Siegfried A. Fruhauf’s found-footage films are chemical burns on the skin of cinema. What Stefan Grissemann calls the artist’s love of the “raw, handmade, seemingly unfinished” isn’t a retro affectation but an ontological position: the image must not be allowed to settle into complacency.

Film is always in the process of dying, degrading, collapsing, and fraying, yet from this entropy, Fruhauf cultivates an extraordinarily steadfast precision. His sources are organs of a larger body mutating under pressure. Each short feels like an autopsy born of its own fragility. His work reminds us that film is a minor miracle rendered mundane by familiarity, even though its ability to inscribe time should overwhelm us.

This attention to mortality begins immediately in La Sortie (1998), where a primal scene of workers leaving a factory is stretched and compressed until their exit becomes a mechanical tremor. Bodies speed up, slow down, and drone against industrial hums until they dissolve into motion without origin. The message is clear: even the most iconic images cannot hold still. Celluloid labors against its own impermanence.

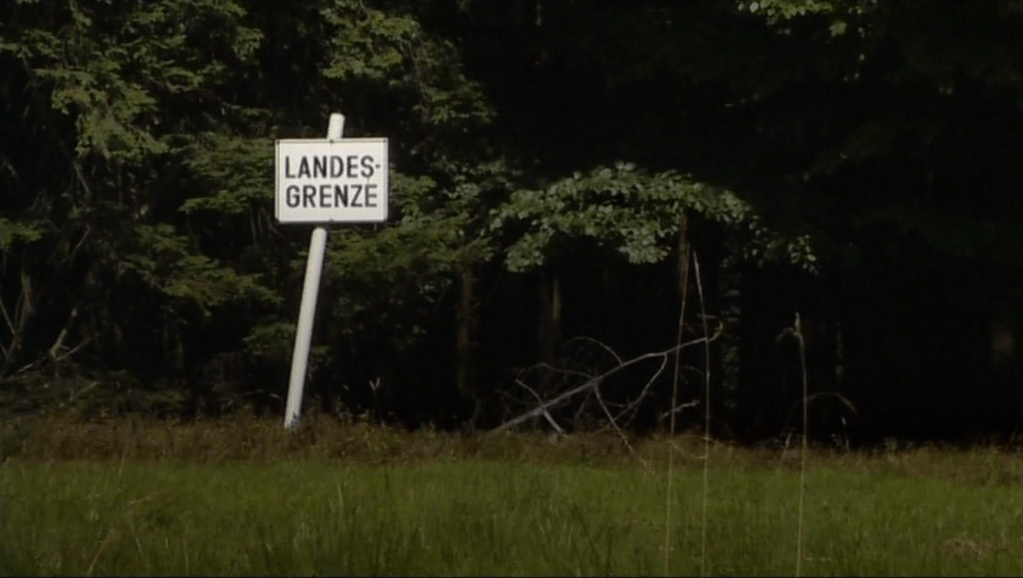

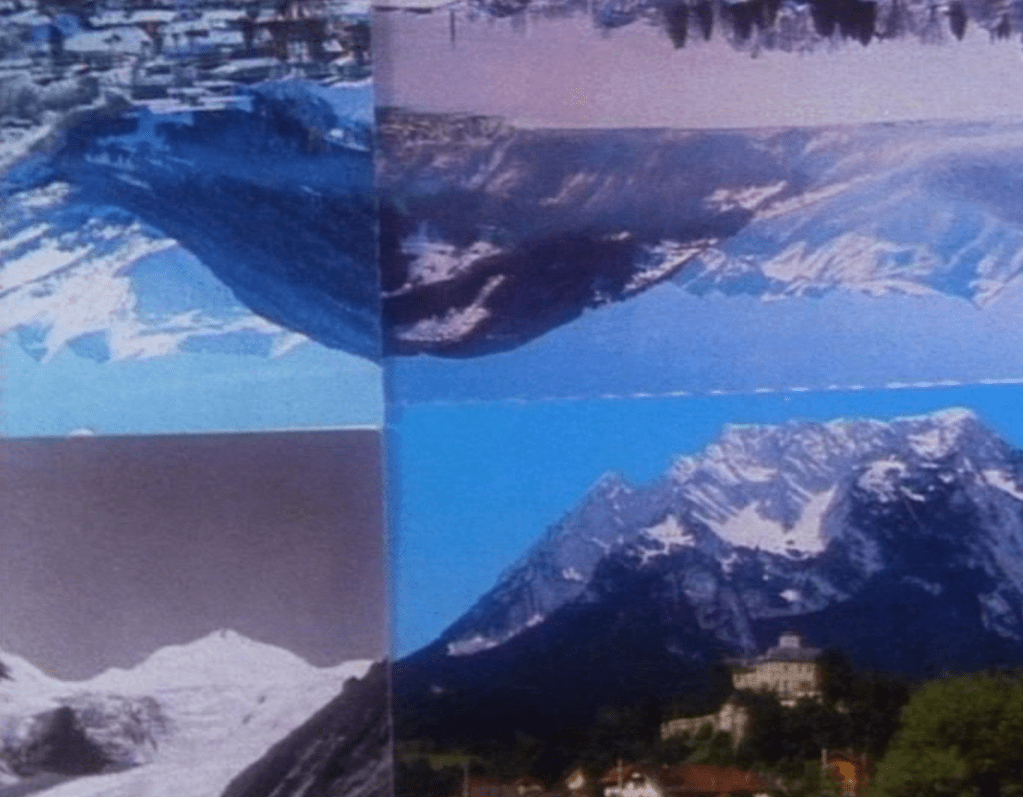

The postcard innocence of Höhenrausch (Mountain Trip, 1999) offers no reprieve. A sequence of Austrian mountain postcards glides past with an artificially cheerful guitar accompaniment. Their pace accelerates until the idyll becomes grotesque, a surplus of images exposing the violence of sentimentality. These snapshots, usually invitations to belonging, reveal themselves as curated illusions once velocity tears away their charm. Fruhauf shows how repetition can uncover the brutality hidden within the familiar.

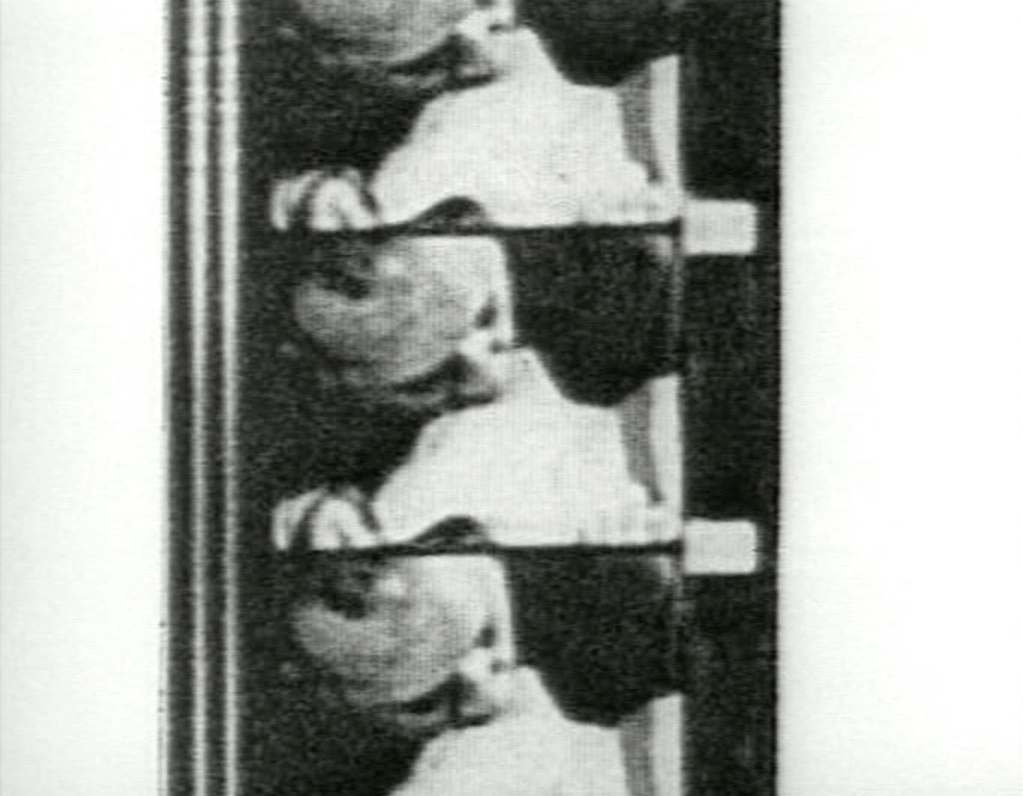

Erotic unease enters the frame in Blow-Up (2000), where an educational film on mouth-to-mouth resuscitation proves uncanny on its own terms. We observe the filmstrip from a distance, listening to distorted breathing as the camera approaches. The woman’s inhalations shift from instructional to suggestive, revealing how fragile intention becomes when context is strained. Fruhauf listens to the footage as a pathologist to the body, waiting for signs of distress that were never meant to be audible.

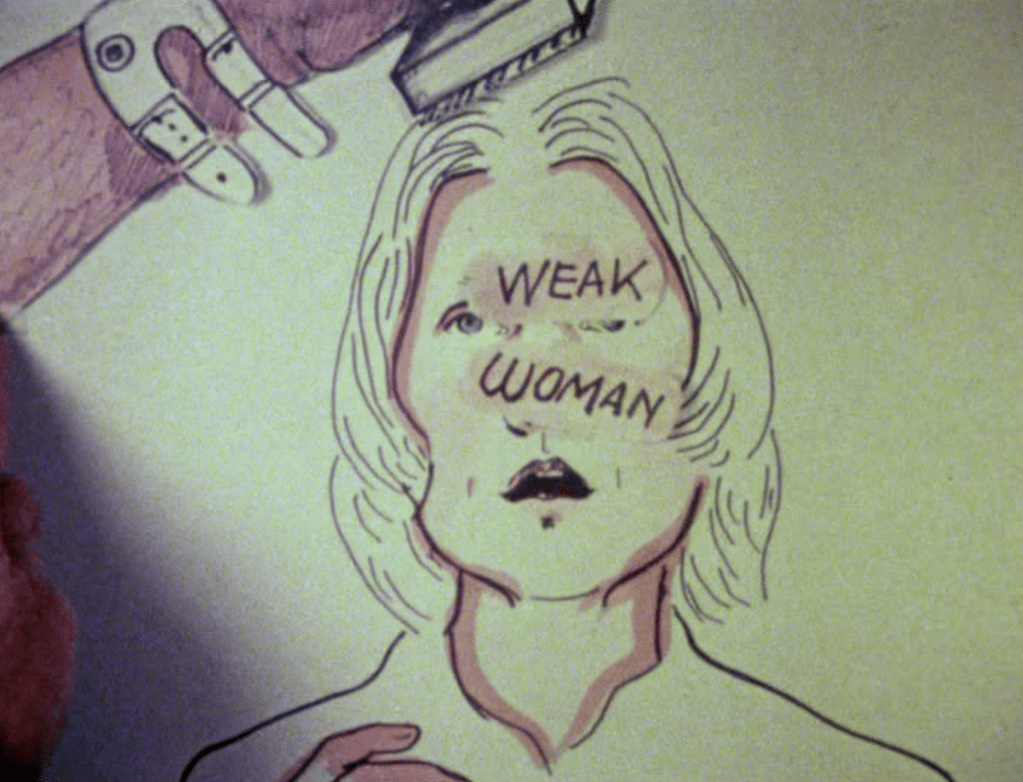

This diagnostic instinct reaches its clearest form in Exposed (2001), one of the collection’s strongest works. A man peers at a woman through a keyhole, a simple voyeuristic setup unraveled by repetition and sound. The woman’s body trembles into abstraction as the distorted breath returns. Desire becomes surveillance, and surveillance becomes a wound. When the woman is finally revealed openly, smoking and unguarded, the image lands as a quiet indictment of the gaze that preceded it.

A shift toward landscape occurs in REALTIME (2002), where a sunrise, tinted green, rises to a pop track stretched into an otherworldly drone. The effect is familiar yet estranged, as if the sun were trying to recall how to rise after forgetting the sequence.

From there, the films plunge into material debris. Structural Filmwaste. Dissolution 1 (2003) arranges discarded darkroom artifacts in dual frames punctuated by digital wipes and unstable white voids. Jürgen Gruber’s electronic score pulses like a remnant of lost memory. The fragments seem determined to form meaning and equally determined to dissolve before doing so. The result is a visual analogue to the temporal disintegrations of William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops, where beauty becomes the residue of decay.

The recursive logic deepens in Mirror Mechanics (2005). A woman wipes a mirror again and again, her reflection fracturing into drifting geometries. The repetition recalls Martin Arnold’s compulsive loops and Peter Tscherkassky’s optical detonations, yet Fruhauf’s tone drifts toward melancholy rather than rupture. Images of the woman floating in water or running along a beach fold into themselves like psychic diagrams. She remains surrounded by a closed circuit of glances, trapped within the mirror’s ongoing self-examination.

This struggle between image and intruder becomes literal in Ground Control (2008), where ants crawl across the frame in patterns that threaten to consume the image entirely. The digital plane pushes back. The surface wrinkles, repels, and kills. The act feels miniature but chilling, a reminder that the image can fight for its life.

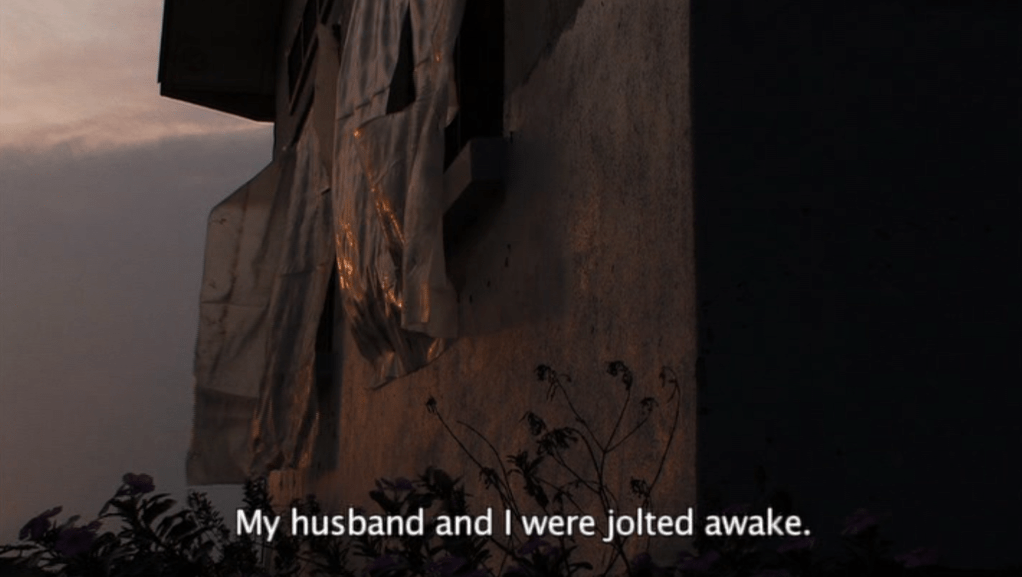

The calm of Night Sweat (2008) is equally deceptive. A treeline at night, slow cinematographic encroachment, then a rare convulsion of lightning accompanied by distorted screams. The moon rises pixelated, then dissolves. The serenity holds only as long as the sky refrains from tearing itself open.

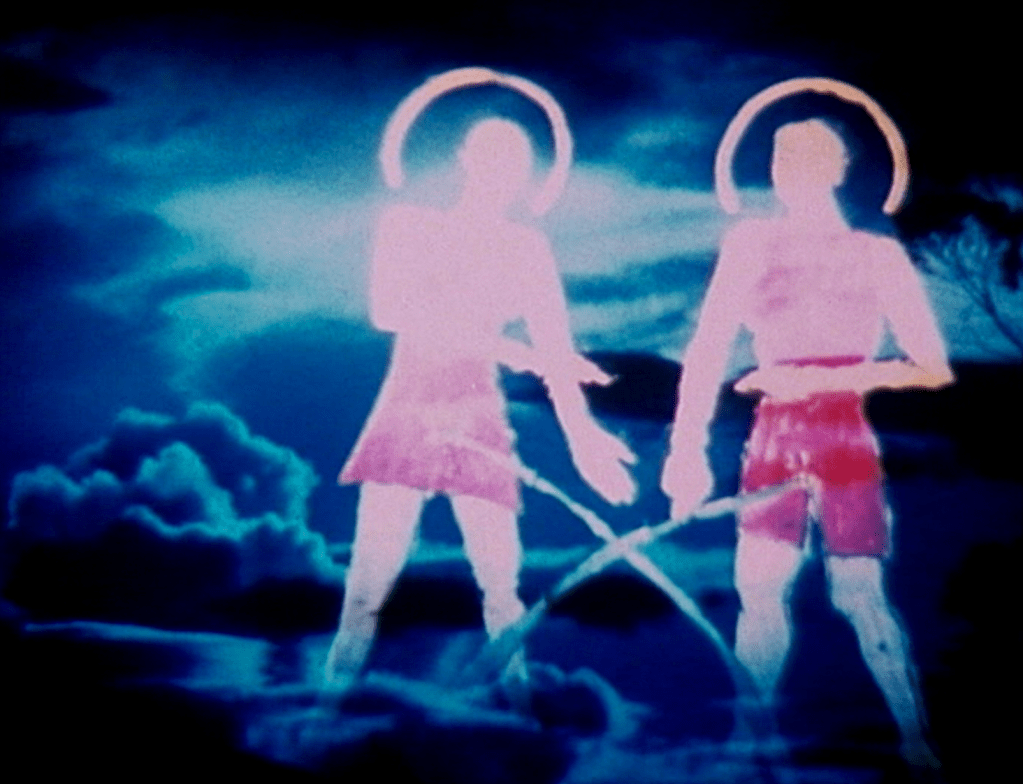

Instability reaches fever pitch in Palmes d’Or (2009), where more than eight hundred Cannes photographs become a rapid negative collage. Architecture flickers into shards, palm trees dematerialize, and the sequence ends in virtual fire. Fruhauf cauterizes the glamour until only a scorched symbol remains. By comparison, Tranquility (2010) feels almost misnamed. Beach and ocean imagery ripple with hints of war, machinery, and parachutes, as if memories of violence haunt the shoreline. The waves embody an undertow of buried histories, their calm a thin surface stretched over turbulence.

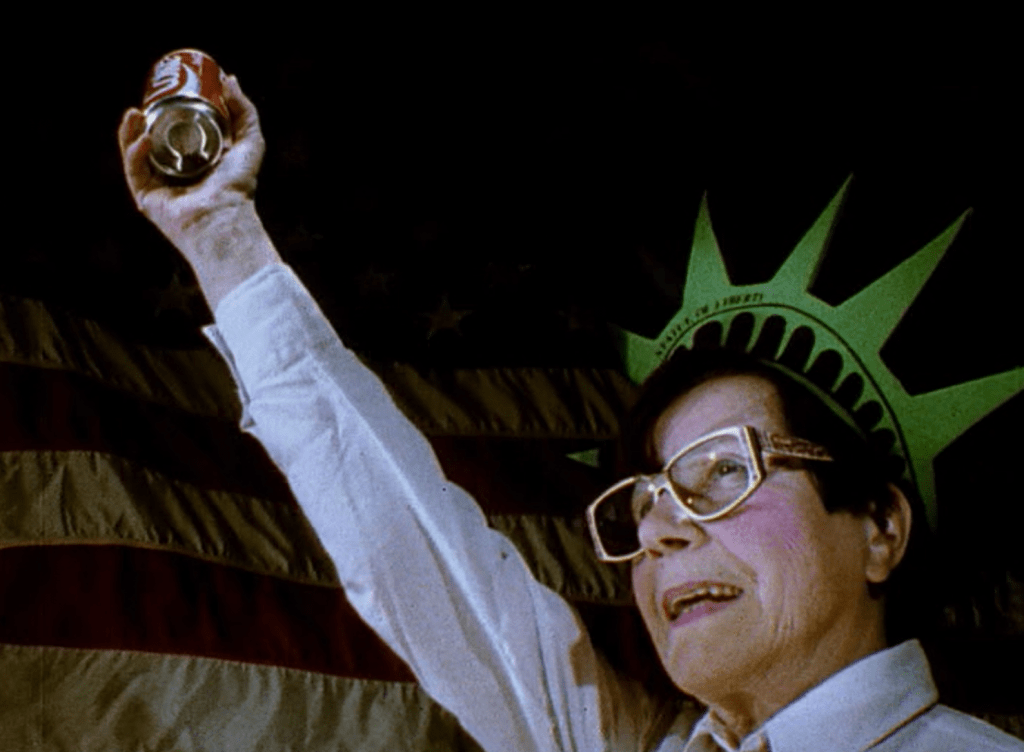

The bonus works extend this reflection on instability. Frontale (2002) stages the impossibility of desire as a man and woman attempt to kiss, only for their identities to double and collide, with car crashes interrupting their union until a shattered windshield marks the moment eros finally arrives. Phantom Ride (2004) transforms an empty train car into a ghost vehicle sliding through night streets before receding into its own absence. Mozart Dissolution (2006) reduces the composer’s silhouette to vibrating graphic traces of Eine kleine Nachtmusik without letting us hear the music itself. A warped LP scratches out the ghost of a melody the likeness can no longer produce.

Cumulatively, this body of work feels like cinema trying to expose its own skeleton, revealing the nerves, scars, and residues that usually remain hidden beneath appearances. Fruhauf scrapes at the emulsion until the surface gives way and the image confesses its condition. What is ultimately found, then, isn’t footage but consciousness in raw, unrefined form.