This treasure trove among treasure troves from the Old & New Masters series is the definitive archive of Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition. The Chicago-born drummer, notes Bradley Bambarger in the set’s informative booklet, has appeared on more ECM albums than any other session musician. But it’s as a leader that his most enduring marks were made, and we can be sure that this re-release will both revive positive associations in anyone who remembers the albums on vinyl and inspire pristine ones for the digital newcomer. Like the project’s leader, Special Edition was about the joy of energy and the energy of joy, spreading love and music in overlapping measure.

Special Edition (ECM 1152; also included as part of ECM’s Touchstones series)

Jack DeJohnette drums, piano, melodica

David Murray tenor saxophone, bass clarinet

Arthur Blythe alto saxophone

Peter Warren bass, cello

Recorded March 1979 at Generation Sound Studios, New York

Engineer: Tony May

Produced by Jack DeJohnette

There could hardly be a more apt title for the inaugural effort of Jack DeJohnette’s most influential project. As in his formidable collaborations with Keith Jarrett and Gary Peacock, DeJohnette kneaded enough preservatives into this album to keep it as fresh as the day it was baked. Special Edition also served as a launching pad for reedmen David Murray and Arthur Blythe, both onetime members of the World Saxophone Quartet and poster children for the post-bop generation. Their edgy expositions nest seamlessly into the present company. “One For Eric” kicks off the set with a swinging bang as alto sax and bass clarinet inhabit the right and left channels, bass and drums dancing between them with the Neo-Classical ebullience for which the track’s namesake, Mr. Dolphy, was so well known. Jumping from one visceral solo to another (Murray on a notable roll here), the group traces the fine edge between groove and abstraction with the skill of Philippe Petit on a wire. This tasty appetizer prepares us for the largest course in “Zoot Suite,” an instant classic that has since become a touchstone of DeJohnette’s repertoire. A masterful weave of raw horn vamps and somber asides, it is equal parts jubilee and dirge. Peter Warren keeps the beat throughout and makes sure his bandmates never hibernate for too long. “Journey To The Twin Planet” applies heavy mystique to this musical visage, grinding across the skin like the detuned bass at its foundation. DeJohnette introduces a dazzling free-for-all that works its way into mind and body with equal alacrity. The album rounds out with two Coltrane covers. “Central Park West” is a beautiful ode strung along by arco bass and detailed by liquid reeds, while “India” opens pianistically and runs through a stellar turn from Blythe before settling into a smooth rejoinder.

Were I to classify this album, I would unhesitatingly file it under “Zombie Jazz,” for it walks like the living dead, enchanting us with its embodied blend of natural and unnatural movements. There is something hard won about this music that makes it all the more engaging. Agitation has rarely sounded so fantastic.

<< Haden/Garbarek/Gismonti: Magico (ECM 1151)

>> Ralph Towner: Old Friends, New Friends (ECM 1153)

… . …

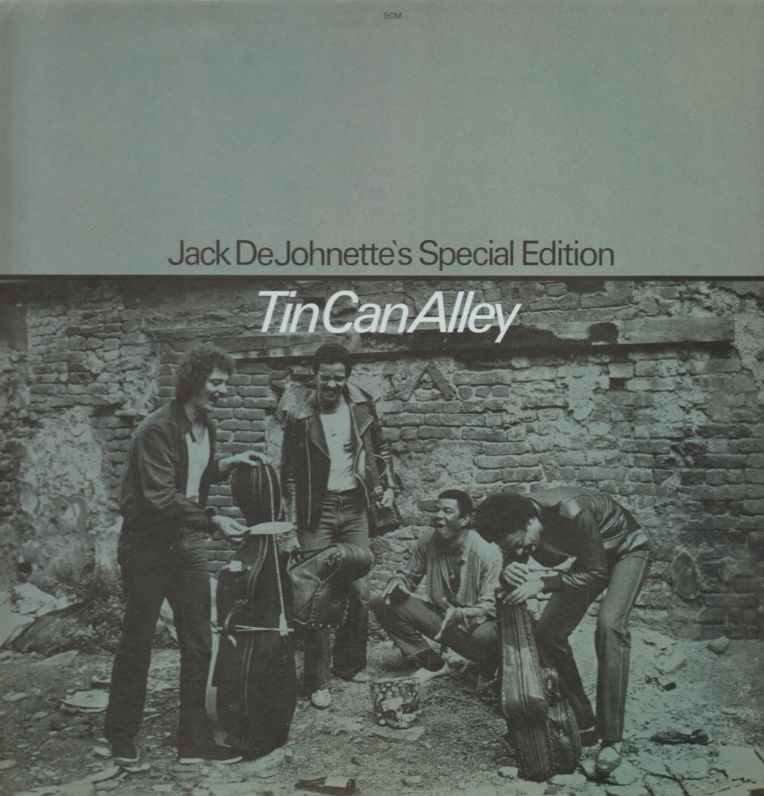

Tin Can Alley (ECM 1189)

Jack DeJohnette drums, piano, organ, congas, timpani, vocal

Chico Freeman tenor saxophone, flute, bass clarinet

John Purcell alto and baritone saxophones, flute

Peter Warren bass, cello

Recorded live at Studio Bauer, Ludwigsburg, September 1980

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

“One, two, you know what to do.”

Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition came up with another winner in this second ECM joint. Most of the blood of Tin Can Alley flows through the work of reedmen Chico Freeman (on tenor sax and bass clarinet) and John Purcell (on alto and baritone). Their voices—one rich with soul, the other provocative—define the title track. With the machine-gunned obbligato of DeJohnette and Warren covering their backs, they unhinge themselves. An epic baritone solo from Purcell drops the heaviest weight on the scale. These dialogues continue down the ramp of “Riff Raff,” even as Warren drops a heavy dose or two of his own. DeJohnette keeps tabs on every shift, all the way to his lusty swing in “I Know,” where a simulated crowd embraces his unbounded vocals. He also has a solo track, “The Gri Gri Man,” a veritable smoothie of congas, cymbals, toms, and organ. The occasional boom of timpani adds chunkiness to the texture.

Our journey through Tin Can Alley would be far from complete without “Pastel Rhapsody.” Another dialogue, this time between flutes, blends into a piano solo, which in its quiet manner paints the darkness with a meteor shower. From this sprouts a brassy stem, unfurling leaves and petals to the tune of something beyond our ken. Downright cosmic, and one of the most direct-to-heart ballads of the entire ECM catalog.

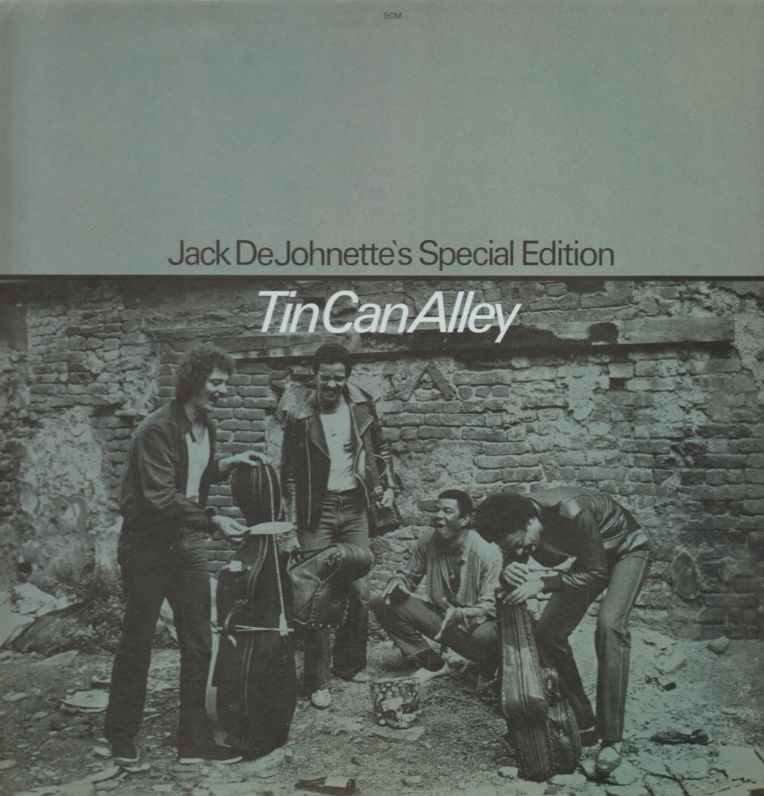

As with each of DeJohnette’s Special Editions, the cover photo is emblematic of the band’s free spirit, making music for the sake of its rewards. So if you happen to find yourself in this alley, they would much rather you stick around and feel what they’re doing than simply drop a dollar and move on.

<< Arild Andersen: Lifelines (ECM 1188)

>> Pat Metheny & Lyle Mays: As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (ECM 1190)

… . …

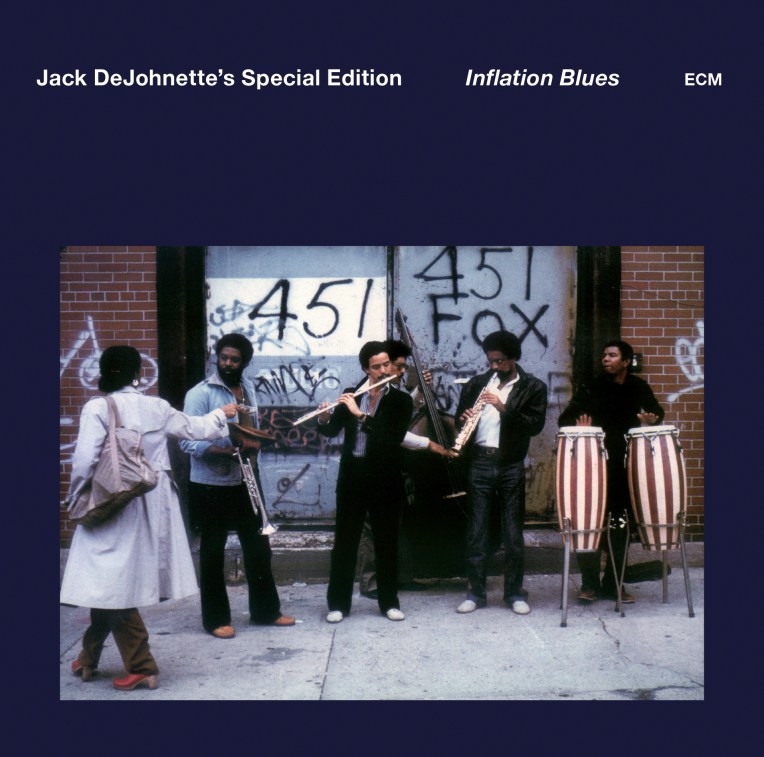

Inflation Blues (ECM 1244)

John Purcell alto and baritone saxophones, flutes, alto clarinet

Rufus Reid bass, electric Bass

Chico Freeman bass clarinet, soprano and tenor saxophones

Baikida Carroll trumpet

Jack DeJohnette drums, piano, vocals

Recorded September 1982 at Power Station, New York

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

For its third ECM outing, Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition incorporates the robust sound of Baikida Carroll, who lends his trumpet to four out of five tunes, all composed by our gracious frontman. “Starburst” drops us from the sky into Freeman’s didgeridoo-like bass clarinet of Freeman as Rufus Reid stretches his bass like a tectonic rubber band through a steady drum riff. Intriguing crosshatching of tenor (Freeman) and alto (Purcell) saxes makes for a lively combination. Purcell also provides excellent baritone traction in the album’s closer, “Slowdown,” which capitalizes on its promise only in the last stretch and ends in noteless clarinet breath. An infectious twang-and-slide pattern locks us into its groove from the start. “The Islands” is an amalgamation of influences and impressions, the glare of sun and sands healed through the surgery of improvisation. Its abstract couplings of winds and horns lead to a delicate but enraptured drum solo. The title track gives us more of what we might have expected from the last: a smooth Reggae flavor. DeJohnette provides the requisite staccato of a clavinet while singing this timely lament:

A dollar’s worth about thirty cents

You’re working your behind off and you still can’t pay the rent

The more money you make, the more Uncle Sam takes

And the unions still cry for more dues

Poor people stay poor; they’re defenseless and sore

They cry out of frustration against a sad situation

Breeds hunger and strife, and a miserable life

And you know the politicians aren’t even bruised

But they won’t find the solutions to win this confusion

That’s why I sing these inflation blues

Tenor and alto add diffusive commentary to the repeat before playing us out bittersweetly. The absence of trumpet is keenly felt in the ornamental “Ebony,” which lands us in the album’s plushest diversions. Freeman’s gorgeous soprano provides the first solo over DeJohnette’s rims and piano. A rubato structure molds each melodic cell like a bead on a wire, Purcell and Reid turning out a fine solo apiece before closing in the fluted and jaunty fade.

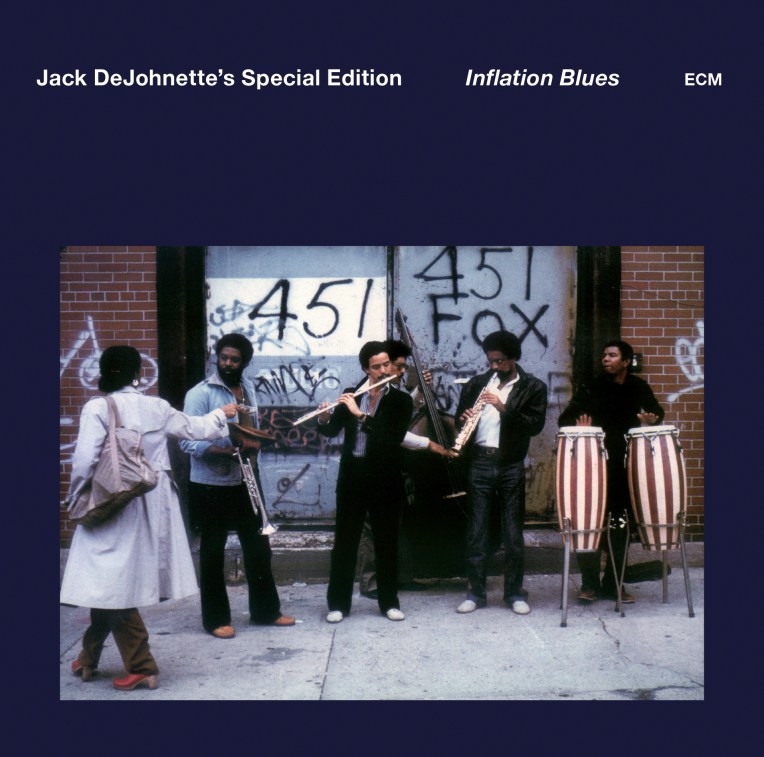

The cover is another classic one and expresses the band’s humility and commitment to its roots. Like the single dollar bill being dropped into Carroll’s hat, the least compensation we can offer is our undivided attention to this consistently engaging set of down-to-earth music. Then again, if the last album taught us anything, our least isn’t worthy enough.

<< Walcott/Cherry/Vasconcelos: CODONA 3 (ECM 1243)

>> Michael Galasso: Scenes (ECM 1245)

… . …

Album Album (ECM 1280)

John Purcell alto and soprano saxophones

David Murray tenor saxophone

Howard Johnson tuba, saxophone

Rufus Reid bass

Jack DeJohnette drums, keyboards

Recorded June 1984 at Power Station, New York

Engineer: David Baker

Produced by Jack DeJohnette

An exercise in exuberance in memory of his late mother, Album Album opens with one of DeJohnette’s most sophisticated compositions ever committed to disc: “Ahmad The Terrible.” With an engaging klezmer-like joie de vivre and fantastic sopranism from Purcell, it delights from start to finish. The first of five originals, it leaps from the speakers like a body in motion. As if that weren’t jubilant enough, “Festival” stirs up a crowd’s worth of enthusiasm, made all the more inspiring through spirited drumming. “New Orleans Strut” makes tongue-in-cheek use of drum machine as DeJohnette plays a synth lead (his pianism in the opener is also worth noting). Over this bubbly layer the punchy stylings of both reedmen work their way from the groove in most visible fashion. Such is the case in “Third World Anthem,” another sophisticated peak. Playful whoops from horns add a strong emotional undercurrent toward the elegant, staccato finish. “Zoot Suite” makes a welcome cameo, cut in half from its first appearance on Special Edition. Here it is delicate, but with no loss of groove to show for it. The one compositional outlier is “Monk’s Mood,” in which horns and bass dance cheek-to-cheek as if in an old Hollywood black-and-white. It also engenders the album’s only blatant lapse into unrequited joy through the baritone of Howard Johnson.

The verve of DeJohnette and his bandmates keeps us anchored amid a flurry of glorious activity and, alongside Reid’s tight bassing, allows little time for sadness. Here is a space in which mourning must wear a smile, where the self is always secondary to those one loves.

This is primetime creation with late-night attitude, fantasies turned realities by musicians who care about everything they touch through their refusal of false appearances. By looking into this mirror, we might just see more of ourselves than we know, because the freedom of DeJohnette’s networks far predates the social ones in which we are now so deeply mired. Herein lies a lesson in art: those who laugh only at others know too little, those who laugh only at themselves know too much, and those who laugh along with others know all they need to know. There’s too much badness in the world to ignore the possibilities found in what’s left behind. In this regard, few releases stress the virtue of reissuing as much as this one. A special edition indeed.

<< Egberto Gismonti/Nana Vasconcelos: Duas Vozes (ECM 1279)

>> Michael Fahres: piano. harfe (ECM 1281 NS)