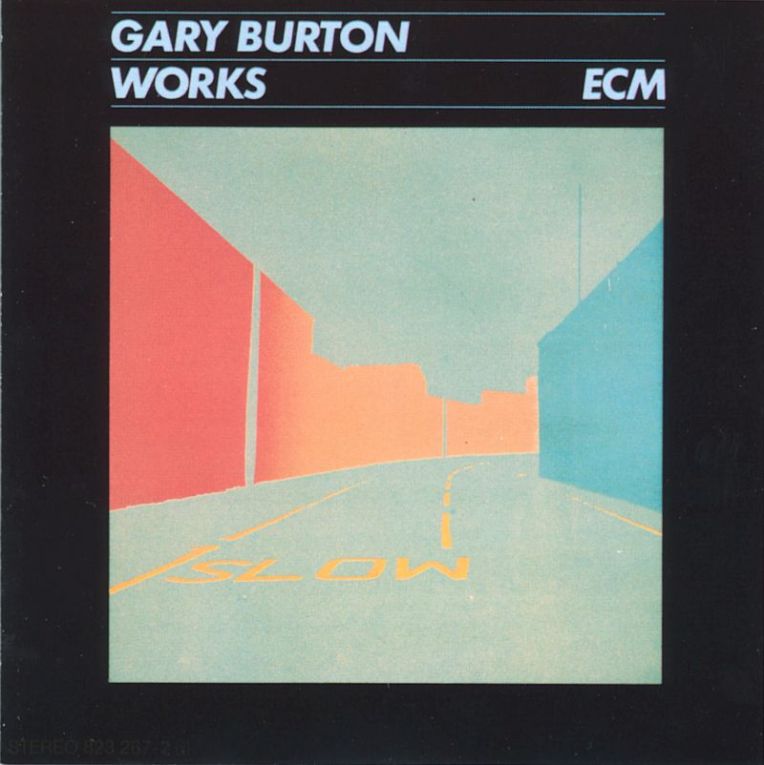

Gary Burton

Works

Release date: April 1, 1984

Vibraphonist Gary Burton, one of the defining voices of ECM’s formative years, is worthily honored in this second “Works” series installment. His contributions as virtuoso and interpreter of the instrument are unparalleled, and on ECM both aspects of his career found ample space in which to flourish. This particular era of the 1970s, which followed his RCA blitz, showed him also to be a musician of great patience, as on The New Quartet. The 1973 classic dropped him into a studio with guitarist Mick Goodrick, bassist Abraham Laboriel, and drummer Harry Blazer for a set as gorgeously played as it was conceived. From it we are treated to Keith Jarrett’s “Coral,” of which every spindly leaf is accounted for, and Carla Bley’s “Olhos De Gato,” which waters a groove that is laid back but never subdued. Those chamber sensibilities give way to more luscious details in “Vox Humana,” another Bley tune that references 1976’s quintet outing, Dreams So Real.

While Burton was quick to expound at length on any given theme, he also gave his bandmates room to breathe. This was especially true of 1974’s Ring, for which the quintet was augmented by bassist Eberhard Weber. From that album we are afforded “Tunnel Of Love.” Burton’s pitch-bending adds a degree of physicality to this nostalgic slice of life by Michael Gibbs. The third of 1974’s Seven Songs For Quartet And Chamber Orchestra is another master class in delayed gratification and defers to the bassing of Steve Swallow.

The remainder of this compilation features the deeper integrations of Burton’s duo projects. His highest achievement in this regard, 1973’s Crystal Silence, pairs him with pianist Chick Corea. The track chosen to represent it, “Desert Air,” is a springboard for some of the most virtuosic finishing of sentences one is likely to encounter in such a collaboration. Another duo project with Ralph Towner, 1975’s Matchbook, yields the title track, in which percussive impulses from the guitarist clear the road for an unimpeded ride over flatlands. And on “Chelsea Bells” and “Domino Biscuit” (Hotel Hello, 1975), both by Swallow, the composer joins Burton on piano with touches both anthemic and gospel-esque. All of which leaves us with an abridged version of an oeuvre steeped in timeless energy. A gift that keeps on giving, decades later.