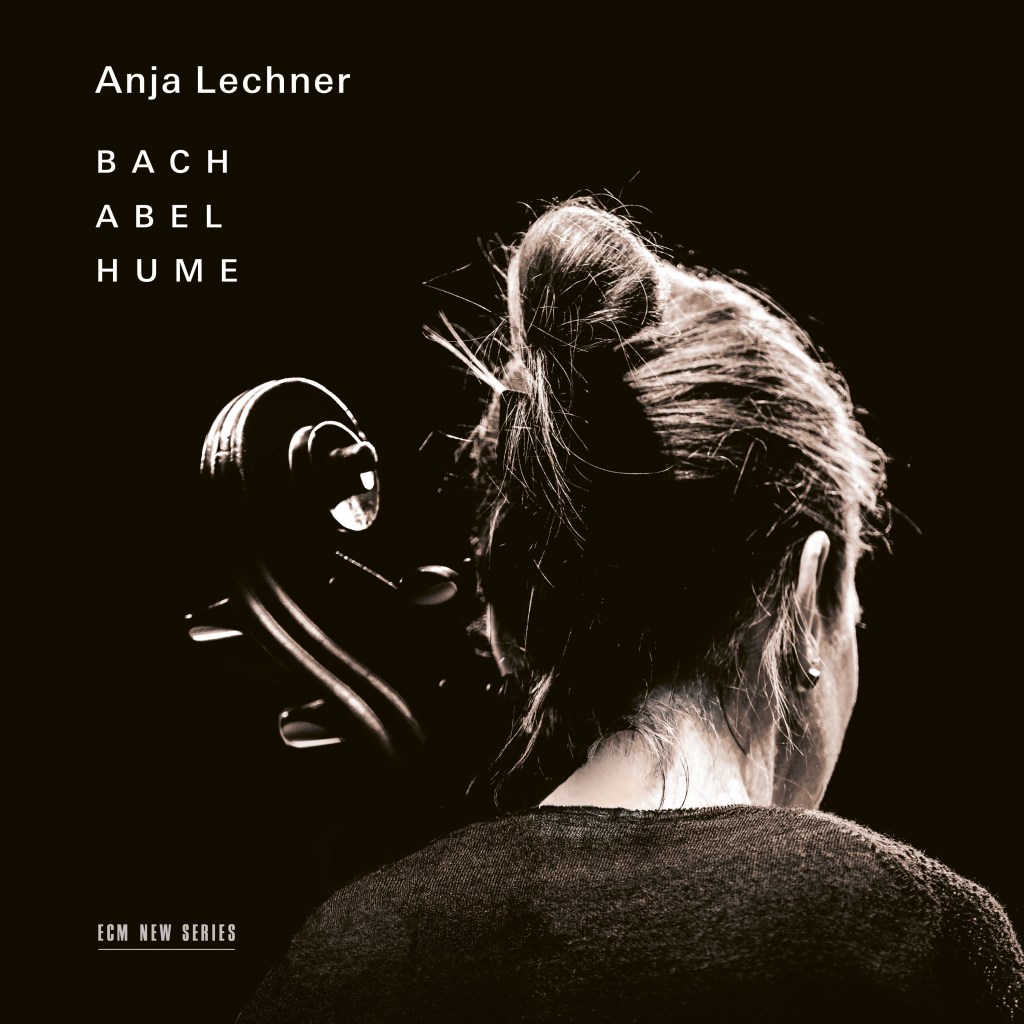

Anja Lechner

BACH/ABEL/HUME

Anja Lechner violoncello

Recorded May 2023, Himmelfahrtskirche, Munich

Engineer: Peter Laenger

Cover photo: Sam Harfouche

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: October 18, 2024

A solo program is never a solitary endeavor. While it may nominally include a lone performer—in this case, cellist Anja Lechner, in her first such recording—it is ultimately a conversation with the music, engineer, producer, and oneself. And in the trifecta of composers assembled here, we are included in that conversation. Throughout the opening swoon of A Question, one among a handful from former Scottish mercenary Tobias Hume (c. 1579-1645), and its companion piece, An Answer, the beginning and the ending become indistinguishable. (I also like to think that the answer comes unintentionally in the snatch of bird song heard at the end of the latter track.) Harke, Harke features pizzicato colorations and bow tapping—and may, in fact, be the first score to feature a col legno instruction—for delectable contrast. These pieces are from Hume’s 1605 collection of dances and miniatures, “The First Part of Ayres,” welcoming us into a sound-world that begs uninterrupted listening.

German pre-Classicalist Carl Friedrich Abel (1723-1787), another viol master who returned to the form a century and a half later, yields two vignettes in d minor. Where his Arpeggio is an enchantment, shining across the strings in refracted sunrise, the Adagio is a piece of paper blown down a cobbled street by the wind of an oncoming storm.

Against this backdrop, the Cello Suite No. 1 of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) is a piece of a fallen star. In the Prélude, there is enough shadow to remind us that even the most joyful discoveries depend on sorrows, rendering their contours all the more pleasurable to behold. Lechner wields her bow as the weaver does a shuttle. From where she sits, the frays of the tapestry’s backside are within reach, while from our perspective, it is richly and coherently patterned. As the Allemande shapes the clouds and sky, the Courante and Sarabande populate the valley below with equal measures of vibrance and infirmity. In the Menuet, we encounter the tinge of old age, where eyes still sparkle with the naivety of youth even as they are tempered by the cataracts of regret. The final Gigue frees the soul from its cage.

Given how heartfully Lechner renders all of this, moment by precious moment, how can one not reflect upon her spirit of exploration and improvisation through a career as varied as her repertoire? We are all the more blessed by her ability to pull life from her instrument as one draws water from a well. Like the composer himself, even when repeating the same format in the Cello Suite No. 2, she holds the power of variation incarnate. This Prélude is a drop of ink preserved in water, holding its color and identity no matter how much the Allemande may jostle it. Lechner maintains a level voice, holding firm to the horizon so that the occasional flight toward the sun or dive toward the ocean floor feels all the more novel. In that sense, the Courante is as vivacious as the Sarabande is funereal, each a stage setter for the final footwork.

Further aphorisms from Hume, each addressing a different facet of the human condition, conclude the recital. By turns playful and sensual, they delight with such titles as Hit It In The Middle and Touch Me Lightly. The strongest musculature is reserved for A Polish Ayre, which reminds us of just how physical the cello can be. Throughout these interpretations, Lechner is ever the shaft of light to its prism, splitting a spectrum of mastery that can only flourish behind closed eyes. The result is an act of great intimacy built over years of trust with ECM and its listeners, giving her soil to plant a variegated garden of nourishment. She has the dirt under her nails to prove it. Let the water of our high regard be its rain.