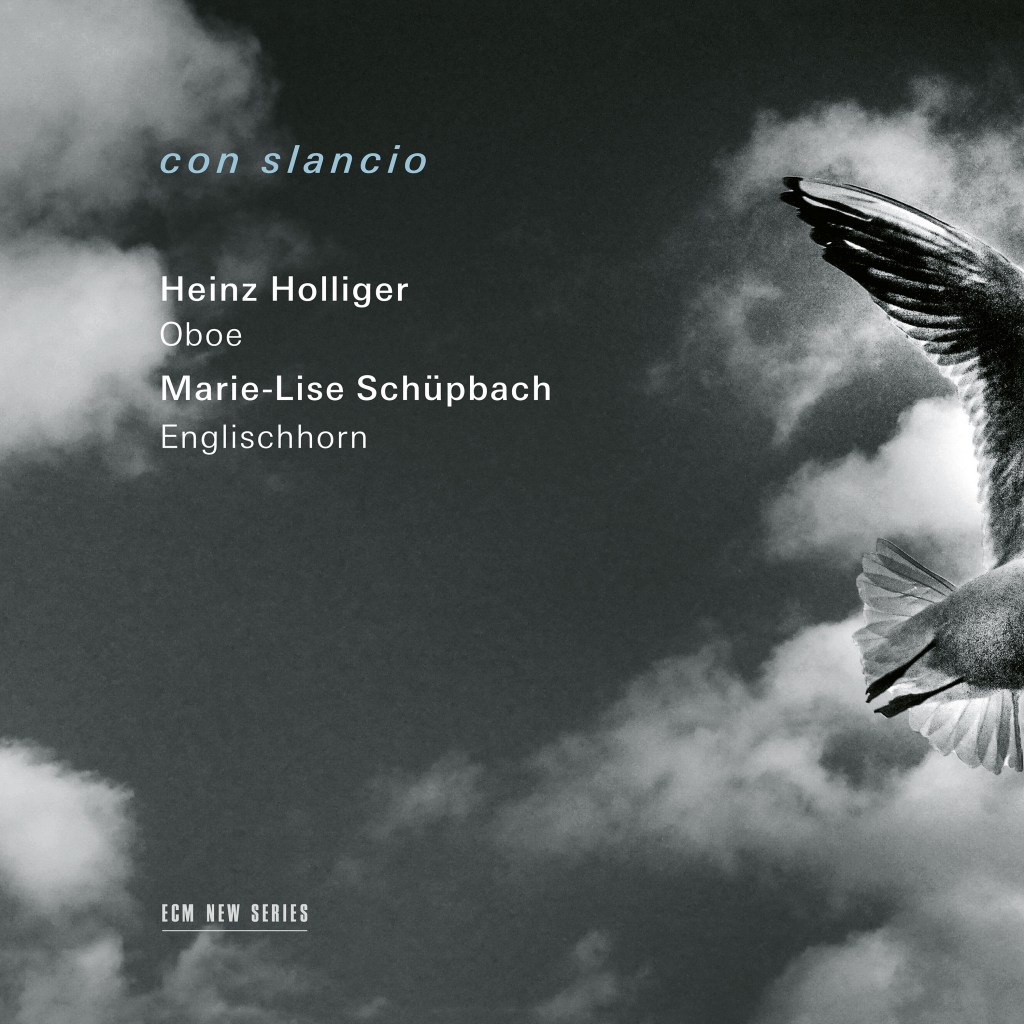

Heinz Holliger

Marie-Lise Schüpbach

con slancio

Heinz Holliger oboe, English horn, Sprechstimme

Marie-Lise Schüpbach English horn, oboe

Recorded July/August 2020

Radiostudio DRS Zürich

Engineer: Andreas Werner

Cover photo: Jean-Marc Dellac

An ECM Production

Release date: February 6, 2026

“I don’t want to communicate something definite, something concrete. I find music entirely unsuited for that.”

–Heinz Holliger

This latest recording for ECM New Series by Heinz Holliger and Marie-Lise Schüpbach, who last appeared together on 2019’s Zwiegespräche, feels less like a recital than an extended meditation on the tremor that precedes orality. Across its span, the oboe becomes a site where language approaches, falters, and reconstitutes itself. Holliger’s return to composing for the instrument after decades of reticence gives the album its emotional and philosophical axis. In the booklet interview with Michael Kunkel, he speaks of Klangrede, a kind of sonic declamation in which music thinks aloud without becoming discourse. Rhythm for him is not a law but a mood. “Only in strict moments do I use a rigid framework,” he admits, “otherwise, I simply can’t bear it.” One hears in this a deeper suspicion of any language that hardens into doctrine. Music, he insists, is abused when reduced to a message. There is no lesson here, only a soul seeking its acoustical climate. With the oboe, that climate is paradoxical, what he calls “speaking with a closed mouth.” The entire program plays with this idea, as if testing how much meaning can survive in the face of a written score.

Holliger’s own con slancio from 2018 opens the project like a gasp before a sentence. Played by him alone, it begins with a leaping gesture that keeps missing its metrical footing. Fluttering figures scatter upward into brief star-flecks of multiphonics before dissolving into a luminous fade. Rather than announcing a theme, the piece performs hesitation itself. This sense of suspended utterance returns in his Ständchen für Rosemarie, where the English horn spars with its own desire to communicate, turning inward midway to reveal dreams that feel both candid and concealed. The two duo pieces from 2019, Spiegel – LIED and LIED mit Gegenüber (contr’air), place melody inside a hall of distorting mirrors. In the first, microtonal inflections make each phrase mishear itself, whereas the second builds nested dialogues in which the instruments appear to listen to their own thoughts while voicing them. The later works Fangis (fang mich) and à deux – Adieu, both from 2020, entwine play and specter, quick verbal-like exchanges interrupted by haunted multiphonics that sound like syllables losing their jobs.

Around these pieces gathers a constellation of works written for Holliger over decades, each treating the oboe as a dialect in danger of dissolving. Toshio Hosokawa’s Musubi from 2019, for oboe and English horn, knots the two players together only to let them unravel again. The instruments align in heart yet retain separate bodies, inventing a private grammar of crane-like calls that shed purpose precisely by insisting on it. As articulation softens, the music sinks into a subliminal murmuring. Jürg Wyttenbach’s Sonate für Oboe solo from 1961 is an entire idiom compressed into four movements. The opening juxtaposes public proclamation with whispered aside, while the second turns inward like a language translating itself into secrecy. The third becomes a virtuosic thicket in which Holliger’s upper register fractures into glittering particles before the epilogue lets the instrument split its tongue into a dance that evaporates into silence.

Jacques Wildberger’s Rondeau für Oboe solo from 1962 begins with disarming lightness, a kind of conversational sparkle that slowly acquires gravity. Higher registers awaken like excited vowels, yet beneath them lingers the anxiety that too much thought can make flight impossible. György Kurtág’s con slancio, largamente from 2019, played on English horn, answers this with austere brevity. An opening octave plunges downward into the instrument’s dark interior, brushing past a fleeting memory of Bach before collapsing into aphorism, and aphorism into an empty shell. Rudolf Kelterborn’s Duett für Oboe und Englischhorn from 2017 initially speaks in whispers but soon weaves an intricate web of gestures, a conversation that proves restraint can be the most baroque form of eloquence.

Finally, Robert Suter’s Oh Boe für Oboe solo from 1999 becomes the album’s most openly linguistic experiment. Holliger adds Sprechstimme for this recording, a personal gloss absent from the score. The spoken fragments stumble between playfulness and severity, nonsense and revelation, as if caught in a productive net of aphasia. Directions trip, recombine, and disintegrate, scattering meaning across the floor for the listener to collect, knowing that some syllables will forever be missing.

Taken together, these pieces create a cartography of inaudibility. Breath functions as syntax, timbre as grammar, silence as punctuation. The oboe emerges not merely as an instrument but as a fragile throat, perpetually on the brink of forgetting how to talk and therefore speaking all the more urgently. Music here does not replace language, nor does language dominate music. Instead, both hover in a trembling middle space where saying and sounding keep mistranslating each other.

By the album’s close, one senses that meaning survives only by remaining porous. Every phrase feels as though it might dissolve before finishing itself, and that very instability is what keeps it alive. Speech does not end in sound, sound does not end in speech. They circle one another like letters afraid of becoming words.