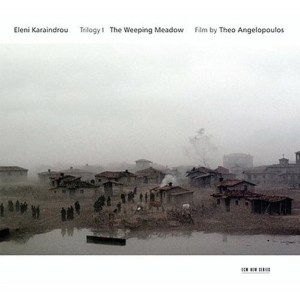

Eleni Karaindrou

The Weeping Meadow

Maria Bildea harp

Konstantinos Raptis accordion

Socratis Sinopoulos constantinople lyra

Vangelis Skouras french horn

Renato Ripo violoncello

Sergiu Nastasa violin

Angelos Repapis double-bass

String Orchestra La Camerata Athens

Eleni Karaindrou piano

Antonis Kontogeorgiou choirmaster

Recorded June 2003 at Studio Polysound, Athens

Engineer: Giorgos Karyotis

Produced by Manfred Eicher

“True sailing is dead.”

–Jim Morrison

Eleni Karainrou’s music for film is more than incidental; it is genetically enmeshed in celluloid. Melodies come to her before she sees a single frame, when migrations are still conceptual, dreamed of. This explains the rawness she elicits from Theo Angelopoulos’s swaths of mist, water, and dirt in The Weeping Meadow. “She speaks the same language that I am when making a film,” the late Greek director once said, for indeed her soundtrack is anything but paraphrase. It is as much the film as the film itself, as broad of sweep and as inward of emotion as the characters in whose skin the music resonates.

The Weeping Meadow is Part I of Angelopoulos’s uncompleted trilogy on modern Greece and spans the years 1919 through 1949. It is the portrait of a pivotal century, a coroner’s report on the body of Greece.

Behind the camera is a nation ravaged by the Bolshevik Revolution—a force of displacement that cuts the bonds of countless citizens and sets them flying into whatever currents they can catch toward safety. The Red Army’s march on Odessa looses our main characters from the rock and goads them onward.

Like the hand-colored postcards in the title sequence, their beloved city exists only as it was, frozen at the height of its opulence by the touch of memory.

Writhing on the other side of Angelopoulos’s lens is interwar America, which was for many refugees a Promised Land. People believed such things out of innocence, notes Angelopoulos in a related interview, looking as they were for a way out of their poverty. The Weeping Meadow thus unfolds as a threnody of discovery, an awakening to the mutually exclusive powers of earth and sky.

It follows the coming of age of Eleni, an orphaned foundling who falls in love with her adoptive brother Alexis, with whom she elopes after marrying his widowed father, Spyros. In the years leading up to World War II, Alexis goes to America to pursue his dreams of becoming a renowned musician, leaving Eleni to wash her tired, solemn feet in the basin of fascist repression.

As is de rigueur in Angelopoulos’s cinema, the way he tells his stories is just as significant as the stories themselves. This is nowhere truer than in the soundtrack.

What Karaindrou has done is to treat the film’s events as births and nurture them into being. Thus animated, they take on new flesh and politics. In this regard, the titular main theme is among the most representative of all she has written. Its seesawing melodies and river-run exposition move like the eternal dance that is her spirit. In the accordion we can hear Alexis’s aspirations, can feel a lure that stretches across the Atlantic and into the heart of his as-yet-unrequited passage.

“Theme of the uprooting” shines harp with cello through a prism of deeper hue. It is one of many intimate pairings throughout the program, each an expression of Eleni and Alexis splashed across the atlas of time to which they are ever subordinate.

This sensation of helplessness turns visceral through the voiceover, which marks what we are about to see as choreography on a vast stage. “Scene 1,” the voice begins, establishing a self-aware, non-diegetic world in which we are but fleeting, curious spectators. Along the banks of Thessaloniki—“a wound that will not heal”—a mass of humanity approaches, torn yet regardful. Life as they once knew it is gone, as threadbare and uncertain as they are.

“Waiting” holds true to this tension, wrapping its wings around Eleni’s unfathomable resolve, which liquefies in her arrest. As water drips from her hands like tears (an image that recurs in the trilogy’s second part, The Dust of Time), she becomes life itself, percolating through crack of stone and pocket of soil into the earth’s molten core.

Eleni’s twin soul resides in “The tree,” another recurring melody that stands as the only reminder of community. Its lachrymose branches have shed their leaves long ago. In their place are strains of accordion, piano, and lyra…fish swimming in murky waters. The single tree is a living cipher, a leitmotif akin to the sapling in Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice. Although more often looming in the distance of the refugees’ makeshift settlement…

…up close it is ornamented with animal carcasses: not an omen of what will be, but of what might have been.

When the settlement is flooded and puts those nomadic hearts back on the line, it weeps in their absence. For as democracy commits suicide all around them, its roots are the only ones left.

“Young man’s theme” is another of the soundtrack’s more character-driven pieces. Its interlocking circles of accordion, lyra, and harp weave a thinly veiled portrait of the film’s love triangle, which like an all-seeing eye penetrates the viewer in return. That gaze is as prolific as it is omnipresent. From the long pan over riverbanks worn by wheel of cart and sole of shoe to the silent epidemic that offers Alexis’s mother to the talons of a bird of deathly shade, it watches until things drown. It reminds us that Alexis has already wounded Eleni with a family she can never have (when we encounter her as a teenager her twin boys, born in secret, have already been adopted out). Upon her return, Alexis goes to Eleni in the night and asks her, “Remember when we used to say we’d follow the river to the find the source?” He is too young to realize that Eleni has been that source all along. Although they have shared a moment through the window, separated by songs of men, being together means that some form of shattering is inevitable.

That each of the above themes has its variations reminds us that constellations are never fixed. They are the changing of the guard from day into dusk, an enigmatic realization of that unflagging gaze. All of which makes the standalone pieces glow with their potency of message.

Anchored by a violin solo that invokes Karaindrou’s theme for Ulysses’ Gaze, “Memories” caresses the garments of a loved one who has passed. Here we find pause and reflection for the wayfaring mind. The quiet tide of strings barely touches the shore before an emotional sponge dabs it away as if it were but a tear on the face of an immeasurable deity.

“On the road” spins an even more reflective pathos, its wheels turning in search of traction and finding it only the choir of “Prayer.” Therein lies the film’s most abrasive benediction. It weeps neither for itself nor for us, but for those who do not know, those we can never know, those without name in places without time. It encompasses Eleni’s resilience tenfold: her spying on the twin boys, drawn into a web at conservatory; her flight with Alexis into the shelter of a sympathetic theater troupe, and Spyros’s vengeful shame at knowing his pride is lost; the final dance before Spyros collapses, never to breathe again; his watery pyre, floating somewhere between the fantasy he could never endure and the reality that substitutes his existence with sticks and decay.

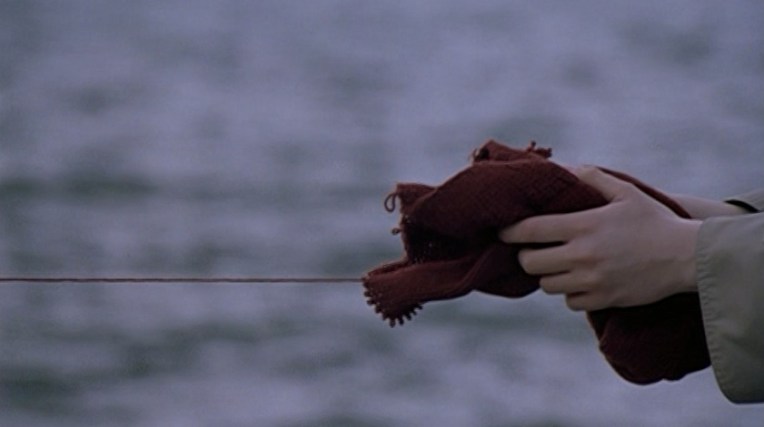

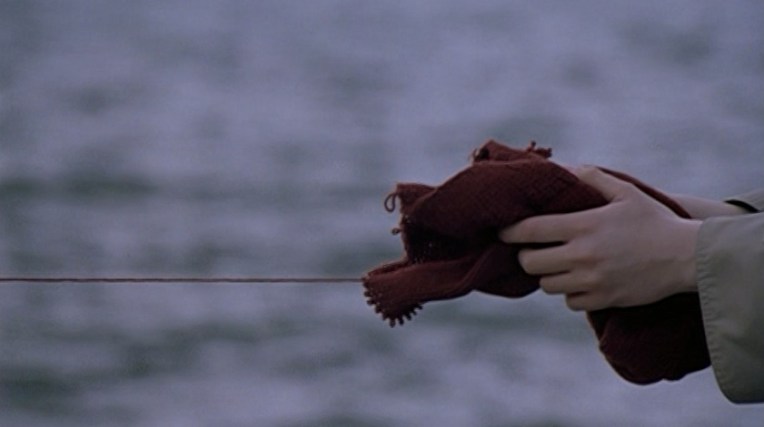

Simply calling Karaindrou’s sound-world “cinematic” is as misguided as calling the sky blue, for it too fades to black when the day is over. Despite its fictional ties, its shapes are as real as the musicians who bring it to life. It is, rather, an amorphous body of tears and gestures, the departing ship that pulls Alexis and Eleni apart.

A red thread is all that connects, the unraveling of an unfinished garment.

After it falls into the ocean, and with it the promise of balance, Eleni returns to the old house, ruined, in the water.

Its voices have washed away. Eleni has been washed away. Everything has been washed away.

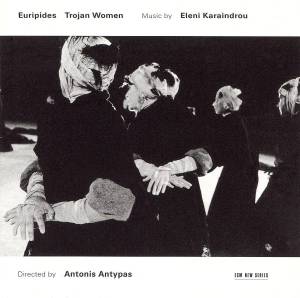

Alternate covers: