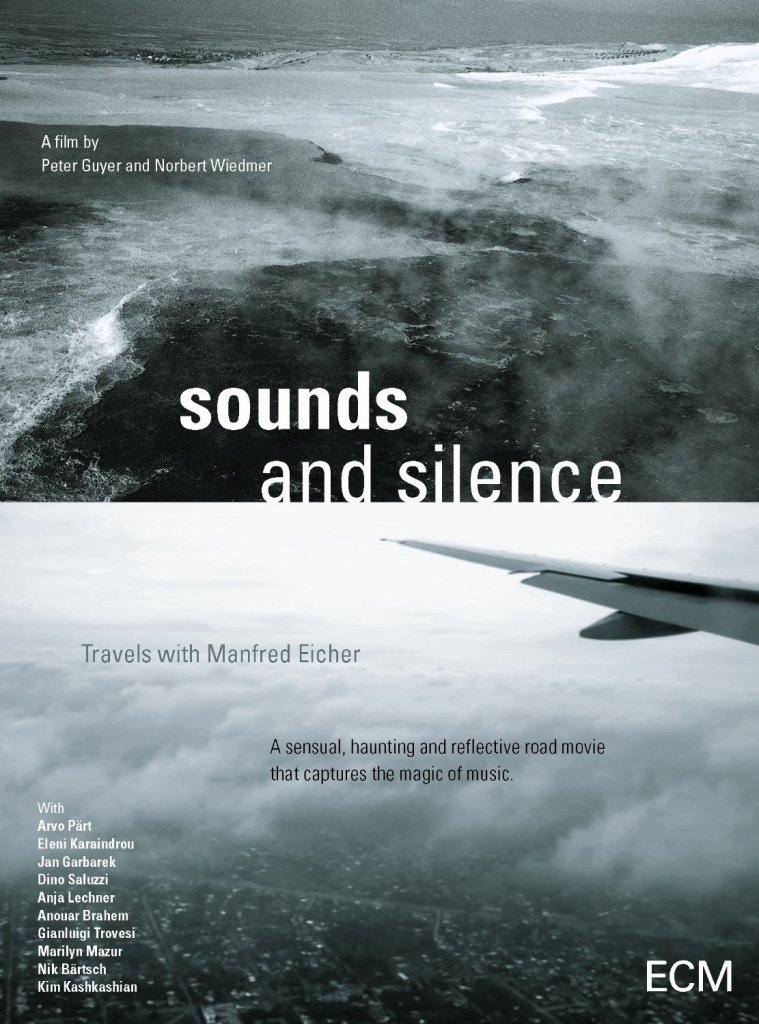

If every film has a soundtrack, does it not stand to reason that every soundtrack has a film? This would seem to be the guiding question behind Sounds and Silence. In this unprecedented DVD release, documentarians Peter Guyer and Norbert Wiedmer set out to capture ECM Records as a living entity in which human labor and ingenuity are the dual heart of musical life. Although billed as a “road movie” and patterned by footage of label founder and producer Manfred Eicher in various states of transport, it is equally concerned with the non-literal paths that have led to the creation, sustenance, and influence of the German imprint and its ongoing permutations. They keyword here is “ongoing,” because Eicher and his trust have only intensified their productivity since 1969, when it all began, to the point of releasing, on average, an album per week.

It is almost inevitable that the film’s opening montage and credit sequence should be accompanied by a recording of Keith Jarrett. The pianist is one of ECM’s brightest stars, but is also committed to the power of simplicity, as demonstrated in his rendition of Georges I. Gurdjieff’s “Reading of Sacred Books.” It is an apt description of the filmmakers’ and their process, tasked as they are with interpreting an archive of such magnitude that not even a collective documentary on each album could hope to articulate it. Rather, they must choose to concentrate on specific times, places, and moods in the hope of tapping into something essential to them all. That being said, when Eicher talks of seeking the luminosity of music, which like a comet’s tail leaves behind a pure trace of its being, and philosophizes that music “has no fixed abode,” we begin to realize that such technology of capture as the camera is forever limited in its relationship to the audio realm. For while images suggest associations by their very existence, sounds thrive on the nourishment of our wildest interpretations. Consequently, this film is not so much a behind-the-scenes manifesto of artistic creation as it is a gentle visualization of ECM’s inner heart and its ripple effect across oceans.

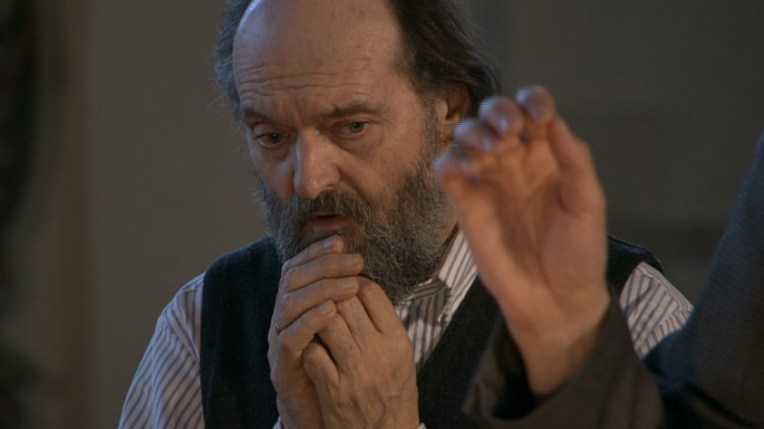

(Manfred Eicher and Arvo Pärt)

Rehearsals with Estonian composer and New Series darling Arvo Pärt at St. Nicholas’ Church in Tallinn yield the documentary’s first proper footage and serve as touchstones for its narrative arc. They offer a strangely profound glimpse into the countless intangibles that go into any ECM recording, but particularly those in which the composer is present, at once presiding over and deferential to the equally intangible magic of a committed performance. Pärt is every bit the contemplative human being one might expect. He feels music with every fiber of his being, and it’s a gift to witness, if only briefly, his childlike sagacity. His face is a veritable gallery of expressions, each attuned to a change in the score and the possibility of making it grow even further toward an unattainable perfection.

(Pärt listens intently as conductor Tõnu Kaljuste’s right hand threads the proverbial needle)

During one such scene, a most touching development occurs when, in mutual happiness, Pärt engages Eicher in a dance. This single gesture reveals something perhaps unexpected in both men: in the composer a feeling of bliss that many of us lose in the name of adulthood, in the producer a love for the simple pleasure of forces aligning in exactly the way he wants. Eicher is indeed a guide of uncompromising integrity, and his smile reveals far more about why he does what he does than the iconic and relatively frequent photos of him hunched over yet another mixing board. True dedication to one’s craft, these images suggest, requires not only a seriousness of heart but also a frivolity of spirit.

(Eicher and Pärt share a dance to the tune of the latter’s Estonian Lullaby)

Between these signposts, we encounter a train of faces and voices, many perhaps for the first time. Interviews with Pärt and his delightfully honest wife Nora, Greek composer Eleni Karaindrou, Tunisian oudist and composer Anouar Brahem, Italian multi-reedist Gianluigi Trovesi and accordionist Gianni Coscia, Argentine bandoneón master Dino Saluzzi, and Eicher himself help us better understand the inconceivable alignments of fate that sometimes must occur just to bring the right people together, much less allow them the space to create whatever they will create. The bellows of Saluzzi’s lungs, for example, prove just as eloquent as those between his fingers when he shares his history as a musician who shunned the academy in favor of raw expression. In him is revealed an educator’s heart, one that seeks to learn as much as enhance learning in others. Brahem is likewise an articulate soul possessed of a subtle wit. His sensitivity toward political matters only serves to enhance appreciation of his sonic endeavors, which in light of his worldview take on new valences of awareness and pacifism. It’s a joy to watch him alone in his home studio, building his tunes, element by element.

As we navigate environmental flashes of Eicher’s travels, we follow the producer to Athens for a monumental performance of Karaindrou’s music (of which he shadows a rehearsal with saxophonist Jan Garbarek and violist Kim Kashkashian), a recording session at Studios La Buissonne in southeastern France with Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin (and the intuition needed to bring out just one muted string hit in post-production), another at Copenhagen’s Sun Studio with Marilyn Mazur, a concert featuring Brahem with pianist François Couturier and accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier at the Prinzregententheater in Munich, and mixing Trovesi’s explosive reconstructions of operatic favorites in Bergamo, Italy. Other highlights include footage of said concerts, a brief sojourn to Argentina with Saluzzi and Lechner, some candid moments with the ever-animated Trovesi and his confederate Coscia, and even a peek into ECM’s Munich headquarters, where we see everyday logistics in action, including the meticulous process of selecting album covers.

In the same way that Eicher seeks to put the listener inside the music, so do the filmmakers try to put us in ECM’s world, and in that spirit we end where we began: with Pärt. Experiencing the consummation of every above-mentioned force is one of the most gratifying passages of the film. The music is the message, because the message exists to be sung.

ECM’s music has always approached the level of cinema, and so it was only natural that it should be honored in moving pictures. And yet, the end result seems more like the realization of a fantasy than a picture of reality. Throughout the 87-minute duration, the filmmakers make as much as they can out of what little they have. Case in point: Saluzzi and Lechner’s Argentine sojourn. Aside from a hint of social awkwardness, the footage overlaps with another film by co-director Wiedmer (see El Encuentro, also released on an ECM-edition DVD) and is perhaps better saved for that portrait. Its inclusion here feels like recycling and not in the documentary’s best interest.

Another dividing point may be the lack of attention paid to certain other production aspects. Early on in the film, Pärt speaks sagaciously of the recording session as an organism, of which musicians, engineers, and producers are vital organs. And yet, what of those unsung engineers? While of course ECM has none under its employ (they are independent artists working for independent studios), Martin Wieland, Jan Erik Kongshaug, Stephan Schellmann, Peter Laenger, James A. Farber, and, more recently, Stefano Amerio, among others, have all been of vital importance in shaping the label’s distinctive identity. The reality, of course, is that such a film, regardless of maker, can at best only be supplementary and will be of far more interest to the ECM fan than to someone unfamiliar with the label. Nothing can replace the listener. And is that not what Eicher is, above all? Why else would we first encounter him on screen as a man alone with his thoughts, as if listening to the world?

And so, it is in the name of listening that I direct your regard to the film’s soundtrack.

A cover that brings to mind Iro Haarla’s Vespers situates us in a cloud-break with only a snatch of landscape below to indicate the separation of worlds. The composition is emblematic of a label that has always charted indefinable borders between civilization and emptiness, and in so doing has made music seemingly aware of its own mortality. Keith Jarrett’s “Reading of Sacred Books,” written by Georges I. Gurdjieff, asserts nothing but its own lack of assertion. It is instead an expression of transcendence, a confirmation of the energies all around and within us, by which we are able to produce this wonder called music in the first place.

If anything can be said to define ECM’s output, it is memory. Charting that which has already passed in order to open our eyes to that which has yet to come, these musicians have all primed us for the opening of newer doors. This is the spirit of the label: to take the musical moment and craft it into self. Few tracks on this compilation embody this spirit more creatively than “Modul 42” from Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin. After gaining access to the recording process in the film, it’s wonderful to encounter the music on its own terms, to look deep into its eyes and know it’s looking back at (and through) us. The sparkling middle passage ushers us into a world hitherto unknown yet undeniably familiar. Anouar Brahem’s “Sur Le Fleuve” is another slice of magic. Featuring the same trio combination of piano, accordion, and oud as recorded in the film, its marriage of instrumental signatures is nothing short of breathtaking. We can take great comfort in this music, for it is our partner.

Dino Saluzzi’s “Tango a mi padre” played as close to breathing as possible by him and Anja Lechner, speaks to another facet of that fascination with memory, which in this piece is so alive that it weeps for itself. We might, then, hear Vicente Greco’s “Ojos Negros” at the same duo’s hands with renewed sense of purpose. That these two bodies traveling through space and time have found themselves somehow joined at the soul, sharing with one another the details of their upbringing and the unknowns of their future, is a miracle. Also miraculous are two selections from Eleni Karaindrou, whose compositional fabric is spun from her “Farewell Theme,” which floats Jan Garbarek’s soulful tone across an ocean’s wave of strings, as Kim Kashkashian’s aquatic tail leaves its marks in the water, and “To Vals Tou Gamou,” in which piano, accordion, and violin dance like pens across paper. We may listen to this music either poignantly or through the lens of a joy that remains somehow clear in the mists of its origin.

The “Arpeggiata addio” by Giovanni G. Kapsberger, as heard on Rolf Lislevan’s Nuove musiche, likewise speaks of the past in the present. In it we can feel the propulsion of life experience by the power of desire. A voice carries us across the threshold of then and now, cradled in hands chapped like old parchment. Fresher inkwells spill their contents across Marilyn Mazur’s whimsical “Creature Walk,” a piece which as we know from the documentary brings a smile even to her face, and Gianluigi Trovesi’s blistering take on “Così, Tosca” by Giacomo Puccini. Although lit by a canonical match, Trovesi’s candle burns like an instrument of restless beauty in the macabre waltz funneling around him.

Arvo Pärt is also represented twice. His Für Lennart in memoriam is an undeniably dense molecule of emotional transfixion, while the postludinal Da Pacem Domine, after a reprise of Jarrett’s Gurjdieff “Reading,” carries us on its feathered back to the edges of sunset, where awaits the discovery of discovery.

How does one sum up ECM Records? Thankfully this is the purpose of neither the documentary nor its soundtrack. Rather, they exist to give us glimpses into the ever-shifting structure of the label’s skeleton. Following Manfred Eicher on these journeys, whether through eyes or ears, you might just find yourself wondering how so much external architecture could arise from music that is immaterial, only to realize that it’s the other way around.

(To hear samples of the soundtrack, click here.)

this DVD and CD is one of my ‘all-time’ favorite ECM.

i’ve watched it multiple times, as it’s so good.