I’ve reviewed Schönbrunn, the leader debut of pianist Yuri Storione, for All About Jazz. An altogether uplifting piano trio album from a phenomenal young talent. Click the cover to read on…

Non-ECM Reviews

Marcello Pellitteri review for All About Jazz

Kata review for RootsWorld

Fred Hersch review for The NYC Jazz Record

An intimate portrait of a pianist and composer at the height of his career, produced and directed by Charlotte Lagarde and Carrie Lozano, this documentary polishes facets of Hersch’s life that may be less obvious to casual fans. Viewers are introduced to Hersch as he descends the stairs of New York’s Jazz Standard to set up for a performance. From a web of starts, stops and stolen glances, the sound of a musician who now stands among the giants of jazz piano takes shape.

In the words of music critic David Hadju, one of a handful of advocates interviewed, “Fred’s music is borderless” and the film shows that characterization extending further to his personality. As one who embodies the art of improvisation outside the cage of performance, Hersch is invested in the outcomes of jazz beyond boundaries. It’s there in his organic mosaic of traditions and influences, in his willingness to work with a variety of musicians and in his activism as an HIV-positive gay man. The latter point, largely yet respectfully stressed throughout, is vital to understanding his music’s river-like qualities, which constitute nothing less than an ode-in-progress to life itself.

Nowhere is this so boldly expressed than in his My Coma Dreams, the preparations for and premiere of which dominate this documentary’s second half. Inspired by a series of vivid dreams Hersch experienced after an infection forced him into a coma in 2008, this multimedia work employs speech, video projection and live musicians to tell the story of his recovery. As pianist Jason Moran points out, however, more important than Hersch’s brush with death are the ways in which this magnum opus underscores his historical importance as a torchbearer of jazz’ reckoning with hardship. It’s a message underscored by his biography, which the filmmakers uncover through interviews with his mother Florette Hoffheimer and partner Scott Morgan, but also by his tireless mission to treat music as reality over fantasy. Hersch is keen on acknowledging the specificity of any given performance as an event and hopes that listeners may do the same in return.

((This article originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of The New York City Jazz Record, of which a full PDF is available here.)

ETHEL review for RootsWorld

Ove Johansson review for The NYC Jazz Record

On Christmas Eve, 2015, Swedish jazz lost an undisputed maverick in Ove Johansson. All the more fitting then that the tenor saxophonist’s swan song should span seven discs in as many hours. Although just as comfortable tying his laces on straight as he was yanking them off his shoes and throwing them in the listener’s face, over the years Johansson settled into a trademark solo style, marrying long-form improvisations with electronics. While on paper this may recall John Surman’s classic reed-and-synthesizer experiments of the 80s, in practice Johansson’s is a less cohesive art. Which is not to say it doesn’t bond in accordance with its own clandestine rules. For while the electronics—which range from drum machine beats to impressionistic waves—at first seem like a cheap application of retrospective blush, over time their dated quality reflects these danses macabre with clarity. Still, seven hours of such clarity will test your resolve, if only because Johansson’s playing is so engaging on its own that anything added to it feels secondary at best and, at worst, intrusive.

The first four discs, along with the last, consist of hour-long improvisational treks over amorphous landscapes. Each is named after a month, November and December being the synth-heaviest and most meandering of the bunch. Discs five and six, which together boast 45 tracks, are the most exciting, spotlighting Johansson as they do in live settings. The compactness of these pieces makes them visceral, so that one can almost smell the sweat of their kinesis. All of this feeds into the seventh disc, which reveals the album’s sharpest edges and rewards the journey with rawness.

Just as Johansson was a self-taught musician, so too does his music require self-taught listening. There’s no roadmap or manual: just a splattered terrain that begs the tread of an adventurous ear. Listening to this set is like breaking a hermetic seal, out of which come spilling years of pent-up energy, which in light of his death reads like messages from the other side.

(This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of The New York City Jazz Record, of which a full PDF is available here.)

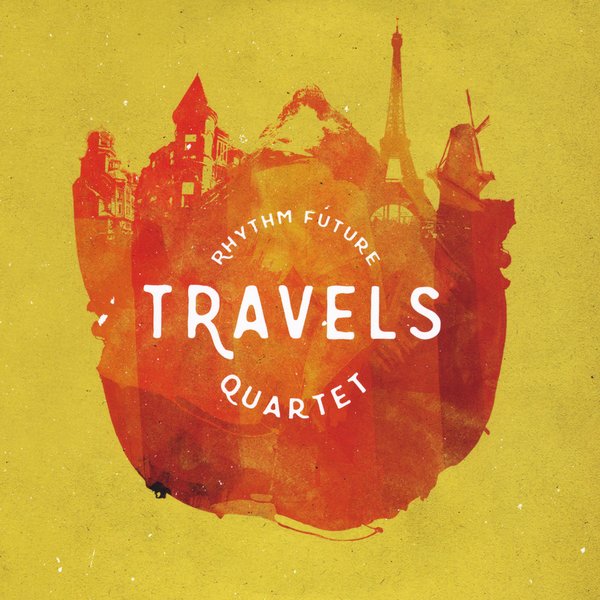

Rhythm Future Quartet: Travels

The Rhythm Future Quartet—composed of virtuosos Jason Anick on violin, Olli Soikkeli and Max O’Rourke on guitars, and Greg Loughman on bass—extends beyond its Django Reinhardt roots for a sophomore, but in no way sophomoric, set of mostly original compositions.

With five tunes to his name, Anick boasts the lion’s share of thematic credit. His writing has a distinctive tenderness about it and, like his playing, shines with confidence. Whether evoking fond memories in “Still Winter” and “Amsterdam” or exploring more upbeat romanticism in “Vessela” and “The Keeper,” he moves through every luscious key change like the sun through shifting clouds. In the title track especially, co-written with O’Rourke, he rewards patience with prettiness, but always with an integrity that recalls the hybrid textures of Nigel Kennedy’s collaboration with the Kroke Band. O’Rourke’s fretwork dazzles further in his own “Round Hill,” which to my ears sings of the sea.

Soikkeli pens two tracks of complementary temperament. “For Paulus” develops unforcedly, epitomizing the band’s penchant for letting the music breathe. “Bushwick Stomp,” on the other hand, swings right out of the box, stowing us away aboard a night train to Munich. In both, the composer’s exchanges with Anick are more than worth the risk of being caught. Loughman counters with his own “Iberian Sunrise,” opening the album in utter loveliness. Cool currents of air waft through the guitars, caressing a dancing violin. The precision is immediate and strong, hitting the ear like a nostalgic fragrance would the nose.

Rounding out the set are a trio of French tunes, including the muscular “Je Suis Seul Ce Soir” by Paul Durand, and a fresh take on John Lennon’s “Come Together” for good measure. All of which makes for a colorful palette to which you’ll want to return your listening brush in enjoyment of new hues. The band coheres so organically that one cannot imagine this group or its music being performed any other way. It’s an approach that feels just as ironclad as your enjoyment of it.