My latest review for All About Jazz is of the Alex Merritt Quartet’s superb CD debut, Anatta. Click the cover below to read and listen.

Author: Tyran Grillo

Food: This is not a miracle (ECM 2417)

Thomas Strønen drums, electronics, percussion, moog, fender rhodes

Iain Ballamy saxophones, electronics

with

Christian Fennesz guitar, electronics

Recorded June 2013 at Holand Sound, Oslo

Recording producer: Thomas Striven

Engineer: Ulf Holland

Mixed February 2015 at Holand Sound, Oslo by Ulf Holand, Manfred Eicher, and Thomas Striven

Mastered at MSM Studio, Munich by Christoph Stickel and Manfred Eicher

An ECM Production

U.S. release date: November 20, 2015

For its third ECM course, the duo of Thomas Strønen (drums, electronics, percussion, Moog, Fender Rhodes) and Iaian Ballamy (saxophones, electronics), known together as Food, serves up its most introspective chunk of nourishment yet. With assistance from Christian Fennesz (guitar, electronics), who last guested on Mercurial Balm, the project burrows even deeper into its lyrical universe with atmospheric phasers set to stun.

Under the creative disclosure of This is not a miracle, Strønen has taken to crafting every piece using elements culled from hours of studio improvisation with the musicians and producer Ulf Holand, whose hand was so gorgeously evident in Nils Petter Molvær’s Khmer. Strønen admits to starting more often with a structural rather than melodic idea before cutting the music, in his words, “to the bone.” Cutting is precisely the word, as linear utterances became spliced, looped, and restructured into fully fledged, standalone grooves.

It would be tempting, once the distorted guitar and muffled bass beats of “First Sorrow” pulse their way into the mind’s ear, to place the origins of this music at a far remove from Earth, when really it is torn from the book of an internal cosmos. Brushed with fire and written in ashes, its pages glow with the allure of a sere orthography in “Where Dry Desert Ends,” making even this unforgiving territory feel like cashmere on winter skin. Drums add their skipping traction to the dunes, while synthesizer and saxophone cut the sky with their cloudless scissors. A marked shift in viewpoint flushes heat as if through an emotional exhaust system of continental proportions, turning the emptiness of sunset inside out as a gift for the coming dawn.

Much of what awakens thereafter draws its nutrients from somewhere between this planet’s surface and its core, a comfort zone of difference and sculpted time. Whether whirling in the title track’s dervish circles or overlapping reeds in “Death Of Niger,” crunching through the detritus of “Sinking Gardens Of Babylon” or drifting over “The Concept Of Density,” just high enough to traverse the highest mountains yet low enough to ingest the detail of every village below, genetics bleed through every joining of head and tail with the power of unifying color.

Whatever the means at hand, lineage remains at the forefront of Strønen’s sound-world. Khmer kinship is strongest in “Exposed To Frost,” of which Fennesz’s biwa-like twangs imply another world within, while the drumming of “Earthly Carriage” and “Without The Laws” has the tuneful attention of label mate Manu Katché. His simple guidance is as shifting as the sand of an hourglass, pulling notes by gravity into mountainous ends. Similarly, “The Grain Mill” seeks the chicken in the egg. This glitch-laden lullaby enables a searing emergence from Fennesz, who tears through the veil of dreams into waking reality, where coronas whip themselves in place of lovers drowning in self-regard.

Whatever poetry This is not a miracle might inspire, it is, as the title implies, a practically molded object. The band has since taken these constructions as cohesive compositions, performing them as such in live concerts. But their democratic foundation remains audibly intact, and is perhaps the greatest force keeping them from being sucked into the black hole of countless other albums vying for your attention. This one tugs as the moon does the ocean, leaving shores refreshed and glistening beneath its light.

(To hear samples of This is not a miracle, please click here.)

Dino Saluzzi & Anja Lechner: El Encuentro (ECM 5051)

Dino Saluzzi

Anja Lechner

El Encuentro: A film for bandoneon and violoncello

Directors: Norbert Wiedmer and Enrique Ros

Camera: Norbert Wiedmer and Peter Guyer

Editing: Katharina Bhend

Sound, sound editing, and sound mix: Balthasar Jucker

Production: PS Film, Biograph Film

Co-produced by SRF

Post-production: Recycled TV

In Sounds and Silence, Norbert Wiedmer produced a rather fleeting portrait of ECM Records and its head Manfred Eicher, leaving viewers with, at best, vague sketches by trying to do too much in one go. But with El Encuentro, glimpses of which one might remember seeing in the former documentary, he has given us the film that should have been. Along with co-director Enrique Ros, Wiedmer touches more of the label’s ethos by following only two of its major artists than Sounds and Silence does in profiling many more besides. Despite being from opposite sides of the Atlantic, gentle giant of the bandoneón Dino Saluzzi and cellist Anja Lechner have bridged waters of their own making since 1998, when they first collaborated in the Kultrum project that featured the Rosamunde Quartett, of which the cellist was founder.

What makes El Enceuntro such an insightful window is the relative clarity of its narrative glass. At its core is a trip taken by Dino and Anja—so one feels compelled to call them after getting to know them so well by the end credits—to Salta, Argentina, where the bandoneonista absorbed the tango that would become central to his life. It’s an art form that would become increasingly important for Anja, who cites her own deep knowledge of, and respect, for the tango as a motivation for forging this intergenerational partnership with Dino. She recalls learning these rhythms for the first time in Argentina, where signatures rendered cut and dry through classical training now blossomed at her fingertips, reinvigorated.

Dino meanwhile looks back on memories of his father, who after working a long day at the factory would sing for their village. Dino took to his father’s love of song like a sunset to ocean and, as the film makes clear, has passed that spirit on to Anja in kind. Indeed, the cellist says that even though Dino is always more comfortable playing with his family, she feels she has become a part of it. Whether dancing with the locals or navigating a recording session with Dino and his brother Felix, she adapts with chameleonic precision—which is to say: unthinkingly.

But Dino’s story is as much about leaving home as finding it. He regales us with stories of putting his home country behind him to support his family, and of finding an unexpected brother in the late George Gruntz, who in 1982, as president of the Berlin Jazz Festival, traveled to Latin America in search of musicians and recruited Dino on the spot. No one in Gruntz’s band had ever seen or heard a bandoneón before, and this opportunity would prove career-defining.

The past, however, is never too far behind. As Dino admits, “I compose with memories and hopes,” and in so doing kneads the passage of time into desired shapes. In this respect, the film is as much a meeting of lives as of minds. Anja lets us in on her own past: playing with rock bands at age 12, among whom she learned to improvise in the heat of the moment; hearing Dino’s music for the first time in Munich, where she’d so dutifully immersed herself in classical music of the European masters, even while surrounding herself with the melodies and forms of other places. And for her that’s the key. You have to go to these places to experience the emotional core of their music. Location is vocation. It’s something that cannot be substituted or recreated.

None of this is meant to suggest that Lechner has abandoned her classical foundations. Far from it, as evidenced in her interactions with composer Tigran Mansurian in Armenia, the country dearest to her after Argentina.

The cameras are there again for conversations with Levon Eskenian, who explains to her the sacred music of Armenia, and how when playing folksongs on the duduk one must always convey a sense of improvisation. Anja thus characterizes life in Armenia as more immediate, whereas in Argentina people truly engage and look into you. Such is the balance of her traveling life.

On Dino’s own travels, no companion has been more constant than his trusted bandoneón. “I can’t conceive of life without the bandoneón,” he says. “The instrument has spoken with modesty since its conception. It doesn’t raise its voice, it only speaks with calmness, simplicity, and directness. All of the words are written here. All of the thoughts are here. All of the difficult equations are here. You only have to serve to bandoneón and understand that you’re letting the human experience pass through other channels.” But he also believes that bandoneonists should explore beyond the tango and create new forms of music. As if his recordings weren’t already ample proof of this advice in action, excerpts from concerts with drummer U.T. Gandhi and singer Alessandra Franco, and with the Metropole Orchestra in Amsterdam’s Musiekgebouw under the baton of Jules Buckley, show just how catalytic the instrument can be.

But it is in combination with the cello where channels of communication open their hearts to the vastest possibilities. Just as Anja says, “Music is a world in which all emotions exist,” so are emotions a world in which all music exists. And at their center, we can feel these two souls creating a third for the listener to inhabit at will.

Early on in the film, Dino wonders how people can connect at all to his melancholic music, even as he recognizes something that meets the listener halfway. “For me,” he goes on, “doubt is driving force. It’s like gasoline. You use gasoline to run a car. And for us to work, we need doubt. Because if doubt is a driving force, then it can’t become a paralyzing problem. On the contrary, it’s a generator of ideas and desires, of searches and answers to the great questions we have.” And if we must be the electricity that powers this generator, how fortunate we are to be swept up in its current.

Keith Jarrett Trio: Live In Japan 93/96 (ECM 5504/05)

Keith Jarrett Trio

Live In Japan 93/96

Keith Jarrett piano

Gary Peacock bass

Jack DeJohnette drums

DVD 1

Recorded live in Tokyo, July 25, 1993 at Open Theater East

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded by Toshio Yamanaka

Produced by Yasuhiko Sato

Executive producers: Hisao Ebine and Toshinari Koinuma

DVD 2

Recorded live in Tokyo, March 30, 1996 at Hitomi Memorial Hall

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded by Toshio Yamanaka

Produced by Yasuhiko Sato

Executive producers: Hisao Ebine and Toshinari Koinuma

Concerts produced by Koinuma Music

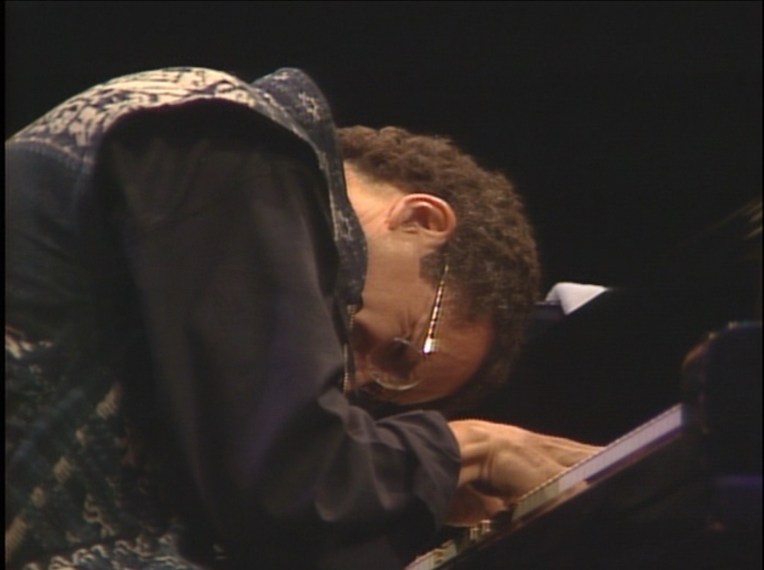

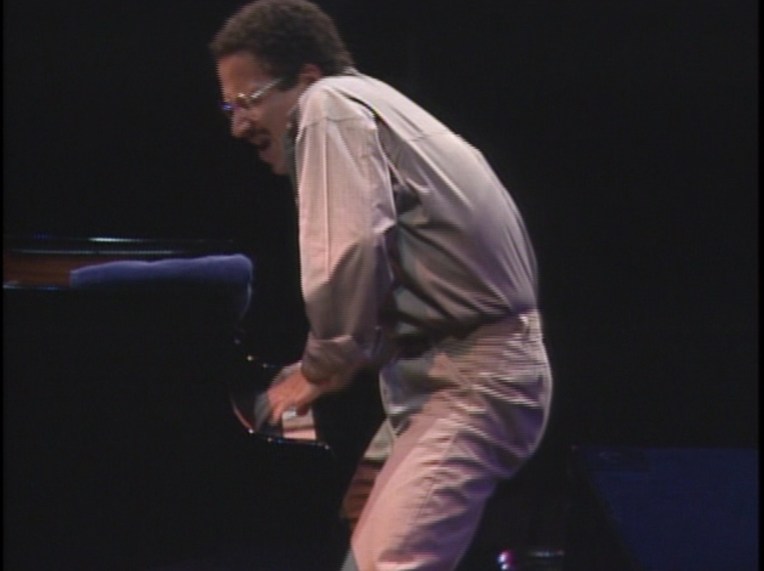

It’s one thing to hear, but quite another to see, the Keith Jarrett Trio in action. For those unable to do so in a live setting, this two-DVD release is the next best thing. Like the Standards I/II set that precedes it, this one was recorded in Tokyo, but puts about a decade between those first Japan performances.

A 1993 gig at Open Theater East takes place in the heart of a sweltering summer. The air shines both with the music and with the rain that forces a large and dedicated audience to listen from beneath ponchos, and the musicians to play from beneath a clear canopy. The video quality is much finer this time around, and despite a rocky start born of technical issues and the weather, captures one of the trio’s finest sets available on any medium.

What separates this concert from the others available on DVD is the openness of the band’s aura. Jarrett more than ever plays for his appreciative listeners because he understands the bond into which nature has pushed them. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Jarrett’s The Köln Concert also famously began in the least ideal of conditions. Clearly, the pressure set him on an unprecedented creative path. And so, even as the trio struggles to feel out the climate in Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way” (throughout which Jarrett must often wipe down the keyboard with a towel), all while latecomers snake to their seats, we can feel the groove emerging one muscle at a time. After the worldly touches of “Butch And Butch” and “Basin Street Blues,” we know that things have been set right.

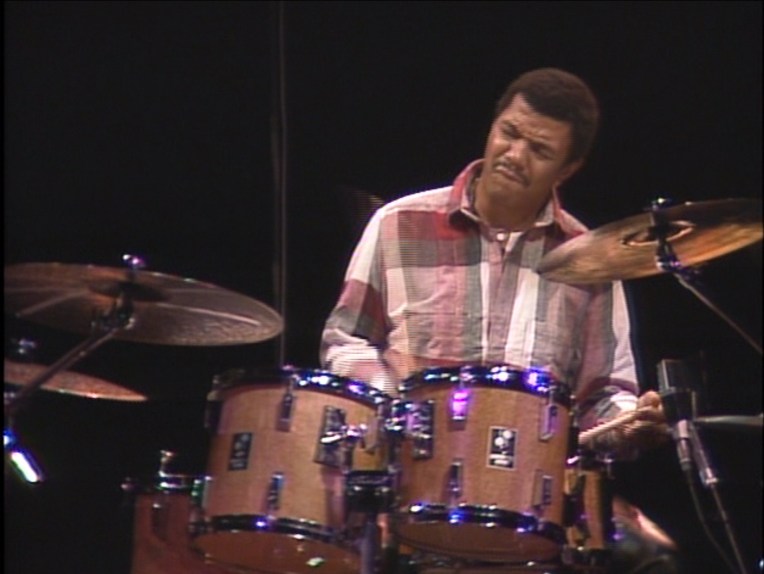

Whereas in the previous Japan documents Peacock proved himself the man of the hour (although, to be sure, the breadth of his architectures in “If I Were A Bell” and “I Fall In Love Too Easily” are as masterful as they come), it’s DeJohnette who produces the deepest hues of this rainbow. His sticks make evergreens like Sonny Rollins’s “Oleo” that much greener, and turn a 26-minute rendition of Miles Davis’s “Solar,” combined with Jarrett’s “Extension,” into a downright sacred space.

As with the 1986 concert on Standards I/II, the trio ends on three encores: “Bye Bye Blackbird,” Jarrett’s “The Cure,” and “I Thought About You.” In all of this one can sense a quiet storm of commitment to the music that flows from within. Melodies breathe, reborn, requiring open hearts to know their graces.

The year 1996 brings us to Hitomi Memorial Hall, where Jarrett and friends jump fully refreshed into “It Could Happen To You.” As always, Jarrett’s lyrical intro reveals little about the mosaics soon to follow. He takes the theme and its surrounding chords as a starting point down densely textured corridors. Which is, of course, what improvisation is all about: dungeon crawling without a map yet knowing that a destination will wrap its arms around you eventually. Jarrett seems to unravel every possible path into its fullest and on through the ballad “Never Let Me Go,” in which the pianist transcends the status of storyteller to that of myth keeper.

“Billie’s Bounce” is a staple not only for its composer, Charlie Parker, but also for Jarrett. As one of his prime expressive spaces, it layers all the bread and butter that make his art so nourishing. But we mustn’t forget that each member of this unit is equally important. In “Summer Night,” Peacock’s gentility is Jarrett’s flame, shining like the moon with a song to sing, and DeJohnette’s opening to “I’ll Remember April” shows a drummer with just as much to say from the bedrock, even as Jarrett evolves in real time through every change in the rapids above.

Other standbys such as “Mona Lisa” and crowd favorite “Autumn Leaves” open as many new avenues as they retread. With a crispness of feeling, Jarrett grabs the spotlight, while lively soloing from Peacock and fancy brushwork from DeJohnette make the picture whole. Even the familiar strains of “Last Night When We Were Young” become something new when they melt into Jarrett’s groovier “Carribean Sky.” It’s what one can always count on with this trio: playing as if for the first time.

The Bud Powell tune “John’s Abbey” commands from the sidelines as Peacock and DeJohnette go from canter to gallop and sets off a rapid-fire succession of closing tunes. A touching rendition of “My Funny Valentine” falls like a tear of quiet joy into Jarrett’s “Song,” in which the musicians open a book you always meant, and at last have the chance, to read again. “All The Things You Are” and Ray Bryant’s lesser-heard “Tonk” end the set with a satiating balance of delights. Nothing added, nothing taken away.

Keith Jarrett Trio: Standards I/II – Tokyo (ECM 5502/03)

Keith Jarrett Trio

Standards I/II – Tokyo

Keith Jarrett piano

Gary Peacock bass

Jack DeJohnette drums

DVD 1

Recorded live in Tokyo, February 15, 1985 at Koseinenkin Hall

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded and mixed by Toshio Yamanaka

Production coordinator: Toshinari Koinuma

Produced by Masafumi Yamamoto

Executive producer: Hisao Ebine

DVD 2

Recorded live in Tokyo, October 26, 1986 at Hitomi Memorial Hall

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded and mixed by Seigen Ono

Production coordinator: Toshinari Koinuma

Produced by Masafumi Yamamoto

Executive producer: Hisao Ebine

Concerts produced by Koinuma Music

Standards I/II is an invaluable two-DVD archive of the Keith Jarrett Trio’s inaugural tours of Japan. The first, recorded at Tokyo’s Koseinenkin Hall on 15 February 1985, offers the pianist at his heartfelt best in an intro as tender as a drizzling rain. So begins a smooth version of “I Wish I Knew,” through the lens of which bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette illuminate the spectrum of this format like few others can. What distinguishes them, as made clear in this concert opener, is their consistent ability to surprise. Sure, the technical prowess required to carry off such florid versions of “If I Should Lose You” and “It’s Easy To Remember” is formidable to say the least, but how much more virtuosity there is to be savored in the ballads. The night-laden memories of “Late Lament” add softness to the set list’s emerging palette, even as they whisper in a language as crystalline as all the rest. This is a diamond in which every occlusion represents an opportunity for clarity. “Stella By Starlight” starts with Peacock and Jarrett emoting in space and time without allegiance to either, working into a 14-minute groove so sublime that it melts.

To be sure, the more upbeat tunes have a crispness all their own. “If I Should Lose You” finds Jarrett listening intently to his bandmates, who exchange tactile glances in anticipation of DeJohnette’s rolling play. But whether the drummer is riding the rails in “It’s Easy To Remember” or adding choice accents to a diagonal “God Bless The Child,” he leaves plenty of room for his audience to grow in kind.

Jarrett originals such as “Rider” and “Prism” showcase his penchant for gospel and Byzantine grooves. In these tunes the band reaches a high point of synchronicity, working a detail-oriented art into a genre all its own. Even the lighter “So Tender” retains full emotional accuracy, going all in via Peacock’s supernal melodizing. All of which leads to sixteen and a half minutes of soulful unpacking in “Delaunay’s Dilemma.” Peacock fascinates again in his soloing toward the finish line, while DeJohnette sings even as he punches his way toward bluesy victory.

The second Japan concert was recorded at Hitomi Memorial Hall, also in Tokyo, on 26 October 1986. This standards extravaganza is the regression to the previous concert’s progression, but loses no sense of integrity for its introversion. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” eases into things with sweeping finesse such as only Jarrett can pull off. It is followed by “With A Song In My Heart,” the meditation of which morphs into some solid invigorations. Peacock and DeJohnette share a flawless rapport, the drummer popping off that snare like a machine gun.

So begins an alternating pattern of valleys and peaks, which by the end leave behind an even more cohesive program than the first. We next dip down into a tune the trio plays like no one else: “When You Wish Upon A Star.” Jarrett’s rendering makes even the most familiar blossom anew with emotional honesty. The mastery on display in this quintessential example is as pliant as Peacock’s strings, and carries over into the interlocking tempi of “All Of You.” For this, the bassist leaps forward with the first of two solos, moving from robust to filigreed without loss of syncopation.

The bassist turns out to be the sun of this solar system, lathering a mysterious yet lucid “Georgia On My Mind” and a duly nostalgic “When I Fall In Love” with enough light to spare in conversation with his bandmates. DeJohnette, for his part, airbrushes the night sky in “Blame It On My Youth” and lets the groove be known behind “Love Letters.” And in tandem with Jarrett, he feeds magic into the masterstroke of “You And The Night And The Music.” Unforgettable.

Each of the three encores—“On Green Dolphin Street,” “Woody ’n You,” and “Young And Foolish”—is a virtuosic gem set to twinkling and reminds us that Jarrett and his associates came this far only by selecting their divergences lovingly.

Feldman/Satie/Cage: Rothko Chapel (ECM New Series 2378)

Morton Feldman/Erik Satie/John Cage

Rothko Chapel

Kim Kashkashian viola

Sarah Rothenberg piano, celeste

Steven Schick percussion

Houston Chamber Choir

Robert Simpson conductor

Cage and Satie recorded May 2012 at Stude Hall, Rice University in Houston

Feldman recorded February 2013 at The Brown Foundation Performing Arts Theater, Asia Society Texas Center

Programme: Sarah Rothenberg

Tonmeister: Judith Sherman

Engineer: Andrew Bradley

Editing assistant: Jeanne Velonis

Mastered at MSM Studio, Munich by Judith Sherman and Christoph Stickel

Produced by Judith Sherman

An ECM Production

U.S. release date: October 23, 2015

To encounter a painting of Mark Rothko (1903-1970) is to stand not before but within it. The more one gazes, the more blended one becomes into its borderless horizons. This dynamic is duly obvious in Rothko Chapel, a nondenominational space hung with his canvases and where visitors, observes pianist Sarah Rothenberg, “actually inhabit the paintings from the inside.” After the chapel’s posthumous opening, composer Morton Feldman (1926-1987) was asked by philanthropists Dominique and John de Menil to pen a tribute, and thus the centerpiece to Rothenberg’s carefully assembled program was born.

Said program was originally presented by Houston-based Da Camera, an organization that Rothenberg has lead since 1994, and under the auspices of which she presented a 40th Anniversary Concert at Rothko Chapel in 2011. Translating the energies of this event into a studio experience transcends the qualities of a reproduction, for the musicians’ raw talents move so organically as to yield an original work of art with immersive qualities all its own.

From the rumbling timpani that opens Rothko Chapel alone, one already knows that the composer must have been both admirer of, and friend to, the artist. That he was, and their penchant for debate and banter codes its way into every click of aperture as the nearly 30-minute piece unfolds. Then again, it might be more accurate to say that Feldman’s masterwork “infolds,” for like a thought compressed into pigment, it colors the mind with simple yet deeply planar contrasts. Other percussive elements shine as the underside to a viola’s burnished top. These two might seem oppositional, were it not for Kim Kashkashian, in whose rooted bowing one may hear the spirit of hues and forms that put Feldman’s cells in an inner tandem not unlike that of the Rothkos themselves. The presence of choir, then, surely manifests the darkness into which Rothko’s angles seem to forever recede. Feldman’s sounds are thus every bit as painterly as Rothko’s applications were sonic. Each follows its own frequency toward a common endpoint—which is to say, a point without end. Individual voices, bowed and throated alike, constitute not “solos” but single bands of fuller spectra. As Rothenberg details in her beautiful liner notes, Feldman recognized the logical impossibility of expressing stasis in music, even if one may feel an illusion of it, for as the choir ends in mid-impulse, leaving us suspended in the void of those permeating rectangles, it is all we can do to inhale the illusion before it leaves us.

In this context, the soundings of Erik Satie (1866-1925) and John Cage (1912-1992) are drops in an ever-expanding pond. Satie was a focal point of Cage’s contemplative life, and much like Rothko to Feldman served to enhance a diffuse and intimate science. Satie’s obsession with time, as Cage saw it, surely helped both composers to recognize the value of space. Cage’s Four2 (1990) and Five (1988), both for choir, train the ear on a different field of overlaps. The bleed-through of these voices is that of watercolor, touching the paper’s edge as if it were a new beginning all the same. Higher voices ring out with the announcement of a barely-risen sun, soaking the clouds with generative power and carrying over denominators of motivic cells until they are stretched beyond recognition. The multiplicity of singers yields a selfless quality, which finds fullest expression in ear for EAR (Antiphonies). This 1983 piece for choir and tenor soloist transmits wordless impulses into a meditation on emptiness.

The latter, in being framed by the first two of Satie’s four Ogives for piano, seems even more an exercise in balance: between flat and sharp, loud and quiet, inner and outer. Nos. 1, 3, and 4 of Satie’s Gnossiennes similarly daub the program, each spread until it touches another. Their appearance is all the more vivid for their gentle persuasions, touches of the wrist leading us down a path that crumbles behind us as we tread. Rothenberg’s approach to the keyboard assures that these famous pieces feel familiar on their own terms.

It has been fascinating to watch Cage’s 1948 In a landscape evolve through the New Series. This is its third appearance on ECM’s classical imprint, marking programs by Herbert Henck and Alexei Lubimov. Ending an album as it does here, it feels all the more natal. Its arpeggios are as profound as the C-major prelude of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and here absorb the resonance of that canonical past with hints of an unknown future.

These composers, and the artists from whom they gathered inspiration, may have been the avant-garde, but in them was also something far older, as primal as it was primary, that spoke to creation as the lotus of ego and its sonorous destruction.

(To hear samples of Rothko Chapel, please click here.)

The Good Guy Always Wins: Behind the Mystery of the Daniel Bennett Group

On Clockhead Goes to Camp, multi-instrumentalist and composer Daniel Bennett took listeners on a storybook journey. But if that 2013 album was a Spirograph drawing, this 2015 follow-up is a Spin Art extravaganza. The Mystery at Clown Castle brings to fruition a reimagined lineup, situating the bandleader (who capably switches between alto saxophone, flute, piccolo, oboe, clarinet, and piano) among the fresh aliliance of guitarist Nat Janoff, bassist Eddy Khaimovich, and drummer Matthew Feick.

The present cast of characters is no less eclectic than the former, and guides the project along fruitful avenues of ingenuity. The roster change, as made clear in an e-mail interview, is in no way the result of creative differences, but instead born of the need for a touring band. “I never burn bridges,” Bennett assures. “My musicians are like family to me.” Bennett in fact continues to work with his Clockhead musicians on a regular basis, but has taken to test-driving newer associates through his monthly residency at Tomi Jazz in midtown Manhattan. The vibes honed on Tomi’s stage pay their dividends in the studio, where the band’s unities, but also its lively fragmentations, acquire full expressive reign.

Although Mystery feels like a continuation or companion of Clockhead, it’s also very much its own animal—or should I say animals, because the set list is populated with them. “Paul Platypus” is the first of an evocative menagerie and finds the band firing on all cylinders. It’s also a mighty fine vehicle for Khaimovich, who Bennett calls “one of the busiest bass players in New York City” and who encouraged the bandleader to make use of electric bass for the first time. The instrument adds tactile shading here (and subtlety to the nocturnal carnivalesque that is “The Spinning Top Stood Still”), while fleshing out the lower spectrum beyond Janoff’s six singing strings.

The flute-led “Nine Piglets” is reprised from its last appearance on Clockhead in a fully reinvigorated arrangement. This radio-friendly tune, one of the band’s most requested, discloses Bennett’s overtly pop influences, which peek their heads above water on “Strange Jim And The Zebra” and “Uncle Muskrat.” The latter boasts the talents of pianist Jason Yeager, a prolific sideman whose backyard jam session chops lend further delights to two freely improvised tracks.

The album’s nonhuman considerations come at us like a stampede in the spoken poetry of Britt Melewski, who in “Morning” shouts, “What animal are you?” It’s a profound, if tongue-in-cheek, question to consider in such a whimsical musical universe, the answer to which can only be articulated in melodies without words. Such contrasts take to higher altitudes in his creepily auto-tuned “Minor Leaguer,” beneath which oboe and guitar lay down a beautiful stage.

Opener “The Clown Chemist” is duly representative of Bennett’s style. Technically proficient yet full of sparkle and personality, its circularity opens the way for creative ornamentation. As throughout the album, the melody is primary, as attested by the fact that Bennett composes first at the guitar, as one would a song, before transferring to his lead of choice. Mystery is likewise recorded like an indie band. Producer MP Kuo does little to mask the band’s live sound, which breathes through tracks like “Flow” with cinematic clarity. When I asked Bennett about his nonmusical influences, his response was as multifarious as his music:

“You’re going to laugh, but I really love formulaic television shows from the 1980s. I love the ‘good guy vs. bad guy’ plots. And the good guy always wins. That’s the way it should be! There’s too much cynicism in this world. So I do it my way. I don’t follow jazz trends and I don’t push any political agenda with my music. I just want to make people feel good. I am on this earth to be a servant to others. A wise man once told me, ‘Worship God and serve the people.’”

It’s a fine philosophy to follow for a group just voted “Best New Jazz Group” in 2015 by Hot House Jazz Guide and, with another album already recorded, these cats are on their way to making the future of jazz that much brighter.

For more information, check out their official site here.

Enrico Rava Quartet w/Gianluca Petrella: Wild Dance (ECM 2456)

Enrico Rava Quartet

w/Gianluca Petrella

Wild Dance

Enrico Rava trumpet

Francesco Diodati guitar

Gabriele Evangelista double bass

Enrico Morello drums

with

Gianluca Petrella trombone

Recorded January 2015, Artesuono Recording Studios, Udine

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Produced by Manfred Eicher

U.S. release date: August 28, 2015

Wild Dance documents yet another chapter in the career of Italian master trumpeter Enrico Rava, who for this outing has assembled one of his most exciting bands to date. Along with guitarist Francesco Diodati, bassist Gabriele Evangelista, and drummer Enrico Morello, he welcomes back into the fold trombonist Gianluca Petrella, whose darker brass has added memorable contrast to Rava’s quintet albums over the past 13 years. Just as many Rava originals, both new and old, populate the set list of this latest ECM collaboration, with a collective improvisation added in for good measure. The latter format, which falls penultimate in the set list, is a good litmus test for any jazz outfit, and in this respect the band succeeds beautifully. Overlapping just enough to yield thematic intimations while allowing each instrument to speak personal truth, it journeys with optimism on its sun-faded sleeve.

All of which makes “Diva” all the more alluring for noir-ish saunter. In keeping with that atmosphere, the band caresses every flutter of Rava’s hardboiled romanticism with austerity. Diodati and Evangelista are this opener’s heart and soul, stretching and tensing by turns as Rava walks the alleyways in search of connections. “Space Girl” continues the thread with similarly half-lit cinematography, by means of which Morello discloses the underlying bonfire of physiological activity required to pull this music off with such smoothness of intuition.

Enrico Rava with producer Manfred Eicher (photo by Luca D’Agostino)

“Don’t” radically changes the album’s exposure, moving with that same swagger but opening up the aperture through Petrella’s delayed entrance. In his hands, the trombone becomes a fully vocal entity that is equal parts storyteller and troubadour. His notecraft bespeaks an itinerancy that never fears the unknown. Whether winding around Rava’s core melody at the end of this tune or jumping headfirst into the animations of the next (“Infant”), he plays with fire as a house cat might a mouse—batting it around just enough to stun without the need for a kill. Such restraint is required of all the musicians under the bandleader’s employ, for even at their most unleashed (as in the up-tempo gems “Cornette” and “Happy Shades”) they make sure to keep a sizable portion of their unity within frame. Further contributions from Petrella are studies in contrast, adding humor to “Not Funny,” liquidity to the title track, and bite to the otherwise smooth “Monkitos.”

Enigma is the name of the game in “F. Express,” which by electronic whispers opens a dialogue of swinging proportions. This also happens to be one of its composer’s finest throwbacks to hit the digital shelves in some time, and is an album highlight—not only for its atmospheric acuity, but also for the archaeological care with which it is unearthed. A lone bass introduces “Sola” at length before the core-tet fleshes its skeleton with dreamlike locomotion. As if talking in his sleep, Rava spills inner secrets with the offhandedness of a sigh. “Overboard,” for its part, recalls the album’s moodier beginnings and finds the band gliding over shifting waters. In tandem with the unmistakable trumpeting, Diodati surprises with a gritty solo that stands out in an album of many standouts.

All of this and more abounds in “Frogs,” which showcases the band’s vibrancy to its fullest. Every instrument sings in this roving gallery of impulses and rhythm changes, making for a fitting closer to one of Rava’s finest.

(To hear samples of Wild Dance, please click here.)

Dino Saluzzi: Imágenes – Music for piano (ECM New Series 2379)

Dino Saluzzi

Imágenes: Music for piano

Horacio Lavandera piano

Recorded October 2013 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

U.S. Release Date: September 25, 2015

For a musician whose heart pulls so much blood from the tango and folklores both longstanding and personal, bandoneón master Dino Saluzzi is a composer in the same way that a poet is a writer. Every syllable takes on note value, which in the grander scheme of a finished piece yields shape and color. Whereas through his standby instrument he actualizes breath by way of a smaller “keyboard,” here Saluzzi bows to the interpretation of young Argentine pianist Horacio Lavandera at a much larger one in a sonic Decalogue of epic intimacy. The piano’s classical associations do nothing to obscure Saluzzi’s idiosyncrasies, which in this context mix two parts atmospheric to each melodic.

In his German-only liner notes, Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich characterizes Saluzzi’s piano music as speaking in “fragmented images.” From the rolling arpeggios that begin the 2001 title composition, we encounter a sound world that surely privileges fragments: of memory, of place, and of time. The proximity allowed by ECM’s longtime engineering ally Jan Erik Kongshaug assures listeners that the music is speaking not only to, but also into, them. Here is where the darkest hours of Saluzzi’s timekeeping are to be discovered, where every sweep of the minute hand is the arm of a shadow piecing together in slow desperation a coherent narrative of who it used to be. Moods and techniques vary accordingly, one moment rhapsodizing in sunshine while the next sinking into the depths of some forgotten, nocturnal lake.

Although Los Recuerdos (1998) would seem to unfold at higher elevations, its plumbing is no less subterranean. With resolute sporadicity, Saluzzi-via-Lavandera (that the composer was present at the recording session is obvious, even without the candid liner photos confirming this) dabs from a psychological palette. A colorless abyss provides the backdrop for streaks of yellow and brown, splashes of red and lavender, and the occasional sparkle of gold. But the default is something far cloudier, a hue that cannot ever seem to settle on one constitution. In a supplemental liner note, guitarist Pablo Márquez, who like Saluzzi grew up around the mountains of Salta, confirms this: “Dino never allows himself to become trapped in one aesthetic; he is always somewhere unexpected.” Said genre-defying style only adds water to the composer’s stream of consciousness. His notecraft oars its way into the moonlit inlet of Media Noche (1990) and docks at the misty way station of Vals Para Verenna (1987) with equal attention to detail. Even the minute-long etude Moto Perpetuo (2000) is no less rich in imagery and association. Márquez’s sentiments further emphasize Saluzzi’s affinity for storytelling. In such pieces as La Casa 13 (2002) and Donde Nací (1990), one can feel his thick approach to description. Others, such as Romance (1994), which in its tuneful brevity relates the oldest story of them all, and the Satie-like Claveles (1984), come across as songs in search of words, even as they content themselves with mere hints thereof.

But as the program evolves in self-conscious order, slender shards of nomination cohere into wider scenes by the glue of minimal vocabularies. The majestic peaks of Montañas—which, having been composed in 1960, is the earliest of the ten—reach skyward with resolution of a younger soul, one who carves with fists over chisels yet who in doing so affords through the grime of experience that much more to consider.

From these portals of reflection, Lavandera emerges as a storyteller in his own right with pianism at its most impressionistic—which is to say: indelible.

(To hear samples of Imágenes, click here.)