Depiction is a crime is an attempt to collapse television, performance, sculpture, and linguistic play into a single, unstable medium. These creative experiments and performances, made in the infancy of video art, hinge on artist Peter Weibel’s conviction that representation itself is a form of violence. “The price of a picture,” he warns, “is sometimes a victim.” His works are not elegies to that violence but exposures of it, seizing television from its role as an unexamined transmitter and repurposing it as a laboratory for dissecting perception, identity, and the politics of communication. As Hans Belting notes, Weibel wanted “to claim TV for art, something which had little if anything to do with simply presenting art on television.”

The program begins with Publikum als Exponat (The Public as Exhibit, 1969), where the gaze is rerouted and weaponized. Exhibition viewers are interviewed, their faces framed and displayed as part of the exhibition itself. By the end, the museum guards intrude, reminding us that surveillance and cultural authority blur all too easily. The camera’s red light is the new spotlight: whoever stands before it is instantly aestheticized, catalogued, and judged.

From there, Weibel plunges into his “tele-actions,” a series of interventions designed to reveal television as a tyrannical box that disciplines both the broadcast and its viewers. In Mehr Wärme unter die Menschen (More Warmth Among Human Beings, 1972), the artist strikes matches against abrasive strips taped to a woman’s wrist, neck, and crotch. It is both erotic and mechanistic, tenderness exchanged for friction.

Abbildung ist ein Verbrechen (Depiction is a Crime, 1970) stages a duel between a Polaroid camera and a television camera. The Polaroid fires—an image-capture as a gunshot—and instantly the video feed goes black, as if killed. Then the Polaroid develops, slowly revealing the camera crew, their ghostly appearance mocking the supposed immediacy of both mediums. This pivots into Intervalle (Intervals, 1971), where the distance between the monitor and a sine tone becomes the subject: a study of audiovisual geometry in which technology measures itself.

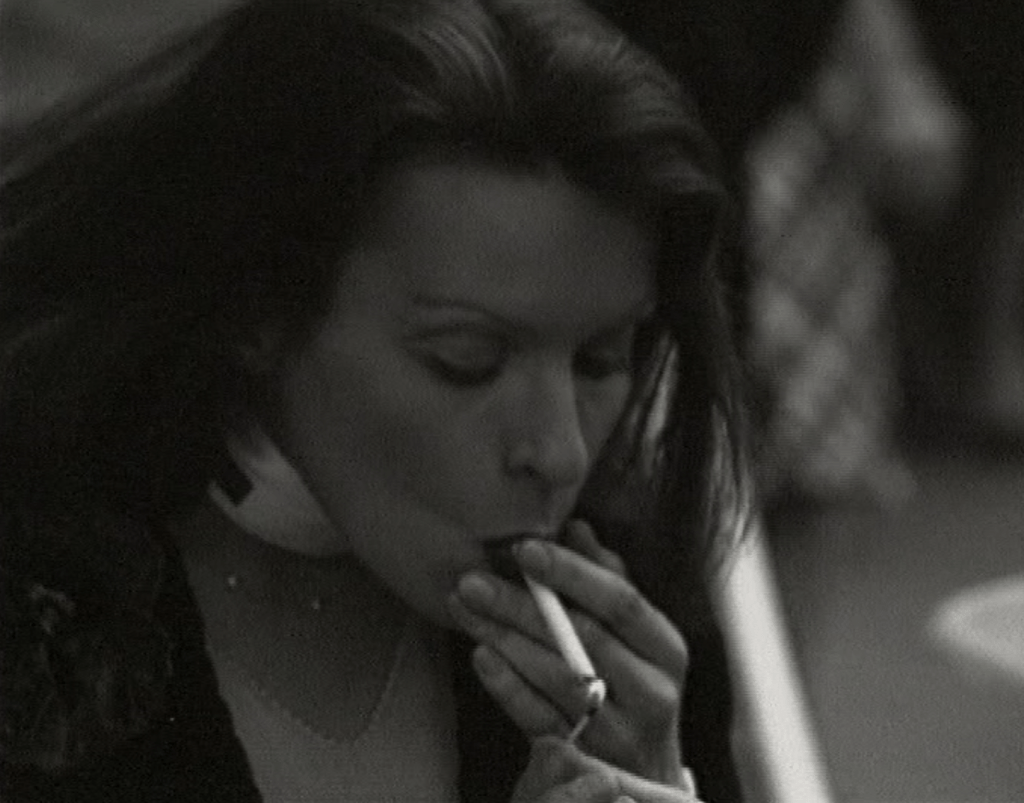

In TV-News (TV-Tod II) [TV-News (TV-Death II), 1970], a newsreader smokes inside a sealed box modeled after a television set. The smoke thickens until he chokes—television devours its own anchor. The medium is not a conduit but a coffin. Likewise, in Synthesis. Ein/Aus (Synthesis. On/Off, 1972), Weibel and a machine play a linguistic ping-pong of “On” and “Off,” each action answering the other. The logic becomes absurd, recursive; command and obedience collapse into a meaningless loop. The machine’s autonomy is unsettling, the human voice increasingly vestigial.

The infamous TV-Aquarium (TV-Tod I) (1970) turns people’s TVs into aquariums. Viewers stare into a dead device, but the death is never seen; only its eerie aftermath remains. The Endless Sandwich (1969) expands this dread by trapping Weibel inside an infinite regress of images within images, a mise-en-abyme that predicts the coming age of lost signals and feedback loops.

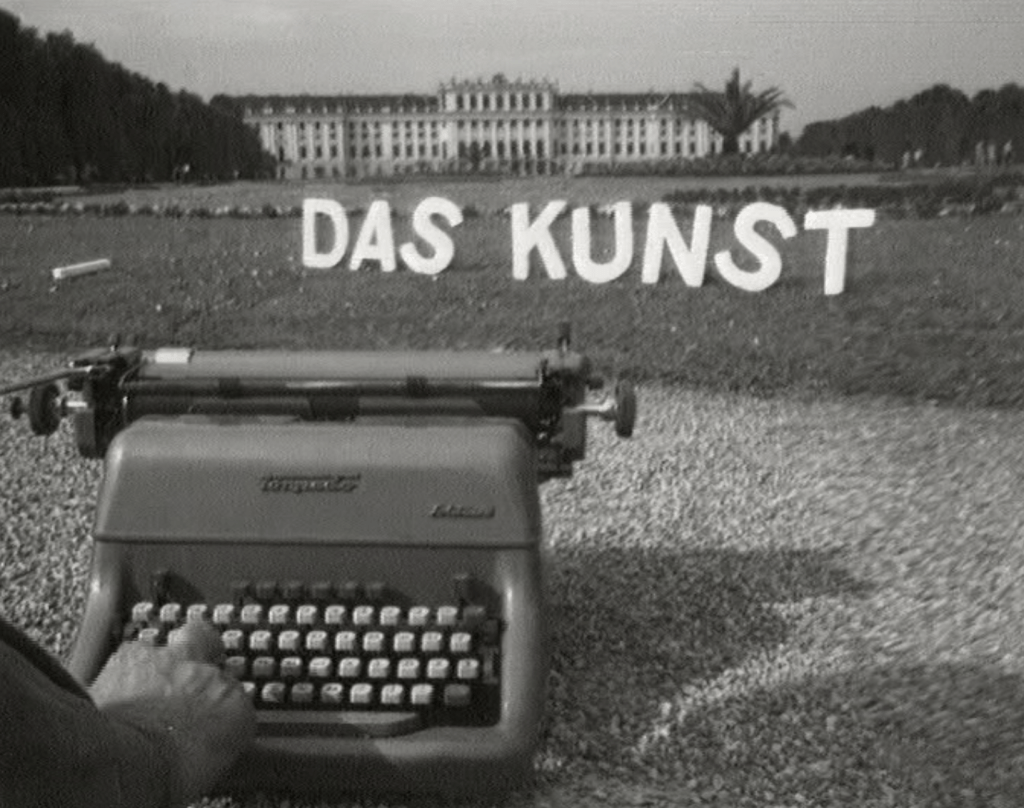

Jede Aktion löst eine andere aus (Every Action Causes Another, 1967) introduces a linguistic mischievousness. Outside Schönbrunn Palace, the phrase IST DAS KUNST (IS THAT ART) appears. As he types each letter on a typewriter, it flies away, the words disassembling the moment they are formed. Meaning is transient; the question evaporates even as we try to grasp it. Imaginäre Wasserplastik (Imaginary Water Sculpture, 1971) extends this logic to gesture: throwing water into the air, filmed from multiple angles, becomes a kind of sculpture of the ephemeral. The frozen frames, described by Weibel with pedagogical clarity, show time dismembering action.

Identity becomes the next battleground. In Switchersex (1972), two monitors overlay mismatched body parts, creating an uncanny composite that is neither male nor female but a lambent hybrid of both. No sound, only the eerie synchronization of gesture. The woman’s final smile is not reassurance but rupture: the identity we thought we could assemble slips away. Tritität (1975) overlays Weibel’s face with depictions of Christ; he makes the holy image blink, smile, and grimace, corrupting its sacred aura with mechanical animation. Selbstbegrenzung – Selbstbezeichnung – Selbstbeschreibung (Self Limitation – Self Drawing – Self Description, 1974) reveals the impossibility of depicting oneself: the drawing hand is always outside the field of representation, escaping itself. In Parenthetische Identität (Parenthetical Identity), genealogy becomes absurd. To be your own brother is a logical and emotional impossibility; the film laughs at the ways we inherit ourselves.

Monodrom (1972) is a one-way critique. A “human sculpture” is moved about by instructions called in by viewers, denting a clay wall with its collective, yet directionless, will. Hausmusik (Chamber Music, 1972) stages a dinner party where sound dictates behavior and images are ripped, drowned, and reconstituted. The domestic sphere becomes a battlefield for interference.

Zeitblut (Timeblood, 1972) may be Weibel’s darkest. As he delivers a lecture on the end of time, a glass on the table slowly fills with blood dripping from his arm. Thus, time is reconfigured as a draining of life, an irreversible seepage. Perhaps every statement about time is written in blood.

Across these works, Weibel treats television and video as volatile as gasoline yet as fragile as breath. He understands them as systems of power, of surveillance, of seduction. But he also understands them as languages that can be bent into stutters, errors, and puns. Depiction is a crime reveals a world in which images commit offenses but can also confess, malfunction, or refuse to behave. It is a body of work that feels prophetic: a rehearsal for an era in which screens would become omnipresent, insistent, invasive, and inescapably within reach.

Articolo molto interessante. Grazie.