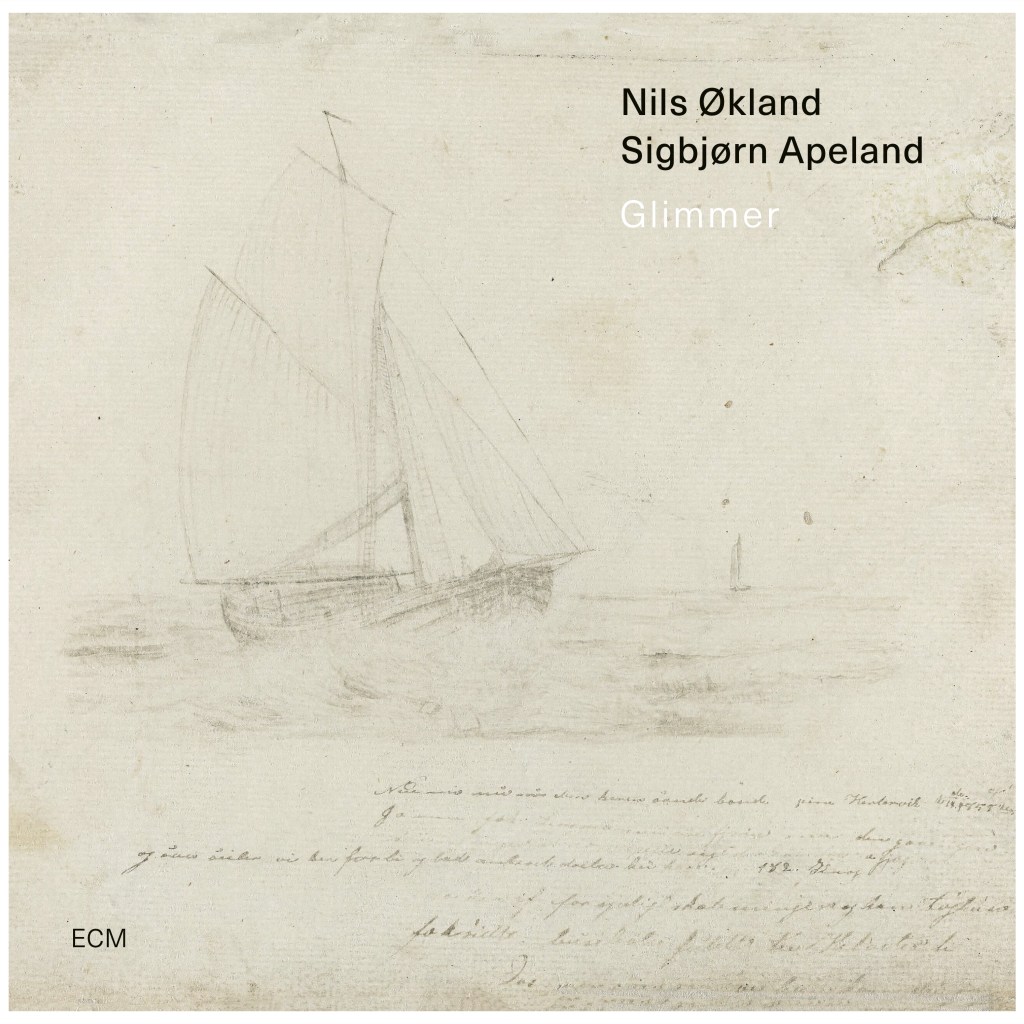

Nils Økland

Sigbjørn Apeland

Glimmer

Nils Økland Hardanger fiddle, violin

Sigbjørn Apeland harmonium

Recorded January and March 2021 at ABC Studio, Etne, Norway

Engineer: Kjetil Illand

Mixed January 2023 at Bavaria Tonstudio, Munich

by Manfred Eicher and Michael Hinreiner (engineer)

Cover drawing: Lars Hertervig, Sailing Boat, 1858

Album produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: June 16, 2023

Representing nearly three decades of collaboration and exploring a repertoire that spans the gamut from traditional to improvised music (if not one and the same), fiddler Nils Økland and harmonium player Sigbjørn Apeland present Glimmer. The program takes inspiration from their native Western Norway, where Apeland has spent years collecting folk songs preserved by local singers. The duo also includes originals inspired by Lars Hertervig (1830-1902), whose drawing graces the album’s cover.

Most of the tunes survive in the living archive of their homeland, starting with “Skynd deg, skynd deg,” the melody of which melts like ice in the first dawn of spring. In this and its successor, “Gråt ikke søte pike,” Økland’s bow is a root plucked from the ground. The fiddle pulses with life beneath it, strands of potential others sprouting from its central branch, while the harmonium is the sunlight giving it sustenance. After this is “Valevåg,” the first of only two by Apeland (the second being the harmonium-only pulse of “Myr”). Dedicated to Norway’s first atonal composer, Fartein Valen (1887-1952), it is a snaking and mysterious piece that evacuates every mold it creates. This serves as a surreal prelude to “O du min Immanuel,” in which moments of far-reaching breadth wield navigational instruments of great intimacy. Such vacillations are what make the album so compelling.

Much of Økland’s writing favors the brief and the introspectional. Whether in the crystalline beauty of the title track or the haunting, rounded tone of “Dempar,” he draws with a potent pen across thickly fibered paper. And in “Rullestadjuvet,” for which he shares credit with Apeland, he brings forth an understated drama. With so much evocation practically dripping from their palette, they render every contour in three dimensions.

Among the traditionals that flesh out this curation, highlights include “Hvor er det godt å lande” for its dreamy splendor, “Se solens skjønne lys og prakt” for its cinematic charge and magical harmonics, and “Nu solen går ned” for reaching farther than it seems two instruments can. All of these are hymns to something, somewhere.

This is one of those special combinations of instruments that belongs in the same category as Inventio or Ojos Negros, resulting in music that leaves its shadow behind as a reminder of where it has yet to roam.