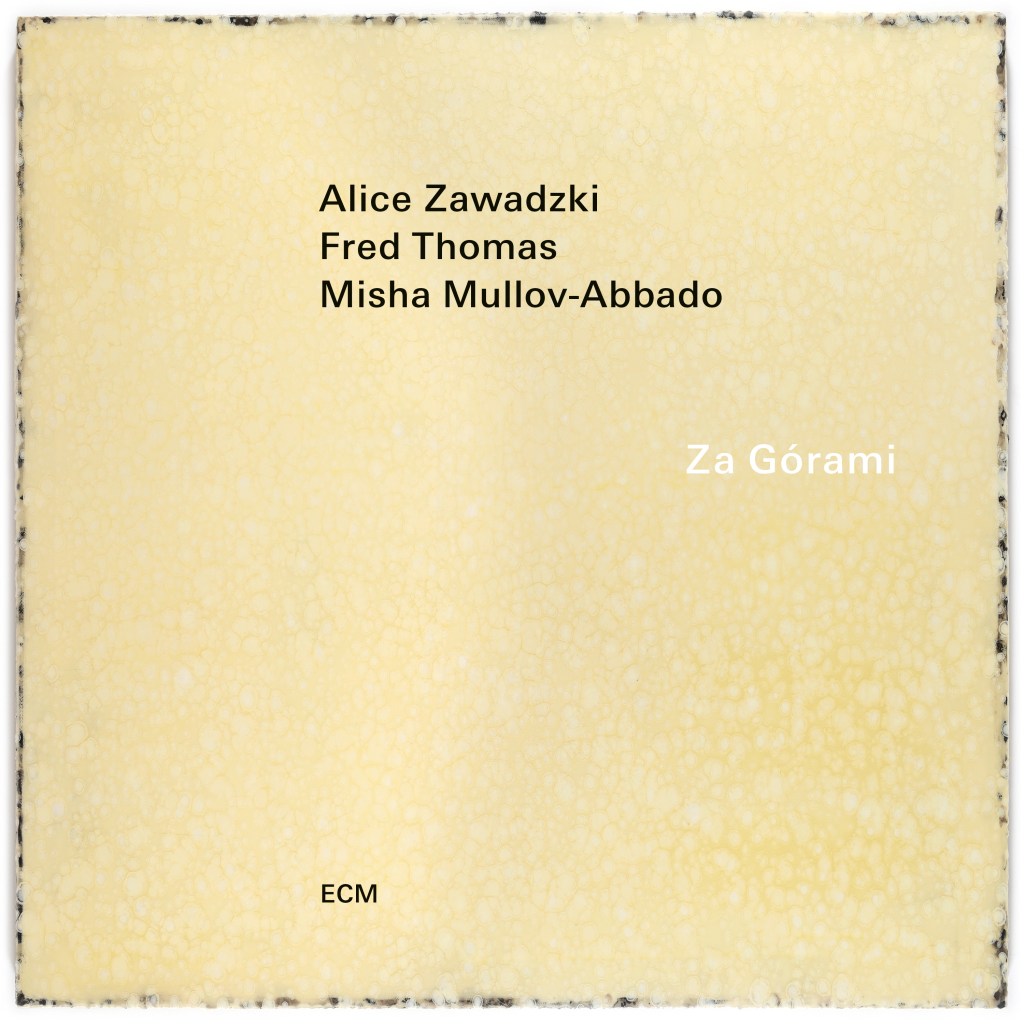

Alice Zawadzki

Fred Thomas

Misha Mullov-Abbado

Za Górami

Alice Zawadzki voice, violin

Fred Thomas piano, vielle, drums

Misha Mullov-Abbado double bass

Recorded June 2023 at Auditorio Stelio Molo RSI, Lugano

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Cover painting: Emmanuel Barcilon

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: September 13, 2024

Collected on our travels and taught to us by our friends, these are songs we have learnt and loved together. Gathered from Argentina, France, Venezuela, Poland, and the deep well of Sephardic culture, these folk tales speak to the moon, the mountains, the rain, the madness of humans, and the prophecies of birds.

The above is more than a collective artist statement from Alice Zawadzki (voice, violin), Fred Thomas (piano, vielle, drums), and Misha Mullov-Abbado (double bass). It’s also an example of how traditions, regardless of geographical distance, are organs of a larger body. Said body is literal, not metaphorical, insofar as it connects all of humanity at the internal level (the blood), even when the external (the voice) seems so disparate. The album’s title, Za Górami, says the same. Although it translates to “Behind the Mountains,” it is the Polish idiomatic equivalent of “Once upon a time…,” less a prompting of place than of possibility—not unlike the selections gathered here.

Within the trio’s curation of material, there is a liberal sprinkling of Sephardic songs. And yet, while some of the most well-worn treasures of the repertoire, including “Los Bilbilikos” (The Nightingales) and the lullaby, “Nani Nani,” are to be expected, the tact of each arrangement is remarkable. Even when the latter builds to an almost rapturous conclusion, it never loses sight of slumber’s healing effect. Such restraint is only made possible by a receding musicianship that lets the verses speak for themselves. This is increasingly rare to hear in Ladino programs, which can feel over-arranged as early music ensembles seek to outdo one another, favoring the interpreters over the interpreted. Not so in the hands of Zawadzki, who pours vocal plaster into “Dezile A Mi Amor” (Tell My Love) and “Arvoles Lloran Por Lluvias” (The Trees Weep For Rain) as if they were footprints in a landscape to be disturbed as little as possible. The tone and shape she brings to even wordless improvisations constitute natural delineations of their source material.

In Gustavo Santaolalla’s “Suéltate Las Cintas” (Untie The Ribbons), we find a most suitable modern companion. Steeped in the composer’s characteristically cinematic qualities, it lends itself to broader strokes in an instrumental economy. Thomas’s pianism is a warm evening breeze that equalizes the ambient air of its chamber and the lovers breathing it in. Its denouement alongside Mullov-Abbado’s heartbeat weaves a veil of privacy before Zawadzki renders their ecstasy a poetic afterimage. Another kindred spirit awaits in “Tonada De Luna Llena” (Song Of The Full Moon) by Venezuelan singer Simón Díaz, which yields some of the most evocative descriptions:

I saw a black heron

Fighting with the river

That’s how your heart

Falls in love with mine

The moon, even when not explicitly mentioned, is a constant presence in these songs, shining on the maiden in “Je Suis Trop Jeunette” (I’m Too Young, after Nicolas Gombert) who dreams of being swept away from her family. Her internal conflict is only heightened by the prepared piano in the upper registers, which carries over into the title song by Zawadzki, after the Polish traditional about a girl who defies her mother and ends up dancing her life away. “Gentle Lady,” Thomas’s setting of James Joyce, is a folk song in and of itself, stepping out of time to unravel its literary knot with grace.

ECM listeners familiar with the label projects of Savina Yannatou, Arianna Savall, and Amina Alaoui will feel swathed in comfort here, even as they are caught up in the unique flow that only this trio can bring forth from the hillsides of their wanderings. How fortunate we are that their paths have aligned on this side of the mountains.