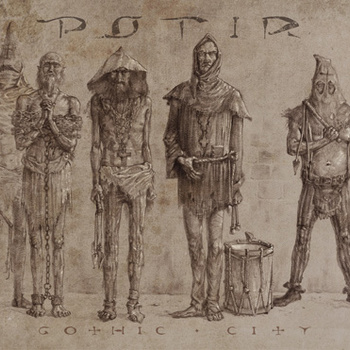

My review of Potir’s medieval fantasy, Gothic City, is now available in RootsWorld online magazine here.

Author: Tyran Grillo

Roby Lakatos Ensemble: La Passion – Live Review

Roby Lakatos Ensemble presents “La Passion”

Roby Lakatos violin

Lászlo Bóni second violin

Jenő Lisztes cimbalom

Lászlo Balogh guitar

Lászlo “Csorosz” Lisztes double bass

Kálmán Cséki Jr., piano

Bailey Hall, Cornell University

April 24, 2014

8:00pm

Thursday night’s performance at Bailey, the last of this year’s Cornell Concert Series, was proof that technology is far less predictable than those who use it. Predictable was the sheer excitement brought to the concert hall by “devil’s fiddler” Roby Lakatos and his all-Hungarian ensemble. How could one not be moved by the balance of incendiary virtuosity and cool programming? Unpredictable, however, was the muddy sound mix, which was prone to distortion and invariably favored certain instruments at the expense of others. Central to, and unique among, those instruments was the cimbalom, a concert hammered dulcimer rarely heard stateside in a live setting and played to captivating effect by one of its greatest living masters, Jenő Lisztes.

It was Lisztes, in fact, who scored the biggest hit of the night with his rendition of Rimsky-Korsakov’s evergreen “Flight of the Bumblebee,” improvising around it with such artful dexterity that it was like hearing it for the first time. With exception of the occasional solo, however, the cimbalom was lost under the weight of pianist Kálmán Cséki Jr. and bassist Lászlo “Csorosz” Lisztes, each miked so loudly that the dulcimer’s gentle edges were frayed beyond recognition. Over-amplification all around also magnified incidental sounds from Lakatos’s bow, often breaking the spell otherwise spun: Sobering reminders that what we were hearing was being processed, filtered and force-fed the sonic equivalent of a 5-Hour Energy drink. Neither music nor musicians needed any such enhancement, and the decision to rely on it seemed as much motivated by virtue of playing in such a large venue—instead of, for example, the restaurant in Brussels where, from 1986 to 1996, Lakatos’ talents drew collaborators and admirers (Sir Yehudi Menuhin among them) from far and wide—as by a need to balance sound levels to the musicians’ liking. Indeed, in light of their most recent live CD of the same music, which fares hardly better, it’s clear they were hearing things very differently on stage, surrounded as they were by monitor speakers fanned away from the audience.

(See this article as it originally appeared in the Cornell Daily Sun.)

Thomas Strønen: Parish (ECM 1870)

Thomas Strønen

Parish

Fredrik Ljungkvist clarinet, tenor saxophone

Bobo Stenson piano

Mats Eilertsen double-bass

Thomas Strønen drums

Recorded April 2004 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Parish, in title and in name, presents one of a handful of side projects by the prolific jazz drummer and composer Thomas Strønen, who along with reedman Fredrik Ljungkvist, pianist Bobo Stenson, and bassist Mats Eilertsen elicits a holistic brand of chamber jazz. This is Strønen’s first appearance on ECM. His collaborations with saxophonist Iain Ballamy as Food have since yielded two further albums for the label—Quiet Inlet and Mercurial Balm—both of which forge a more ambient, electronically savvy sound-world. Here the emphasis is on acoustic textures, soft yet sure in their possibilities.

Admirers of Paul Bley will feel right at home in the delicate suspension bridges walked from beginning to end. Accordingly, the album builds on crystalline foundations, each impulse a new spine jutting from the core. Most of those impulses take form spontaneously, as in the three “Improvisations” peppered throughout. In them are wrought the band’s artistic strengths: Ljungkvist’s charcoal, Eilertsen’s primary colors, Strønen’s filigree, and Stenson’s pointillism. Ljungkvist swaps clarinet for tenor saxophone for a few of these canvases, including the rubato “Daddycation” and the shot-of-espresso happiness of “In motion,” which swings as if simply to prove that the group can, although he seems to prefer the darker reed.

Combinations range from solo (“Travel I” and “Travel II” feature Strønen shifting across colorfully percussive terrains) to trio and full quartet combinations. Of the latter, “Quartz” is an especially enchanting example. Not only does it deepen the crystal metaphor; it also, more than any other portion of the album, grows beyond the sum of its parts. The four-part “Suite For Trio” elides the bass for a significant spell, tripping but always regaining equilibrium on its way toward the veiled final movement. This is complemented by “Easta,” which evokes the mythology of the standard piano trio, thus laying fertile ground for incantation. Like the track “Nu” that concludes things, it signs it name with a splash of melody—just enough to whet the appetite.

Sparse but never deflated, Parish balance in negative spaces and hugs the ether as a parent would a child, waiting for the quiet reciprocation of having been heard.

Miki N’Doye: Tuki (ECM 1971)

Miki N´Doye

Tuki

Miki N’Doye kalimba, tamma, m’balax, bongo, vocals

Jon Balke keyboards, prepared piano

Per Jørgensen trumpet, vocals

Helge Andreas Norbakken percussion

Aulay Sosseh vocals

Lie Jallow vocals

Recorded 2003-2005 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Kjartan Meinseth

Mixing: Jan Erik Kongshaug, Kjartan Meinseth, and Miki N’Doye

Produced by Miki N’Doye and Jon Balke

Tuki is the song of one given to many. As the ECM leader debut of master drummer Momodou “Miki” N’Doye, it houses multiple fates under one roof and collates them into discernible rhythms and voices. N’Doye hails from Gambia, where in the mid-70s he met Norwegian musician Helge Linaae. This encounter brought him to Oslo, where, after coming into contact with such influential movers as Jon Balke, his future as shaker in the far north was secured. Later projects led him to the company of Per Jørgensen, as part of the band Tamma. He was also fortunate enough to collaborate with Ed Blackwell and Don Cherry in the twilight of their careers. N’Doye has since lent his signature to a number of sonic happenings, many with Balke at the helm. In the latter vein, one feels his presence most vividly on Batagraf’s Statements. Tuki joins him once again with Balke and associates, adding to those ranks Gambian vocalists Aulay Sosseh and Lie Jallow, also fixtures in the Scandinavian scene.

In spite of the associations one might attach to N’Doye’s traditions, it is important to avoid mythologizing this music. The elements of which it is composed come straight from the ground, as is apparent in the introductory incantation, which enlivens the air with its percussive kalimba framework, a running theme (and sound) throughout the album’s winding path. At this point the music is still a hut without thatch, a stick frame that allows wind to flow through and speaks of habitation before its walls and roof are fleshed. Thus is the album’s space set up and rendered, given shape by hand and mouth.

Indeed, the improvisational song-speech of “Jahlena,” “Osa Yambe,” and the title track follows the sun’s path without deviation, effectively compressing an entire day into few minutes’ time. Yet N’Doye verbalizes most through his kalimba, the buzz and twang of which form a rougher though no less perfect circle throughout. Pay close attention, for example, to “Kokonum,” and you will hear that he plays the thumb piano as if speaking. Communicative impulses come about through every contact of body and instrument. With stamping of feet and drinking of rain, Jørgensen’s trumpet is now a vulture, now a snake, blind yet attuned to every blade of grass. Jørgensen casts similar atmospheric nets wherever he appears, traveling between the musicians with a rounded blade that bonds even as it severs. Balke’s ambience, for the most part, flickers at camp center. His presence meshes best at the piano, pairing intuitively with kalimba—for what is the former if not the latter’s simulacrum?

Intermingling of the acoustic and the electric, which admittedly takes some getting used to, reaches noticeable synergy in “Loharbye.” In its cage one may hear Scott Solter, a little Jon Hassell, and of course Batagraf rattling around to organic effect. Such transmogrifications speak to the power of context to join continents. In light of this, you may want to check out Statements for a broader sense of the possibilities. N’Doye is more of a storyteller than a singer, and his kalimba loops are minimalist at best. That said, in that repetition is a mending impulse, one that takes a broken mirror and makes it whole. All of this to reiterate that Tuki should not be misconstrued as a ceremony for our anthropological scrutiny, but taken rather an invitation to sing, to speak, to dance as we are.

Wasilewski/Kurkiewicz/Miskiewicz: TRIO (ECM 1891)

Marcin Wasilewski piano

Slawomir Kurkiewicz double-bass

Michal Miskiewicz drums

Recorded March 2004 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

there’s a beautiful view

from the top of the mountain

every morning i walk towards the edge

and throw little things off…

it’s become a habit

a way

to start the day

–Björk, “Hyperballad”

The hapless reviewer grows weary hailing each young jazz trio that comes along with something fresh as a re-invigoration of the field. But in the case of pianist Marcin Wasilewski, one would be fool not to. Along with bassist Slawomir Kurkiewicz and drummer Michal Miskiewicz, the young Pole first wowed ECM listeners backing Tomasz Stanko in such watershed recordings as Suspended Night and Lontano. For its first international disc, his self-assured trio presents a modestly titled set of original material and improvisations, plus a couple of surprises for good measure.

Let’s cut right to the surprises. Wasilewski and his cohorts offer such a beautiful take on Björk’s already beautiful “Hyperballad” that one who didn’t know any better might think it a spontaneous creation. This version captures the original’s aerial perspective by means of a slightly starker color palette, cautiously approaching the slope of catharsis. The chorus materializes only toward the end, as if it were dormant, waiting for the touch of a dream. Ranking alongside The Bad Plus’ take on Aphex Twin’s “Flim” as one of the great jazz crossovers of our time, this is one to remember. More obscure is “Roxane’s Song,” which comes from the opera King Roger by Karol Szymanowski. Devoid of words and context, it remains a seductive, nocturnal aria with frayed emotional edges.

Less surprising but equally effortless in the trio’s hands is Stanko’s “Green Sky.” Not heard since Matka Joanna, this one cradles some especially sensitive drumming and achieves a robust thematic unity. Likewise, Wayne Shorter’s “Plaza Real” turns the lights down low and warms the air with its summertime reverie. The three musicians interact ever so subtly here, filling in each other’s negative spaces with choice punctuations.

That’s just the icing. Now for the cake, which bakes up sweetly in the oven of Wasilewski’s creative mind. His tunes move like trains through black-and-white landscapes, drawing the rhythm section out from its shell and into the spotlights of “K.T.C.” and “Sister’s Song.” Both are first class examples of in-flight jazz, each with a distinct melodic sweep. Wasilewski’s wingspan is greatest here, as is the loose hi-hat of Miskiewicz, who excels in this album standout. “Shine” is another prime vehicle for the drummer and further boasts Kurkiewicz’s positive vibes. “Free-bop” is an emblematic tune for the trio’s sidewinding politics, throwing spotlight once again on the bassist, who dances his way through an invigorating solo and sets off some gorgeous popping of kernels all around.

Of the set’s freely improvised portions, “Entropy” is remarkable for its tenderness. It seems to balance its emotions on an ancient scale, itself eroding but holding true. The album’s bookends, two so-called “Trio Conversations,” are the weights in its pans. Each is a fleeting thought of brush and sparkle, lost to the river from which it was fished. May the current carry on for a long while yet.

Marilyn Crispell Trio: Storyteller (ECM 1847)

Marilyn Crispell Trio

Storyteller

Marilyn Crispell piano

Mark Helias double-bass

Paul Motian drums

Recorded February 2003 at Avatar Studios, New York

Engineer: James Farber

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Although the distinction of Marilyn Crispell’s free-flowing approach to the keyboard has been evident at least since her 1983 solo album Rhythms Hung in Undrawn Sky, her sporadic ECM tenure has shown an artist coming into her own. For Storyteller, she is joined by bassist Mark Helias (filling the formidable shoes of Gary Peacock) and drummer Paul Motian. One hesitates to call them “bandmates,” for the symbiosis between the three is such that parsing them into any hierarchy of leader and followers would upset the balance of their artistry. Motian and Helias are indeed more than a rhythm section: rather, they section rhythm into its base components, fragmenting and rebuilding in real time, like Crispell herself, to suit the needs of the tune at hand.

On the subject of tunes, the set list affords fair consideration to each musician’s pen, beginning and ending with Crispell’s contributions, and through them loosely framing the trio’s open approach. In the first moments of “Wild Rose,” as Motian’s rasp breezes through Crispell’s transcendence, and they in tandem through Helias’s pockets of air, there is a sense that what we are hearing is available only to the ears. This is, in certain terms, invisible music. Dynamics are constantly flipping and shifting, so that in “Alone” Crispell billows like a curtain in the foreground, while in “So Far, So Near” she becomes now the page across which the texts of bass and drums take form. Despite being over nine minutes long, the album’s closer passes like a windblown leaf among countless others, even so yielding unforgettable color.

Motian offers five tracks, including his classic “Flight of the Bluejay,” which in this rendition flits about with descriptive perfection. Like its namesake, it cycles between lyrical glides and punctuations of caution. “The Storyteller” is notable for its sustained arpeggios and for the archaeological precision of its composer. So, too, “The Sunflower,” a brief yet sparkling ode to photosynthesis. But the two tracks marked “Cosmology” show the trio at its interlocking best, as does “Limbo,” one of two tunes by Helias; the other being “Harmonic Line,” which is the album’s most melodic and contains the first proper solo of the set, accompanied only by drums, painting the ripples of Crispell’s pebble dropping.

In the purview of these masters, each the side to a pliant yet unbreakable triangle, the title of Motian’s “Play” is as much a noun as a verb. There is, accordingly, a stark awareness of the stage, of the performance, of the importance of every set piece and backdrop. Every gesture gives off a constellation, each star a seed for countless more. Crispell is that rare pianist who can erase a picture in the same gesture that paints it. With a single wave of her hand across the water’s surface, she resets every reflection before it can pull us in like Narcissus. She is the storyteller, recording her fleeting narratives so that listeners might forever experience of the poetry of their immediacy, if not vice versa.

Manu Katché: Playground (ECM 2016)

Manu Katché

Playground

Mathias Eick trumpet

Trygve Seim tenor and soprano saxophones

Marcin Wasilewski piano

Slawomir Kurkiewicz double-bass

Manu Katché drums

David Torn guitar on “Lo” and “Song For Her (var.)”

Recorded January 2007 at Avatar Studios, New York

Engineer: James A. Farber

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Playground is the spiritual successor to drummer Manu Katché’s auspicious ECM leader debut: Neighbourhood. Auspicious, because said debut practiced just the communal sort of sharing it preached. The lineup here replaces saxophonist Jan Garbarek with the multi-talented Trygve Seim and adds to its ranks trumpeter Mathias Eick—neither strangers to one another since their appearance on Iro Haarla’s Northbound. Rounding out the cast are two thirds of the Marcin Wasilewski Trio (bassist Slawomir Kurkiewicz and Wasilewski himself at the keys), as well as guitarist David Torn. Aside from the latter’s ambient contributions to its bookends, the album luxuriates in the all-acoustic interplay of Katché’s simple yet potent tunes.

Of those tunes, we get 11 artfully crafted gems, gradated from sunrise to sunset. From the first, there is a sort of lush Americana that pervades each smooth turn of phrase, swaying like poplars in anonymous urban landscapes—a result, perhaps, of these European jazzmen soaking in the spell of New York City, where Playground was recorded. Either way, one can hear the pulse of the city’s history in the underlying beat textures. In this regard, Wasilewski’s pianism is striking for both its sink and swim. In the album’s opener it acts as an intermediate force between Katché’s supporting brushes and Eick’s leading stare, while in “Song For Her” (and its variation, which ends the set) it enables reflective bassing, pinging like pachinko balls in slow motion. Here, as elsewhere, the horns build to the non-invasive sort of head at which Katché’s writing excels.

Tracks are designated by names that are as descriptive as they are simple. Most are relatively obvious. “Motion,” for example, moves flexibly. Noteworthy is Wasilewski, given free reign in one of the session’s strongest improvisational showings, of which there are a strategic few (others being Seim’s chromatic solo in “Inside Game” and Eick’s skyward lob in “Project 58”). Despite the groundedness of Katche’s drumming, there is always something airborne about the melodic front line, so that tracks like “So Groovy” showcase Katché’s multidirectional awareness. What distinguishes his grooves, then, is less their sense of push than of pull. Here, as in “Snapshot,” the music draws ocean waters like the moon. Whether piecing together the cymbal-happy backbone of “Clubbing” or paving the smooth runway of “Morning Joy,” Katché finds strength in his attractions to kindred spirits. They clearly take inspiration from him in kind, for by the end one feels the cycle ready to repeat for a third round.

The title of the second track, “Pieces Of Emotion,” describes it best: each fragment builds a larger mental whole, a place built on togetherness, listening, and, above all, synchronicity.

Mark Feldman: What Exit (ECM 1928)

Mark Feldman

What Exit

Mark Feldman violin

John Taylor piano

Anders Jormin double-bass

Tom Rainey drums

Recorded June 2005 at Avatar Studios, New York

Engineer: James A. Farber

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Mark Feldman belongs to that selective cadre of jazz violinists ruled by such greats as Noel Pointer and Stéphane Grappelli, all while honing a storyteller’s edge so much his own that he might one day be seen as the pioneer of a new tradition. Should that ever be the case, then the 23-minute “Arcade” which begins What Exit—Feldman’s first leader date for ECM—will certainly comprise a central chapter of his scripture. It is a quintessential statement for both album and artists in kind. One first notices the delicate tracings of drummer Tom Rainey, who throughout the album shows the spectrum of his touch. Into that soil bassist Anders Jormin presses his feet like an archaeologist about to embark on a vast improvisational survey. Only when pianist John Taylor fills those footprints with plaster does Feldman whisper into being. The band almost comes together, part by part, like some parthenogenetic steam train, coalescing from metal and gristle and steam, alighting upon a track fully formed and ready to chug. But just as the ride is about to begin, Feldman and Taylor pause to take stock of things. The latter fades for Jormin’s arco dovetailing, haunting the sub-terrain as Feldman beguiles with Bach-like arpeggios before, ever the feline, slinking into a trio with Jormin and Taylor, interjected with popping duet statements with Rainey. Such eruptive flip-flopping becomes more complex and fragmentary as the train moves forward, engaging the quartet in various combinations of resolve and dissolve. “Arcade” is therefore appropriately titled, filled as it is with spontaneous sounds, which after a while take on a cadence of their own in the interest of play.

The cerebral challenges of this behemoth introduction are rewarded by “Father Demo Square,” second of the album’s eight Feldman originals. This one more smoothly and expectedly tallies the invigoration of the violinist’s characteristic grammar. Jormin takes an early solo, swinging in the loose netting woven by Taylor and Rainey, but it is Feldman’s restless beauties that overtake the foreground, courting implosion at every turn. From foreground to underground, the memorial tune “Everafter” balances cinematic foreboding with understated grandeur. The branches of Taylor’s encroaching pianism hang ripe with fruit, their scent lingering like the double stop that ends with its swan breath. As in the later “Elegy,” Feldman cuts a bitter shadow, slaloming through his backing trio’s loosely upholstered interplay along the way.

There is, however, a brighter side to this moon. Brightest in “Ink Pin,” a rousing throwback that trades licks freely toward swift-footed unity. This brilliant track boasts the special combinatory force of Jormin and Feldman, gilding the frame from start to finish. The Brazilian flavor of “Maria Nuñes” adds spice to the night, trading strings for strands in jagged, sparkly development. The tenderness of “Cadence” tips the scales yet again toward shadow, giving way at last to the light of the title track. Between its fragile liveliness and the album’s confident serenity as a whole, there is much to absorb and re-absorb. And all from a quartet of which only ECM could dream and make reality—proof of the label’s unflagging creative spirit in pursuit of jazz perfection.

Kayhan Kalhor/Erdal Erzincan: The Wind (ECM 1981)

Kayhan Kalhor kamancheh

Erdal Erzincan baglama

Ulaş Özdemir divan baglama

Recorded November 2004 at Itü Miam Dr. Erol Üçer Studio, Istanbul

Engineer: Mustafa Kemal Öztürk

Produced by Kayhan Kalhor and Manfred Eicher

The Wind is a significant way station in the travels of kamancheh (Iranian spike fiddle) virtuoso Kayhan Kalhor and baglama (an oud-like Turkish instrument, also known as the saz) master Erdal Erzincan, who under its name are captured on record together for the first time. Ghosting them is Ulaş Özdemir, the musicologist who aided Kalhor in his search for musical material during research trips to Istanbul, and who plays the divan baglama (bass saz) almost like a tambura, stretching a droning sky across which the duo may fly.

Improvisation is of primary importance in Kalhor and Erzincan’s world of sound—so much so that the performance documented here feels like one long freeform variation, divided though it is into 12 parts.The baglama has a haunting insistence about it, which tills soil until Kalhor’s bow comes sprouting through. The latter seems at first like a trick of the ear, for its verbs conjugate by way of a most understated grammar. As it becomes more faithfully inscribed, gathering minnows and courage from every limpid pool, Kalhor’s spirit billows like parachute silk between elements, of which the album’s titular wind is but one of many. Every gust of air keeps him afloat, but also reminds us of the importance of rootedness. And all of this in the album’s first six minutes.

Part II moves in swaying patterns and, like much of what follows, practices the wisdom of restraint even at its most eruptive moments. From here, the album turns fragmentary, dialogic corners, ping-ponging motifs across a divine net according to subtler rules of play. Strum-heavy passages (Part IV) are balanced by holy unions (Part V), marking slow escalation into clouds near to bursting with melody. As territories expand, so too does the capacity for these musicians to breathe. An open circuit in search of a conductor, they unleash electrical charge from the friction of their dance. Erzincan’s fingerwork in Part X inspires Kalhor to just such a lightning bolt of expression, the overtones of which are almost deafening in their affect. Kalhor’s pizzicato action in Part XI spins a different cyclone before the bittersweetness of farewell sets us on our way.

Kalhor and Erzincan inhabit everything they play as bees inhabit a hive, wagging to invisible rhythms and joining the almighty hum that activates every soul to buzz its wings. What we have, then, is the honey.