This INDEX anthology of queer, transgressive, and body-centered performance is a study of resistance in motion, shaped by Dietmar Schwärzler’s observation that, despite their aversion to gender fluidity, post-socialist societies are increasingly unable to suppress it. The selections curated here orbit one another like unstable particles, abrasive and intimate, each refusing the comforts of binary thinking. What forms is a constellation pushing against regulation and decorum, insisting that desire, embarrassment, violence, humor, and play be allowed to exist without being pressed back into polite accounts. It yields a portrait of a Europe whose margins speak more urgently than its institutions, where artists carve through rigid traditions with the unsharpened saw of selfhood.

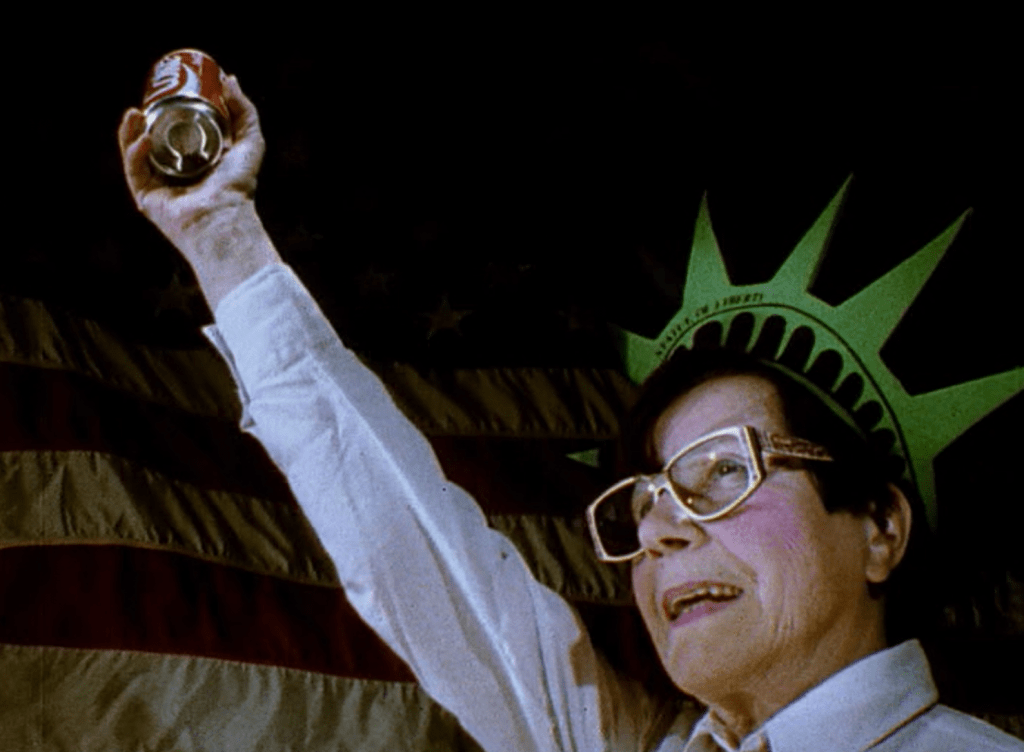

This insistence on subjectivity announces itself from the beginning in John Giorno and Antonello Faretta’s Just say no to family values (2006), which stages an ecstatic performance in a tiny southern Italian village built to repel the unfamiliar. An elderly woman quietly observes Giorno as he recites his poem of the same name, a text that celebrates drugs as sacred substances and mocks Christian fundamentalism as a cultural virus, his voice ringing against the village’s stone surfaces. Giorno’s sentiments land gently in the air and harshly in the psyche.

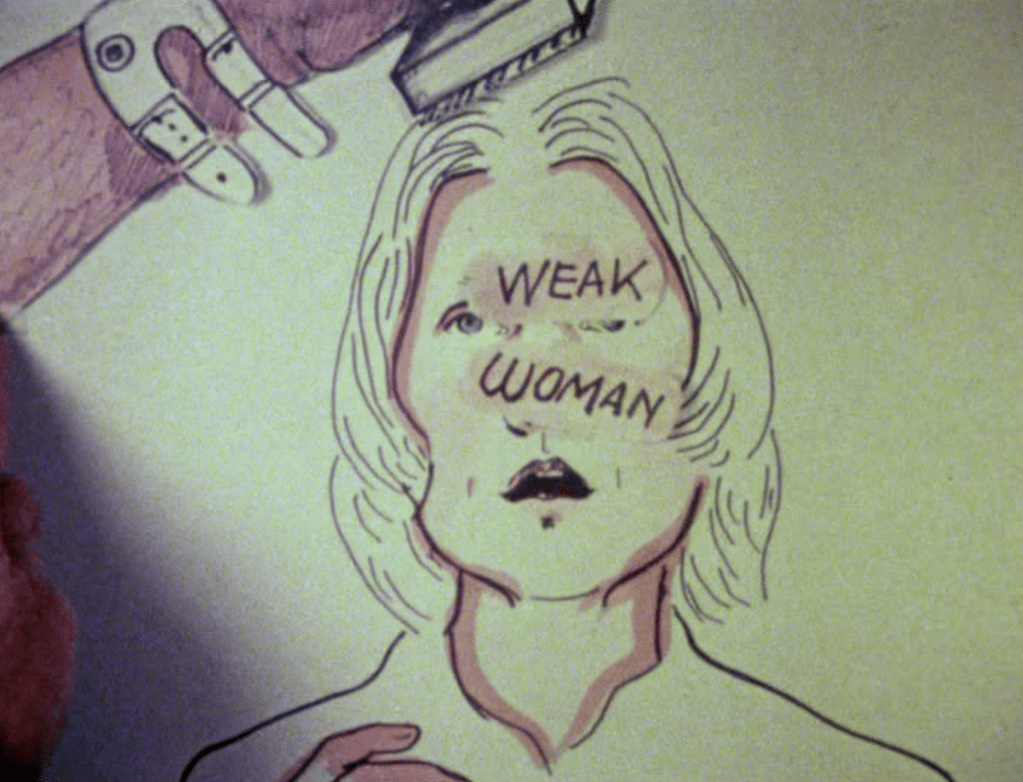

Keren Cytter’s Der Spiegel (2007) elicits an even deeper tension. A 42-year-old woman sees herself as 16 because that is the age she imagines as desirable to the man she wants, a man who hardly deserves the labor of self-distortion. Mirrors open into recursive realities. Bodies multiply. Voices contradict themselves as if consciousness were rewriting its script in real time. A Greek chorus of women comments from outside the frame while the man who enters seems split between presence and condescension. Cytter reveals the violence that occurs when desire is shaped by misogyny: the self becomes a repertoire of poses rehearsed for someone else’s gaze until the poses crumble.

The body continues its revolt through the tangle of breath, fabric, and friction that is Maria Petschnig’s KIP MASKER (2007). Clothing is now a prosthesis, a means of making the body unrecognizable to those who would read it through convention. The soundtrack is raw: scraping threads, stretched seams, the sound of breath negotiating constraint. What emerges is an exploration of femininity stripped of its expected ornamentation, a choreography in which awkwardness becomes a form of liberation and confidence grows through estrangement.

Patrycja German’s Schenkeldrücken (Leg Wrestling, 2005) translates such interior struggles into a public contest. When the filmmaker challenges a group of men in Kraków to a leg wrestling match, they laugh at first, using humor to conceal their discomfort as they lose again and again. Her force remains steady, revealing the fragility of masculine assurance and the potency of female strength when staged without theatrics.

The anthology shifts into darker territory with Jaan Toomik, Jaan Paavle, and Risto Laius’s Invisible Pearls (2004), a descent into prison masculinities where desire, violence, and survival become inseparable. Men speak in fragments about coercion, self-enhancement, and mutilation in a disturbing film that reveals how sexuality mutates under duress, the body now the only site where agency can be claimed or lost.

Karol Radziszewski’s Fag Fighters: Prologue (2007) imagines milder forms of insurgency through craft turned militancy. An elderly woman knits pink yarn, which feeds into a machine that produces a vivid scarf, which in turn serves as the material for a ski mask. The mask is a tool for queer resistance, equal parts protection and provocation. Thus, domestic labor is reclaimed as an armament for a fantasy army that refuses invisibility.

If resistance often requires reinvention, it can also require drift, as in Deborah Schamoni’s Dead devils death bar (2008). In what Ken Pratt calls a Fassbinder-influenced satire of Berlin’s Bohemian nightlife, the single tracking shot features actors rotating through personas, conversations that collapse into absurdity, and an atmosphere thick with posturing. Nothing anchors these characters except their own shapeshifting roles. Even so, the emptiness of their talk becomes revealing. Behind the curated surfaces lies the weariness of souls trying to invent themselves with too little material.

The bonuses extend the anthology’s tonal range. Paolo Mezzacapo de Cenzo’s Under Water (1971) moves through a dreamlike forest of erotic projections set to Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht. A man’s fantasies spill across scenes populated by multiple women, a baby, and a vague sense of guilt. Less a story than a psychic event, it is a veritable murder mystery conducted inside the self. John Giorno’s poem is also included as a PDF, revealing the sculptural precision behind his spoken word and reminding us that incitement can be both spiritual and surgical.

Across the entire collection, what emerges is not a stable argument but a terrain of embodied freedom. These films resist the false security that binary identities pretend to offer. They express different tactics of survival through erotic distortion, militant softness, and the refusal to quiet the thinking of the flesh. Together they form an archive of renegotiations, insisting that individuality is a continual act of becoming. And so, the most radical gesture remains the simplest: to let love explode on its own terms.