Optical Vacuum opens into a territory that is neither fully voyeuristic nor fully clinical, yet borrows from both dynamics to unsettle the viewer’s most basic assumptions about seeing. Dariusz Kowalski poses the provocation at the heart of his project: “If surveillance really does scare society,” he asks, “why aren’t people marching in the streets?” Perhaps because these mechanisms have already seeped into our daily routines. Perhaps because their ubiquity now feels natural. Or perhaps, more troublingly, because we have forgotten how to see what they see. Situated between fascination and dread, Kowalski’s work draws its power from the way it reanimates what is usually overlooked: cameras that watch without intention, spaces in which nothing happens yet everything remains visible, the dull hum of existence captured with no expectation of an audience. His images vibrate with a tension that belongs neither to narrative cinema nor documentary reportage but to the uncanny region between them, where meaning thins to near-invisibility. This atmosphere is sharpened by the spare, icy electronic music of Stefan Németh, which lends each frame a crystalline edge.

Optical Vacuum (2008) clarifies the Kowalskian aesthetic with particular force. For 55 hypnotic minutes, alongside the disembodied voice of American artist Stephen Matthewson—recorded on a Dictaphone and recounting fragments of a life that never reveal their anchor—we watch images extracted entirely from internet camera feeds. Crucially, the words and images never intersect; they pass one another like strangers in a narrow corridor. The diary traces the outline of a subject without a body, while the surveillance footage supplies bodies emptied of subjectivity. The viewer drifts between attachment and estrangement, moving from a mahjong table to a radio station control room, from a Japanese laundromat to Alaskan icefields, from snippets of pedestrian routine to desolate rooms thickened by absence. The most disturbing footage is not that of human activity but of empty spaces: rooms whose only occupant is the camera itself, regarding the void with mechanical patience. Each feed is a miniature cosmos that never asked to be witnessed. Kowalski reveals the macro hidden in the micro, the metaphysical weight of absence, the enormity of unhappening. The effect recalls the vast, impersonal atmospheres of ambient musician Thomas Köner yet remains grounded in the banal infrastructure of online surveillance.

Elements (2005) functions as a companion, turning toward the frozen expanses of Alaska through webcams of the Alaska Weather Camera Program. Intended to track climatic conditions at airfields and remote outposts, these feeds become landscape cinema once reframed by Kowalski. They are, as Marc Ries notes, “horizon films rather than object films,” concerned less with discrete entities than with thresholds, with the way space dissolves at its perimeter. Time-lapse and mechanization erode immediacy, transforming clouds and light into drifting stains on low-resolution surfaces. Snowfields take on painterly abstraction. The smallest shift in illumination feels catastrophic, as if some distant rupture were passing through. Human presence is reduced to traces: tire marks fading into whiteness, a runway half-consumed by drifting snow, a horizon line trembling in ambient pressure.

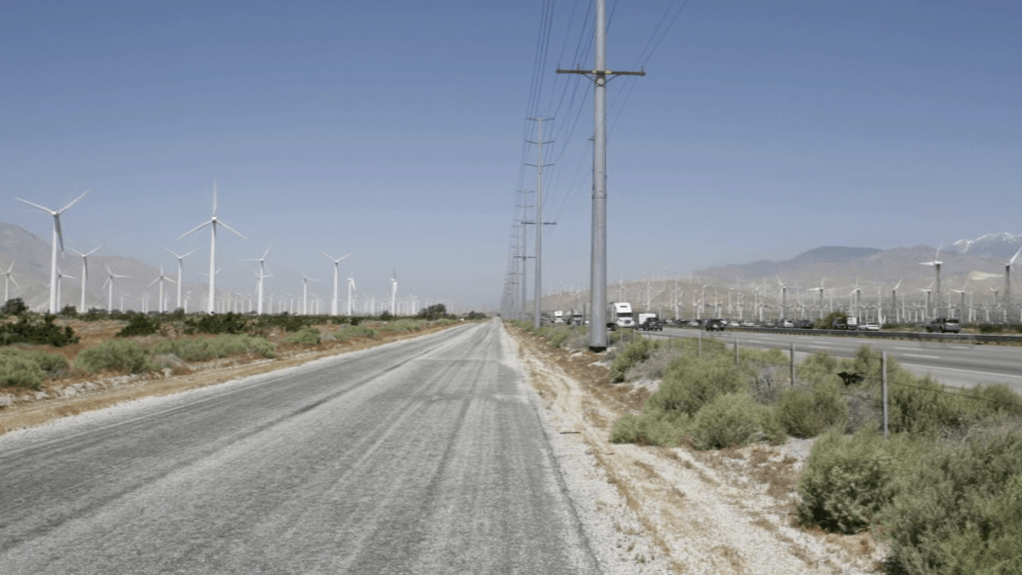

Luukkaankangas – updated, revisited (2004) shifts its attention to Finland via the webcams of the Finnish Road Administration. Remote roads, blanketed in snow and rarely interrupted by headlights, evoke a world moving without witnesses. Wind skimming across asphalt becomes a form of drawing. The roads seem to register the presence of travelers who never appear. It is as if an unseen hand were composing messages that dissolve before they can be understood.

The bonus films take us further inward. Ortem (2004), an arresting work in its own right, descends into the Viennese metro system. Tunnels, stairways, elevators, and security feeds compose a subterranean organism, something cellular and pulsing beneath the city’s surface. Distorted loops create circuits of motion and memory. At times, the tunnels blank out into a red screen, as if the system itself were undergoing a convulsion. The film ends with trains sliding past in opposing directions and a static wall, a return to the network’s resting heartbeat.

Interstate (2006), composed from thousands of still photographs, provides a final act of distillation. Real-time traffic sounds persist, but the images freeze: rest stops, windmills, gas stations, vehicles suspended in mid-transit. Time advances while the frames remain inert. The effect is spectral, a country glimpsed only in that state between motion and stasis. The highway becomes a long exhalation of images that never congeal into movement, a road movie where the road never bends.

Together, these works propose a distinct way of seeing. Kowalski offers a cinema rooted not in events but in the conditions that allow events to be seen. He gives us a world composed of glances without biological gazes. And in doing so, he raises a disquieting possibility: that surveillance is not terrifying because it watches us but because it reveals how much of the world continues without us, indifferent to whether anyone bears witness or turns away.