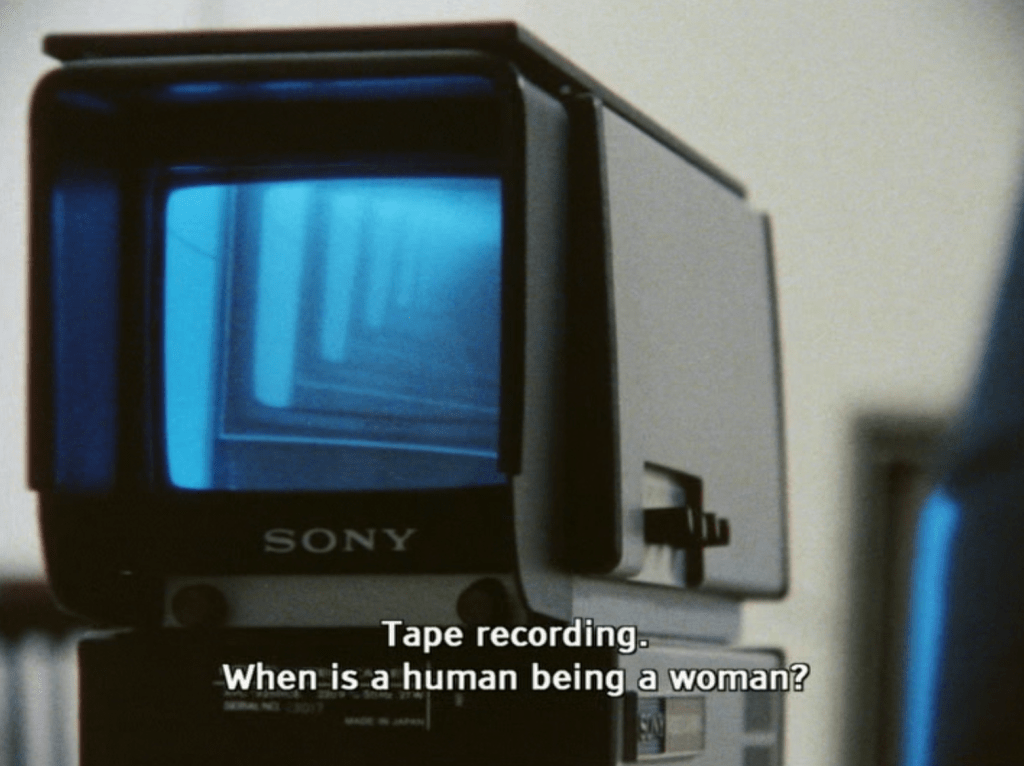

Anna and Peter share brief moments of closeness, yet even tenderness carries an undertow of alienation. Photographs freeze their entangled bodies, placing the camera between them. Later, in the bathroom, Anna muses on Lévi-Strauss and the mythic body while the mirror divides her into two. She shoots on the street, then overlays her body onto further sacred imagery through a television monitor, rewiring art history with her own silhouette.

The city tightens around her. “If you are creative in Vienna,” she says, “the police suspects you.” Her remark widens into a critique of Austria’s broader resistance to artistic and social dissent. Men hungry for authority drift into both Anna’s and Peter’s lives. While she cooks, Peter complains about the conditions at home, revealing his expectation that her labor remain invisible. She accuses him of disguising selfishness as political rebellion. Their dispute expands until every phone call she makes reveals a household in disrepair, each one locked in its own argument. EXPORT cuts to battle footage, collapsing domestic turmoil into a wider field of vehemence. Anna then becomes a photograph lying on the ground, her body reduced to an image without agency.

A Descent into Unreality

Anna’s unraveling quickens. She slices through the objects on her table, then through living creatures, as though dissection might yield a truth withheld. When she opens the refrigerator, a living baby stares back, and taped to the door is her own face. Every threshold circles back to herself. Her photographs become more severe: excrement, disabled children, demolished buildings, wrecked vehicles. She sets fire to an image of the ocean, erasing even the idea of calm with its opposite.

“Life is just a series of reflections,” she says. At a café, Peter insists he is the one protecting her from her thoughts. She answers with a question: Why must she impose herself against the defiance of reality? He condemns men in power yet cannot recognize his own relation to it. When she tells him the Hyksos have already bought him, he calls her paranoid. After he leaves, she lights a small fire in a foil bowl. A quiet gesture of defiance.

Communication Becomes Catastrophe

Anna’s ears grow sharp to every disturbance. The rustle of newspaper pages becomes unbearable. Words feel like blades. At night, Peter reads from an old manual of sexual positions. Its mechanical tone exposes the banality of hormonal scripts. Anna trims her pubic hair and shapes it into a moustache, a flicker of humor and gender play that mocks every role she has been assigned.

Peter lectures her about domestic habits, insisting he is merely stating facts. EXPORT thus reveals a twisted heart in his claim to neutrality. In their apartment, television monitors return their faces with a slight delay, multiplying their argument into grids of disconnection. Anna feels reality itself slipping into disguise. On a train, she moves with broken rhythm, and later, in a night scene, she cries while men masturbate around her. Society is already coming apart in every sense of the word.

Double Vision

She visits a doctor, hoping for clarity. He recommends psychotherapy. She photographs him instead. When she develops the image, his face appears doubled, confirming the Hyksos’ presence. He rejects her conclusion, trapped in the logic she has already abandoned. At a cinema, she watches footage of war and genocide, her personal crisis merging with the collective trauma.

One night, she dresses carefully, lies in bed, and listens to the radio. The camera withdraws slowly. No one mentions the Hyksos. The world continues as if nothing has occurred, which is the most chilling detail of all. Hands then tear a photograph of the scene, as though the film itself must rip apart its own reality to breathe.

A Story of Becoming Unrecognizable

Invisible Adversaries does not depict paranoia but performs it until paranoia becomes a mode of existence. Repetition is the tenor of oppression.

Anna’s journey is not a plunge into madness but a lucid reckoning with a world arranged to make women feel mad. The Hyksos are not a singular enemy. They represent every force that infiltrates the female subject: ideology, imagery, relationships, institutions, and communication itself. EXPORT asks what it means for a woman to experience her life as an invasion. Anna’s answer, played out across fractured montage and a life ever on the brink of dissolution, is devastating. The only response worth trying is to tear the picture apart and breathe.