As ECM producer Manfred Eicher tells Ethan Iverson in the booklet that accompanies this timely Old & New Masters edition, Paul Motian (1931-2011) was more than a drummer. He was also a poet. Motian had a sense about the pen which, like his impulses at the kit, never bothered to obsess over the whole picture. He was more concerned with the bare minimum pieces to indicate the theme of any puzzle on which he laid hands. That was enough for him. The six albums collected here are therefore to be taken not as a grand narrative or musical résumé, but as four border pieces and two middles. That should be enough for us.

It is significant that the cover art for this set—part of ECM’s coveted Old & New Masters series—should break the trend of previous releases, all of which are clothed in minimal text against white backgrounds. The image originally jacketed Conception Vessel, an album conceived at the express behest of Eicher, who encouraged Motian to lead his debut album as composer and leader in 1972. So began a four-decade relationship, of which only a fraction is represented in the present collection. Its radial design may be read as a sigil for the man himself: a creative sun whose light abandons center for periphery.

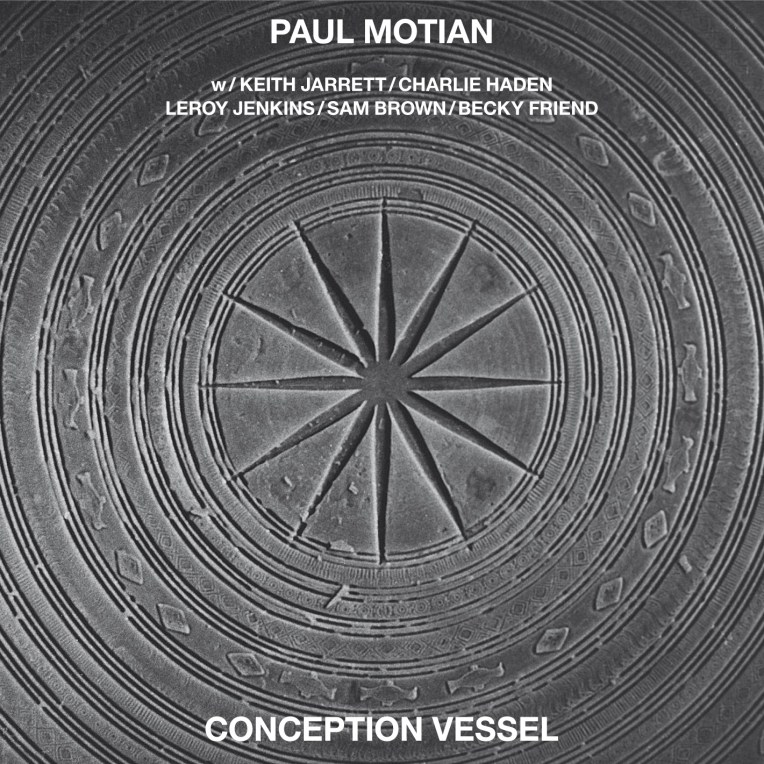

Conception Vessel (ECM 1028; also included as part of ECM’s Touchstones series)

Paul Motian percussion

Keith Jarrett piano, flute

Charlie Haden bass

Sam Brown guitar

Leroy Jenkins violin

Becky Friend flute

Recorded November 25/26, 1972 at Butterfly and Sound Ideas Studios, New York

Engineers: Kurt Rapp and George Klabin

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Considering that Paul Motian was 41 when he recorded Conception Vessel, it’s clear to see why his disposition was so amenable to the dawn. As a human being, his voice had already come into its own and needed only the blessing of the score to give it shape without words. Then again, there are the titles, which for all their naked evocativeness retain an enigmatic patina. “Georgian Bay” congeals with the steady plucking of guitarist Sam Brown, who cuts a striking, if subtle, figure across the album’s filmic canvas. Supported only by a smattering of cymbals and Charlie Haden’s crab-walking bass lines, the tune betrays little of Motian’s prowess, saving it instead for “Ch’i Energy,” a flurried solo through which his centrality blossoms in non-confrontational power. This makes the looser affair of “Rebica” all the more lyrical. Haden is in peak form in this guitar-bass-drums setting. One moment finds him providing ground support, while in the next he has already ventured off into more airborne ruminations. Brown returns after a pensive resistance, flirting with the music’s surface like a drowsy Derek Bailey. The title track raises the curtain for Keith Jarrett’s spotlight, which strangely does little to change the album’s surface texture. Despite a lack of (discernible) melody, the interplay between piano and drums yields talented ramifications. Though not the easiest piece of music to put one’s finger on, Jarrett’s fiery exuberance as he whoops his way along makes it one of the most intriguing cuts on the bill. The flute and percussion of “American Indian: Song Of Sitting Bull” draw up a suitable contract for the pianist’s wind-work in combination with Motian’s rattlesnake maracas. “Inspiration From a Vietnamese Lullaby” adds bass and the violin of Leroy Jenkins to the same in the interest of new improvisatory heights. These are exactly the kind of rituals that Jarrett lived for in the 70s (see his recently unearthed Hamburg ’72, also with Haden and Motian), and the oracle-like qualities of their architecture hold up well beneath the weight of time.

Despite being headed by a drummer, Conception Vessel eschews the trappings of mundane grooves as indication of Motian’s lifelong mapping of branches over roots. The jacket art again proves instructive, describing a sound oriented toward invisible directions yet which is also mothered by the soil. It is furthermore a worthy example of ECM’s early sound and openness to those at the head of the line who share the label’s ongoing passion for pushing, if not defining, boundaries.

<< Dave Holland Quartet: Conference Of The Birds (ECM 1027)

>> Garbarek/Andersen/Vesala: Triptykon (ECM 1029)

… . …

Tribute (ECM 1048)

Carlos Ward alto saxophone

Sam Brown acoustic and electric guitars

Paul Metzke electric guitar

Charlie Haden bass

Paul Motian percussion

Recorded May 1974, Generation Sound Studios, New York

Engineers: Tony May and Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Motian’s second ECM project finds the multitalented drummer-composer in comforting repose. Transcending the pianistic sound that mystified his earlier efforts, Motian pulls in the loose strands of guitarists Sam Brown and Paul Metzke to his ever-expanding loom. Bookending the set are two Brown/Haden/Motian trios. The flowering classical guitar and tenderly applied drumming of “Victoria” provide a magnetic backdrop for Carlos Ward’s smoldering alto, all the while developing into a snapshot of urban night. One imagines Brown sitting on a balcony ledge, drawing from the squalor below (where Ward plays on a streetlit corner) a most soulful evocation of the dark’s hidden messages. Clouds part, but reveal no stars. Haden’s “Song For Ché” is even more somber. Ward’s absence makes room for the composer’s gorgeous solo as maracas slither by with the grace of a rattlesnake in a rather distanced version of this major tune. Ornette Coleman’s “War Orphans” is the nucleus of the album. Soulfully rendered and lovingly arranged, it drifts in on a tide of history. Our frontman shines in “Tuesday Ends Saturday,” a more blatantly post-bop affair that slides briefly into brighter days. Amplified guitars converge like a doubled Marc Ribot before careening their separate ways, even as heavy cymbal crashes from Motian threaten to drown out the other instruments (clear separation in the recording, however, ensures this never happens). Which leaves us with “Sod House,” a crepuscular and blurrily moving image in which guitars ride a crest of bass and drums.

Astute extemporization and feel for melody make this one of ECM’s most evocative first-decade releases. Motian finds songs in every instrument. He gives us little indication as to who or what the album is a tribute to, but I suspect it need be nothing more than a tribute to the journey of making music, and to the indomitable spirit of an art form that is forever unpacking itself along the way.

<< John Abercrombie: Timeless (ECM 1047)

>> Keith Jarrett: Luminessence (ECM 1049)

… . …

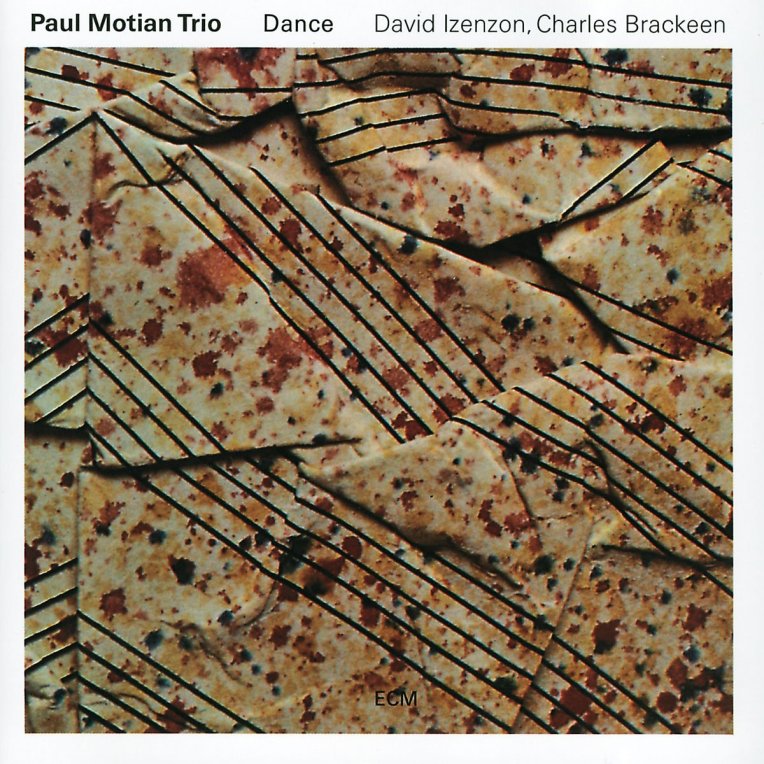

Dance (ECM 1108)

Paul Motian drums, percussion

David Izenzon bass

Charles Brackeen soprano and tenor saxophones

Recorded September 1977 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

In 1977, Motian set a new precedent when, with this first trio album, he loosed his brand of chamber jazz into the world. The late David Izenzon on bass and fellow Coleman cohort Charles Brackeen on reeds completed the package, tied up nicely with six of Motian’s engaging compositions. The titles thereof seem only loosely linked to their denouement, assuming they were ever meant to be descriptive in the first place. Either way, the results are so visceral that headings need not apply.

Brackeen is primarily known as a tenor player, but on Dance he employs the soprano almost exclusively. The only exception is in the penultimate “Prelude,” where at last we get a blast of his guttural métier for a marked change in diction. It writhes with the power to deepen the trio’s abandoned sound from sweeping agitation to smoky elegy in a single change of embouchure. Contrast this with the Garbarek-like salutations of “Kalypso” or the relaxed sopranism of “Asia,” which walks a trail of meandering beauty that is the album’s calling card. As can be expected, there are intenser moments to be had, as in the tight squeals of the opening “Waltz Song” and the wilder forays of the title cut. The latter also offers some fine duo-ship with Izenzon as well as with Motian, who seems to drop his sticks in great number from varying heights. Through the glitter of “Lullaby” we hear the stars of our slumber turned into song. The bass hints at a long-dead groove in which we can only grasp a sliver of faded glory. We revel instead in its ruins, where the dance really takes place. There, it is the bass that lulls us, pulling its feet under the covers in a frigid evening, curled like a child hoping to awaken from a bad dream.

Dance is a wayfarer’s song. Yet the trio is passionately disinterested in the wandering itself and has eyes instead for the geographies it has yet to tread. Like a spring that winds itself tighter but never snaps, every melody is packed with lethal energy. The music relies on this tension, compressed like continental plates beneath unfathomable oceans. As land grows scarcer, the musical remainder becomes our vegetations, our lifeways, our civilizations, and we are left standing in the middle, watching as history takes its first steps.

<< Eberhard Weber Colours: Silent Feet (ECM 1107)

>> Dave Holland: Emerald Tears (ECM 1109)

… . …

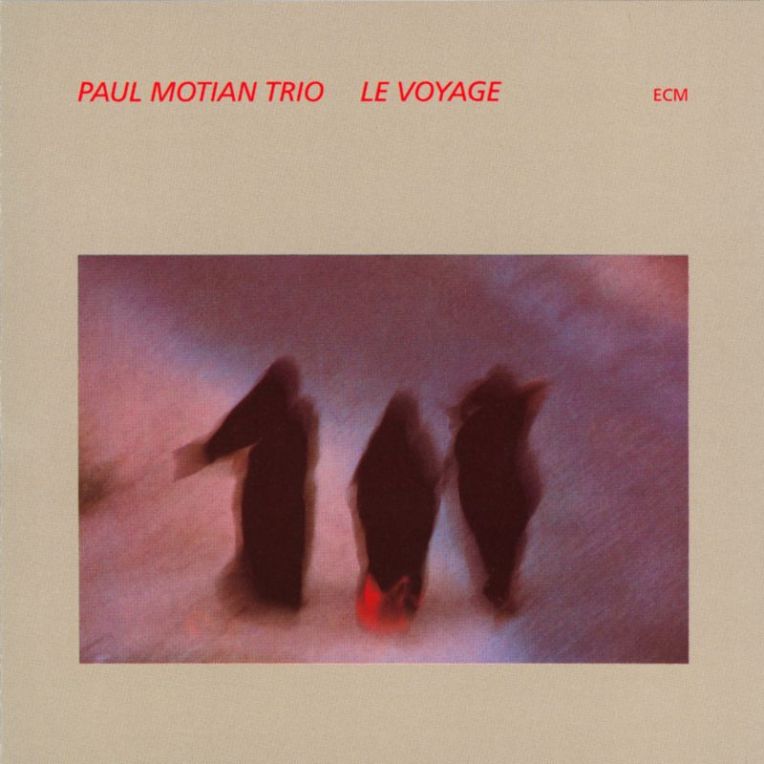

Le Voyage (ECM 1138)

Paul Motian drums, percussion

Jean-François Jenny-Clark double bass

Charles Brackeen tenor and soprano saxophones

Recorded March 1979 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Le Voyage is dear to my heart for opening with one of ECM’s crowning achievements in production, musicianship, and song. As Brackeen’s bluesy soprano in “Folk Song For Rosie” sweeps across that sandy backdrop of bass—courtesy of the late Jean-François Jenny-Clark, replacing David Izenson in the trio’s previous lineup—and Motian’s brushed drums, one can be sure that more beautiful landscapes will be few and far between. The sax fades into the mystical silence from which it arose, making way for gelatinous bassing before a mournful return. A careful selection of gongs and drums awaits in “Abacus,” in which Brackeen dazzles with an enlivening tenor solo. After this detour, Motian breaks into his own erratic asides. The studio miking distances his voice, making it seem as if he were a barely visible conjurer stretching his arms across time and space to produce an impossible array of statements before our very eyes. The arco intro of “Cabala/Drum Music” glides into Motian’s fluttering hands, which bid bass and tenor to speak in themes. Brackeen and Jenny-Clark shine again in “The Sunflower,” pouring a vast oasis of energy into which the final, and title, track dips its feet with measured grace.

Though the title of Motian’s fourth ECM album is in the singular, its results are undeniably in the plural. The unspoken virtuosity required here humbly defers itself to three credos: Melody, Moment, and Mood. Its sounds come to life only behind the closed eyes of a relaxed mind and body. Each solo feels connected to the others, as if by tendon, lighting our inner landscapes with signifiers that over eons blur into one soft and silent flame. This album epitomizes the “ECM sound,” even as it transcends all such arbitrary categories in favor of a more immediate form of communication that looks beyond the physical self and into the translucent thread that connects it to all else.

Those looking for a groove may want to move on, but do so at their own peril, for they will be missing out on one of Motian’s finest.

<< Eberhard Weber: Fluid Rustle (ECM 1137)

>> Mick Goodrick: In Pas(s)ing (ECM 1139)

… . …

Psalm (ECM 1222)

Paul Motian drums

Bill Frisell guitar

Ed Schuller bass

Joe Lovano tenor saxophone

Billy Drewes tenor and alto saxophones

Recorded December 1981 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The Paul Motian Band, short-lived in the incarnation captured here, enables a curious experience with Psalm. “Motian” may as well mean “mystical,” for such are the turns that await the curious listener. It’s not that he has access to some hidden pocket in the ether, from which he pulls a wallet of compositional currency. He simply trusts in his fellow musicians enough to follow wherever they might lead. And what a group to be led by. Between Joe Lovano’s singing tenor and the serpentine licks of guitarist Bill Frisell, not to mention an infusion of supremely warm engineering, even critical listeners are sure to find something of intrigue.

Some of the album’s landscapes, like those of the lush title track and “Fantasm,” cultivate a heat-distorted crop of pliant reeds and guitars. One is tempted to read dreams into them, when in fact nothing can be so fleeting as those enigmas that already make life even less graspable. Such would seem to be the meaning behind titles like “White Magic,” which, despite their serrated edges and deep thematic scouting missions, are nebulous constructions at heart. Other diversions, such as “Boomerang” and “Mandeville,” have Frisell written all over them, to say nothing of his solo “Etude,” a liquid font of melodic wisdom that stretches like an acrobat during warm-up. Motian does occasionally step into the foreground (“Second Hand”), but would rather bask in the viscosity of his own skeletal tunes, and in the tenderness of his band mates’ refractions of them—Ed Schuller’s rosy bass work in “Yahllah” being one example.

Though Psalm may be rightly considered a classic, it doesn’t aspire to be. It is instead an altogether metaphorical experience to enjoy uninterrupted and in total acceptance. These musicians have surely seen more lucid days, but may remember few so enchanting as this.

<< Adelhard Roidinger: Schattseite (ECM 1221)

>> Jan Garbarek: Paths, Prints (ECM 1223)

… . …

it should’ve happened a long time ago (ECM 1283)

Paul Motian drums, percussion

Bill Frisell guitar, guitar synthesizer

Joe Lovano tenor saxophone

Recorded July 1984 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

It was by sheer coincidence that I first heard it should’ve happened a long time ago on the very day I later learned of its leader’s death. The title, therefore, will always be a poignant one for me, as if to say: You should’ve seen him while you still had the chance. And while it saddens me to have to add Paul Motian to the ever-growing list of uncompromising artists I will never experience firsthand (Montserrat Figueras would die one day later), I also feel fortunate to have encountered this awe-inspiring album so late in the game. New music has tended to come into my life only at such times as I’ve been prepared for it, and this album is no exception, for had I heard it even a few years ago I might never have given it a second listen. Suffice it to say when I heard it on 22 November 2011, it left an indelible mark, rendered as an emotional tattoo by the sad news that followed it.

The cast of should’ve is rounded out by guitarist Bill Frisell and saxophonist Joe Lovano, both truly coming into their own at the time of this recording (1984). Lovano’s fluid tenor proves a superb complement to Frisell’s briny swells, positively singing with a dark amethyst tone in the opening title cut. “Fiasco,” on the other hand, foregrounds Frisell, who sounds like a synth in its death throes (all the while making it sing). Meanwhile, Lovano stills this discomfort with heavy inoculations of medical wisdom. This is followed by a gorgeous reprise of “Conception Vessel” that depicts the changes Motian had undergone since the selfsame masterwork had been laid down twelve years prior. One now finds a more internal evocation, brought to the consistency of bubbling lava by Frisell’s quiet heat and Lovano’s pockets of air.

Like the album as a whole, “Introduction” is another dip inward. This somber solo from Frisell primes us for the resplendent territories of “India.” Motian paints an awesome picture, which with each sparkling step brings us closer to its thematic core, traced in relief by Lovano’s lilting horn. “In The Year Of The Dragon” indeed slinks and curls like the long, scaled creature of myth, cutting rhythms across the sky with every whip of its tail. The licks of Lovano’s sax are like the glint of an eye trained curiously ahead, even as its energy radiates through the fields and villages below. Frisell’s picking is at once straight-edged and ess-curved. We end with “Two Women From Padua,” which lays Lovano over Frisell’s breaking circuits—this a mere preamble for gossamer unraveling. Lovano crawls like a spider along Frisell’s webs, strung between those raspy branches of Motian’s drums.

Despite the occasional burst of abstraction, this is a thoroughly relaxing album and one easy to get lost in. The musicians’ talents are affirmed in their restraint. While this may not be the frontman’s most brilliant album, the Motian experience was never about “brilliance,” but rather about openness to the darker corners of the ever-evolving psyche known as jazz. Now that he is gone, may that darkness welcome him into peaceful rest.

<< Chick Corea: Voyage (ECM 1282)

>> David Torn: Best Laid Plans (ECM 1284)